The final redetermination, 1995 – 98

Redetermining interests in an oil field is a struggle over positions and power, with prestige and money naturally lurking in the background. Each company adopts the standpoint it feels will give it the best return. Keeping its cards close to its chest is also important, because the process can have different outcomes.

More about economy

close

Close

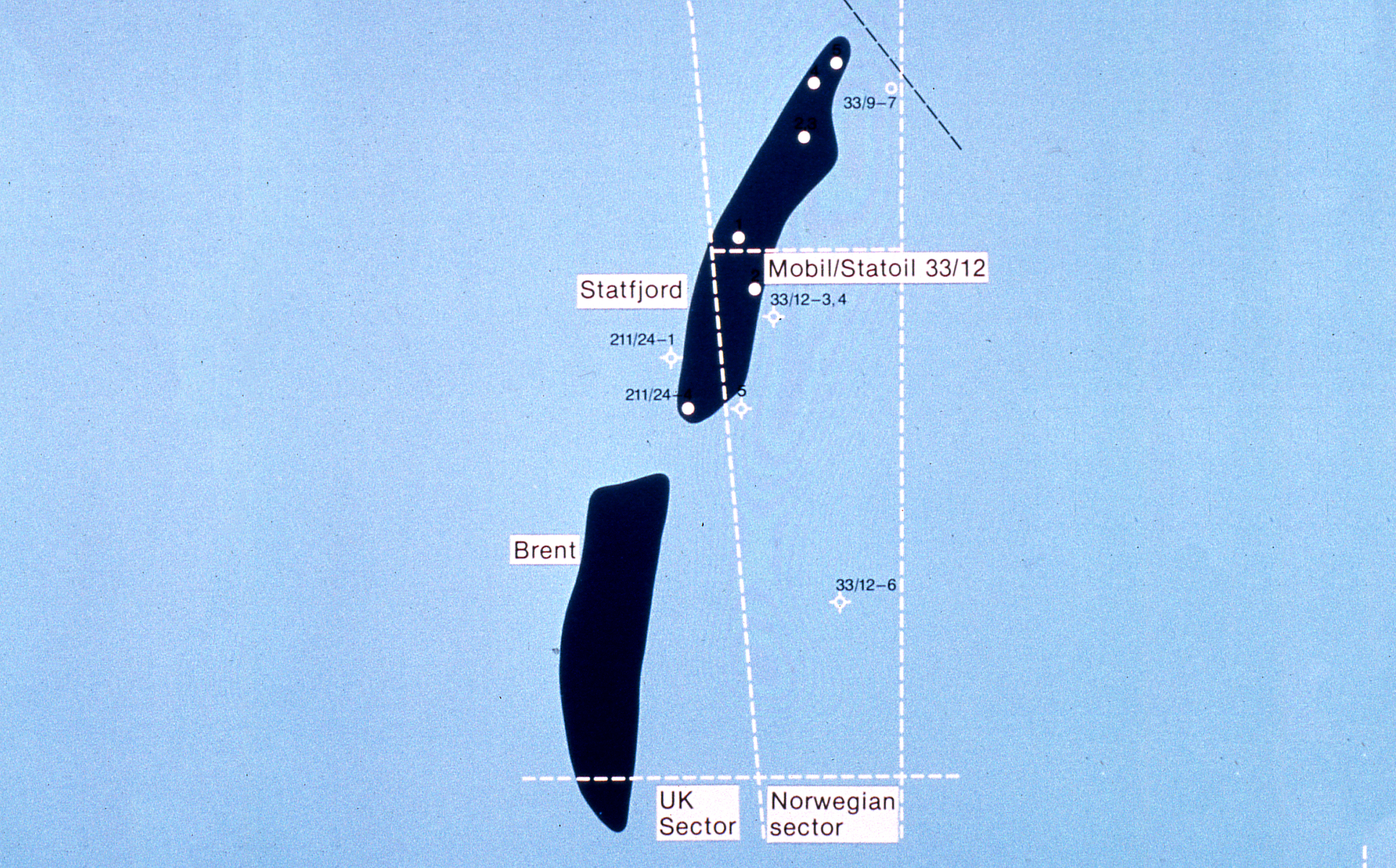

historie, forsidebilde, Hjemmebrent, Den siste redetermineringsprosessen

historie, forsidebilde, Hjemmebrent, Den siste redetermineringsprosessen