The biggest single contract in Norwegian history

Norwegian Contractors (NC) and the Aker group had options to build the GBS and topside respectively. Aker’s option included a reservation that the contract would be put out to tender before a final decision. This was the first time since Condeep construction began that the group had to compete in the market on price.

Statoil had made it clear that a tendering process was important for the profitability of the project. It was announced in January 1978 that Norwegian fabricators alone would be invited to tender.

A joint venture between Brown & Root and Norwegian Petroleum Consultants (NPC) had secured the job of engineering management contractor (EMC) as early as 12 November 1976. It was thereby responsible for complete technical design, management of all project work, and the award and management of contracts on behalf of Mobil.

Even before the contract had been signed, Brown & Root/NPC started mobilising staff and launching work on their own account. This activity was suspended after a letter sent by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) on 11 November prompted the Statfjord group to halt all work on Statfjord B.

The EMC received a new assignment to study alternative platform concepts.The joint venture continued to build up a workforce during the spring of 1977, and had put a large operational staff in place by the time the final choice of platform type and design was made at the end of that year.Where the other contracts were concerned, both NC and Aker were short of work and both had planned their operations and dimensioned their workforces on the basis of the Statfjord B contracts.

NC and the GBS

Bygging av betongunderstellet,

Bygging av betongunderstellet,NC was fairly sure that it would finally land the job of building the GBS for Statfjord B. Throughout the process, it was clear that a concrete platform would be built and that this would be the Condeep design owned by NC.The element of uncertainty was provided by the choice of construction site.

NC itself want to use the dry dock at Hinnavågen in Stavanger, but the government signalled that the work should be located for employment reasons at Åndalsnes further north. That was where the TCP2 platform for Frigg had been built.NC won the day, and signed the largest construction contract in Norwegian history until that point on 21 February 1978. To be performed in Stavanger, the job of building the Statfjord B GBS was worth some NOK 800 million.

Topside tussle

Although the contract to fabricate and outfit the B platform’s topside had yet to be awarded, Aker chief executive Carsten H Schanche had highlighted the group’s need for the work even before the type of structure had been determined.

In June 1977, he told Oslo daily Aftenposten that the Stord Verft yard north of Stavanger had no orders from 1978 and that 850-1 150 people would be left without work. He called for the decision on the type of platform to be speeded up, so that the yard could start its preparations. His statements conveyed a certainty that Aker would secure the contract.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten. (1977, 30 June). Stortingsbehandling gir ny Statfjord-forsinkelse.

The government supported Aker’s fight for the job. Faced with a direct question from Aftenposten on whether the group was assured the contract, director general Knut Dæhlin at the Ministry of Industry responded: “Aker undoubtedly expects to [win the contract] after what happened with the first planned B platform. While it is difficult to say how certain this will be in the new circumstances, there is undoubtedly every reason to be fairly confident in that respect”.

Dæhlin thereby expressed the ministry’s attitude on who should get the contract. He continued: “Quite a lot lay in the option Aker obtained at that time. How many contracts Aker secures depends on which concept the Statoil-Mobil group adopts, but work will be available there for the shipyard group in any event.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten. (1977, 30 June). Stortingsbehandling gir ny Statfjord-forsinkelse.

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontraktThe Statfjord licensees were under heavy pressure over the contract from unions, industrial companies and the political leadership in the industry ministry to award the contract to Aker. Stord Verft was convinced that it would win and that the ministry and Statoil would steer the job in its direction for regional policy considerations.

Aker’s optimism rested primarily on the political guidelines which had been adopted. It seemed politically impossible to bypass the group, which ranked as Norway’s largest industrial combine, and risk losing thousands of jobs. A lack of work for Aker would hit not only its own labour force but also a host of sub-contractors.

By November 1977, the Statfjord group was ready to present its plans for Statfjord B. The largest contract in Norwegian history was due to be awarded, the job which would rescue Norway’s shipyards – particularly in the Aker group – from mass redundancies and layoffs.

When the new platform concept was approved by the NPD on 20 December 1977, Aftenposten wrote that it was now clear that Stord Verft would build the topside. It deduced this from a meeting between representatives from Stord local authority, the surrounding Sunnhordland region, the yard’s chief executive, union convenors, and the local and county councils with Reidar Engell Olsen, state secretary (deputy minister) at the industry ministry, and Leif Aune, minister of local government and labour. The purpose had been to brief the two politicians on the seriousness of the position for jobs at Stord.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten. (1977, 20. December). Stord skal bygge B-dekket.

It was understandable that Aker and Stord were sure of victory. Everything written and said in this period was about when the yard could start work, not whether it would get the contract.

A shipbuilding crisis prevailed in Norway as in the rest of the world, and a number of yards were competing. Statoil long wanted to favour Stord Verft, but welcomed open competition.It was at this point that the Kværner group threw itself into the battle for the topside contract, and Oslo daily Dagbladet could reveal on 21 December that it was in the lead. Mobil believed Aker had done a worse job than could be expected with the Statfjord A topside, while Kværner Brug Egersund south of Stavanger had made excellent progress in fabricating the loading buoy for the A platform.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet. (1977, 21 December). Norske industrigiganter kjemper, Kværner leder.

Moss Rosenberg Verft (MRV)

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontraktThe outlook for Kværner shipbuilder MRV’s Rosenberg Verft yard in Stavanger was also uncertain. Like other yards, it had turned its attention from a vessel market in the doldrums to the oil industry.

Rosenberg Verft presented itself to Mobil, Statoil, NPC and NC in the spring of 1977, and signalled great interest in Statfjord B. Initially, it aimed at securing the jobs of producing and installing mechanical outfitting in the cells and shafts of the GBS, and of fabricating process systems for the topside. But the yard also maintained that it had the capacity to build the latter.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 364.

Latticework or steel plates?

While the topside on Statfjord A was constructed of steel plates, the EMC concluded that the B platform should be a latticework structure. That would provide natural ventilation and improve opportunities for escape routes. The latter was important as one of the safety requirements set by the NPD.[REMOVE]Fotnote: As the name implies, latticework is a support system which comprises a framework of braces under tension or compression. It is often used in bridges. The Eiffel Tower is a well-known example. This could create problems for Norwegian yards, since none of them had any experience with such structures in connection with platform construction. Kværner Brug Egersund nevertheless indicated that it would prefer latticework, while Rosenberg Verft was keener on steel plates. So was Stord Verft. The latter had earlier had to relinquish the topside contract for the TCP2 platform because the latticework structure involved proved too difficult.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet. (1977, 21 December). Norske industrigiganter kjemper, Kværner leder.

MRV had been engaged from 1975 in planning and designing a complex gas liquefaction facility for the National Iranian Gas Company. This floating terminal for the production and intermediate storage of liquefied natural gas (LNG) would be built and outfitted at Rosenberg Verft. The gas would be sold to the USA, against strong opposition from environmentalists who claimed that an explosion in an LNG terminal close to densely populated areas would be disastrous. A decision was constantly postponed, and the political position in Iran became more and more unstable during 1978. Kværner finally withdrew from the project and maintained that it would not be able to meet the deadlines and bid price because too much time had elapsed.

Third option

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontraktAnother candidate entered the lists in April 1978. Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted, De Groot Norge and Haugesund Mekaniske Verksted had established a binding collaboration in the oil sector, directed first and foremost at contracts for Statfjord B.This meant there were three contenders in the race – Aker, Kværner/MRV with Rosenberg Verft in Stavanger and the new partnership, which wanted to split the work between Haugesund north of Stavanger and Fredrikstad south-east of Oslo.

These were the competitors Mobil invited to submit tenders. All three had empty order books and risked having to lay off workers without new contracts. The job they were fighting for comprised the fabrication and outfitting of a latticework topside in steel, installation and outfitting modules and steel decks, and commissioning ahead of tow-out of the completed platform.

And the winner is…

As late as August 1978, Dagbladet declared once again that “The Statfjord B topside will be built by the Aker group”.[8] The paper did not explain the specific basis for its assumption but “because of the assessments made so far, it is possible to report today that the Aker group is the strongest candidate to win the topside contract …”.

This was a view Dagbladet shared with many others. Everything appeared to be in place for a Aker to win another major contract. In November, however, the decision which launched Norway’s biggest industrial quarrel of the 1970s was announced. The contract to fabricate the Statfjord B topside had been awarded to Kværner and MRV’s Rosenberg Verft in Stavanger.

Preparations for building this structure began as soon as the contract had been secured. The work was to be split between three different towns.

Half the module support frame (MSF) would be fabricated at Kværner Brug Egersund and the other half at Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted. Rosenberg Verft would install four concrete columns on the seabed outside its yard for the topside to stand on while the two MSF sections were connected and then outfitted. The structure would then be transferred to barges for towing to Vats on the Yrkje Fjord north of Stavanger for mating with the GBS.

Rosenberg Verft would also prefabricate part of the topside components which were to be installed immediately after the sections from Egersund and Fredrikstad arrived in Stavanger.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet. (1978, 28 August). Statfjord B-dekket bygges av Akergruppen. The Kværner bid had been NOK 350-400 million lower than the tender from Aker. But surprise at the decision was expressed from most quarters. More attention was expected to have been paid to regional policy and employment considerations.

A leader in Bergens Tidende levelled sharp criticism at the politicians and Statoil, and questioned how it was possible for the contract to be awarded to a yard in Stavanger when that city was already experiencing a high level of economic activity.

“This has nothing to do with regional policy,” the Bergen daily argued. “So what kind of policy is it?”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1978, October). Kværner-gruppen vant drakampen. and

Bergen Tidende. (1978, October). Statfjord B-katastrofen.

Everyone thought the Statfjord group could not avoid giving the job to Stord Verft, which had invested NOK 100 million in converting from shipbuilding to the petroleum sector precisely with an eye to the Statfjord B topside contract. Aker had gained a clear understanding that the government believed Stord Verft was where the building of offshore installations should be concentrated. And the yard itself maintained that it was the only fabricator with the necessary experience after building the Statfjord A topside.

War breaks out

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontraktCommenting on the decision, Statoil chief executive Arve Johnsen explained that Kværner’s bid was significantly lower than Aker’s and its yard was fully on a par in purely technical terms. It would then have been difficult to give the job to Stord, since that would have been tantamount to subsidising the yard.

He also believed that employment considerations and the future of the Norwegian engineering industry had been taken into account. “But we can’t apply regional policy considerations at a cost of several hundred million kroner.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: VG. (1978, 4 October). Jokeren i spillet om Statfjord. and VG. (1978, 4 October . «Alvorlig feil».

Aker refused to accept defeat, and launched an assault on Statoil and Mobil. The decision was dubbed an industrial scandal. The group was willing to fight for its jobs with everything it had, and much use was made of press releases and statements to the media. Everyone was criticised.

John Sakseide, joint union convenor for the Aker group, told Oslo daily VG: “I think it’s first and foremost the ‘Yankees’ in Mobil who must accept responsibility for the choice that’s now been made. Those fellows are only interested in financial considerations – they don’t give a damn about Norwegian regional policy.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: VG. (1978, 4 October). Jokeren i spillet om Statfjord. and VG. (1978, 4 October . «Alvorlig feil».

A point seldom made in the media was that MRV was in the same difficult position as most other Norwegian yards. Rosenberg Verft was Stavanger’s biggest employer, and substantial cutbacks would have had considerable negative effects even if the city was experiencing development pressures.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1978, 4-20 October). Statfjord B reddet oss fra store vansker.

The Ministry of Petroleum and Energy was established in 11 January 1978. Energy issues had become more controversial, adding to the workload on the industry minister. Bjartmar Gjerde, the current holder of that job, decided that his ministry had to be split up, with petroleum and energy issues hived off. He opted for the job as Norway’s first petroleum and energy minister, while fellow Labour politician Olav Haukvik became industry minister.

Aker’s management and unions made every effort to persuade the government to change the decision. It was speculated that two of the bidders had not been given the opportunity to negotiate on pricing the contract. The union branch convenors in Aker and Stord local council called on the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy to investigate what had happened. Kværner was alleged to have been allowed to modify both technical solution and bid price.

Schanche reacted strongly and claimed that Aker had been treated unfairly.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1978, 6 October). Kontakt uten konkurranse. Had it been given the opportunity to negotiate on price, the group would have felt compelled to make substantial reductions if that was necessary to win the job and thereby prevent extensive redundancies and layoffs. But Aker had received no signals from the client that price discussions would be possible.It eventually emerged that identically worded telexes had been sent to the three bidders on 8 September, during the final phase of the tendering process. Mobil had requested more detailed specifications of certain cost items and reductions of specific amounts. In addition, the operator called on all three to come up with a price and technical solution for a special production method involving the construction of the topside on four concrete pillars.

Kværner had responded that it was prepared to look at its bid once more, and thereby entered into fresh negotiations. Aker’s response was that it has already taken account of possible cost savings in its bid. The latter was framed in such a way that the group could not take account of the client’s request for alternative technical solutions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 368. Aker had stood by its bid, precluding itself from further discussion. So it failed to enter a negotiating position by its own choice. The problem was that the group had not perceived the telex from Mobil as an offer of negotiations. It put its case in a press release:

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt“It has been alleged that the Aker group received signals that such a price reduction should be made but, in that case, these signals were not picked up by the Aker group. On the contrary, the Aker group’s negotiators had formed the impression that price talks would form a natural conclusion to the on-going negotiations on contractual terms and technical parameters.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1978, October). Hevder fortsatt at selskapet ble urettferdig behandlet.

The release also stated that Aker would have been able to reduce its price if it had entered into fresh negotiations. “In order to avoid the need for redundancies/layoffs at the companies affected, the Aker group would have felt compelled to make substantial price reductions.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1978, October). Hevder fortsatt at selskapet ble urettferdig behandlet.

Mobil took the view that it had treated everyone the same. Before the price negotiations in September, the MRV bid had been the highest. Afterwards, it was the lowest.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 368 Furthermore, 400 000 work-hours had been added to Aker’s original bid. The group based its offer on 1.1 million hours, but independent experts had determined that the job needed 1.5 million and Mobil opted for that figure. Aker maintained that the estimate of 1.1 million work-hours built on its experience from similar projects and that it had not been allowed to review the revised estimate, which led to a sharp increase in its bid price.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten. (1978, 25 October). Eksperter øket Akergruppens anbud på Statfjord B- dekket.

The Aker group had undoubtedly felt so convinced that the government would intervene and steer the order to Stord that it had not been as alert as Kværner, and had placed excessive weight on the regional policy arguments. But the latter were not the key considerations for the Statfjord group. Greater weight was given to two other aspects – technical capacity and price.

Aker’s claim of unequal treatment was advanced at a meeting it requested with petroleum and energy minister Bjartmar Gjerde. The group alleged it had not been given the same opportunity as Kværner to discuss price. A meeting also took place between Aker and the bid committee, which the group accused of serious misunderstandings in making its assessment.

Strenuous government efforts had been made to ensure that the topside contract was placed in Norway. But the Labour Party, the Cabinet and the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy all refused to interfere with the bid evaluation process. The most important consideration was that the order went to a Norwegian fabricator, and they would not dictate which domestic company should get the work. That would eliminate the purpose of a free tendering process and free competition. The government could not go that far while it was also pressing for free competition to be adopted in other areas.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet. (1978, October). Vil Gjerde granske Akergruppen?

However, a number of Labour politicians found it hard to swallow that the government fought on the one hand for the regions and on the other allowed Norway’s largest industry contract to go to an area experiencing an economic boom. Gudmund Sørensen, chair of the Labour group on Stord local council, resigned from the party in protest: “What’s happened in this particular case shows that the Labour Party fails to accept the practical consequences of its regional policy programme. When the government refuses to intervene in a matter of such great significance as the Statfjord B case, I can’t belong to the party any more.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A. (2008). Norges evige rikdom : Oljen, gassen og petrokronene. Oslo: Aschehoug: 180.

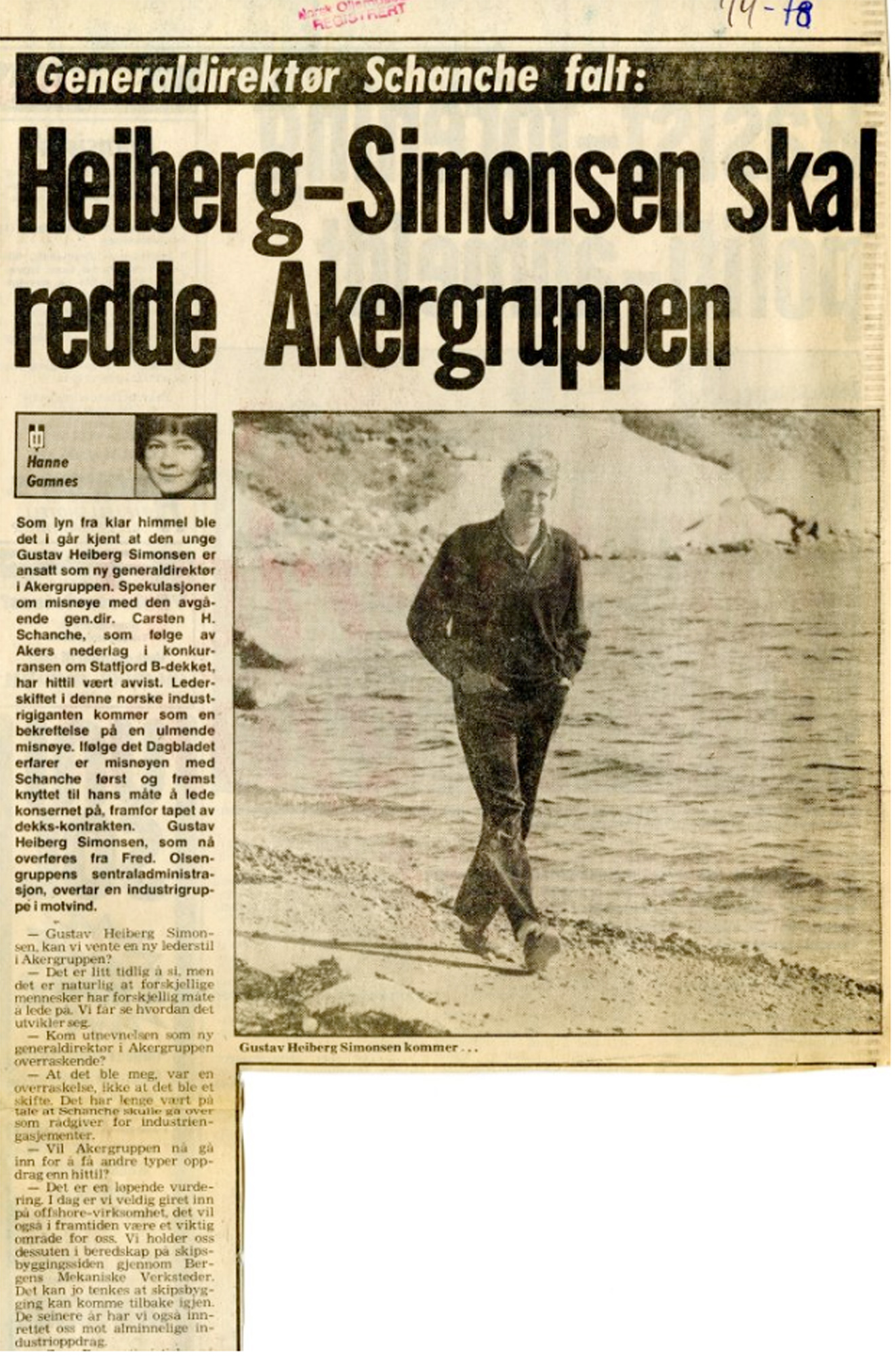

Schanche requested a meeting with Johnsen, where he alleged that he and his company had been treated differently and worse than Kværner. Statoil and Mobil had misunderstood Aker’s bid price. He also questioned whether Johnsen was adequately and fully informed about the whole issue.Johnsen rejected all the Aker chief executive’s claims, and responded that all bidders had been treated identically. Schanche then responded by suggesting that the Statoil boss had received inaccurate or at the very least insufficient information.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet. (1978, 9 October). Kampen om Statfjord B hardner til.

Aker continued to protest, and its criticism of the process became steadily more crass. The fact that two brothers had been involved in the negotiations on either side of the table was highlighted. While H J Frank was chief executive of MRV, his brother Kåre was technical vice president of Statoil. Comments from the chair of Stord council and union officials in Aker suggested that MRV/Kværner had been specially favoured because of these family ties.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Dagbladet. (1978, 9 October). Kampen om Statfjord B hardner til.

But Johnsen made it clear that Mobil had pursued the matter on behalf of the Statfjord group, and that Statoil had participated solely as an observer. To the extent that any decisions had been taken by the state oil company, they were made by him as chief executive.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A. (2008). Norges evige rikdom : Oljen, gassen og petrokronene. Oslo: Aschehoug: 182.

This affair had a sad outcome, in that Kåre Frank resolved to commit suicide on the grounds that he would always have to live with accusations of showing favouritism.The press now began to change its focus from massive support for Aker and Stord.

A number of commentators began to ask whether the Aker management ought not to give up and devote its attention to establishing how the group could lie NOK 350-400 million above the lowest bid. It was seen as a bad loser.Interest shifted from regional policy considerations to greater concern with the technical solutions MRV had come up with to achieve such a big reduction in the price. That could be very valuable for further development of the North Sea.

When Aker claimed after its defeat that it could have reduced its bid substantially, commentators began to ask how that was possible unless it had initially allowed for a good profit margin.

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontrakt

Norgeshistoriens største enkeltkontraktJohnsen supports this perception in his book Norges evige rikdom (Norway’s Eternal Wealth). He reports receiving a visit after the affair from Gustav Heiberg Simonsen, the new chief executive of the Aker group: “He immediately visited me to apologise for Aker’s behaviour. He explained that the group had laid it on with a trowel everywhere in pricing its bid for the B topside.”The largest single industrial contract in Norwegian history until then, worth NOK 1.6 billion, was signed at the Mobil offices in Stavanger at 14.00 on 12 October 1978. This followed a two-day postponement so that the issue could be raised during question time in the Storting (parliament). Mobil did not wish to put the legislators under pressure.

Foreigners, unions and a strikeMechanical outfitting contract for Statfjord B