The dispute over the loading buoy

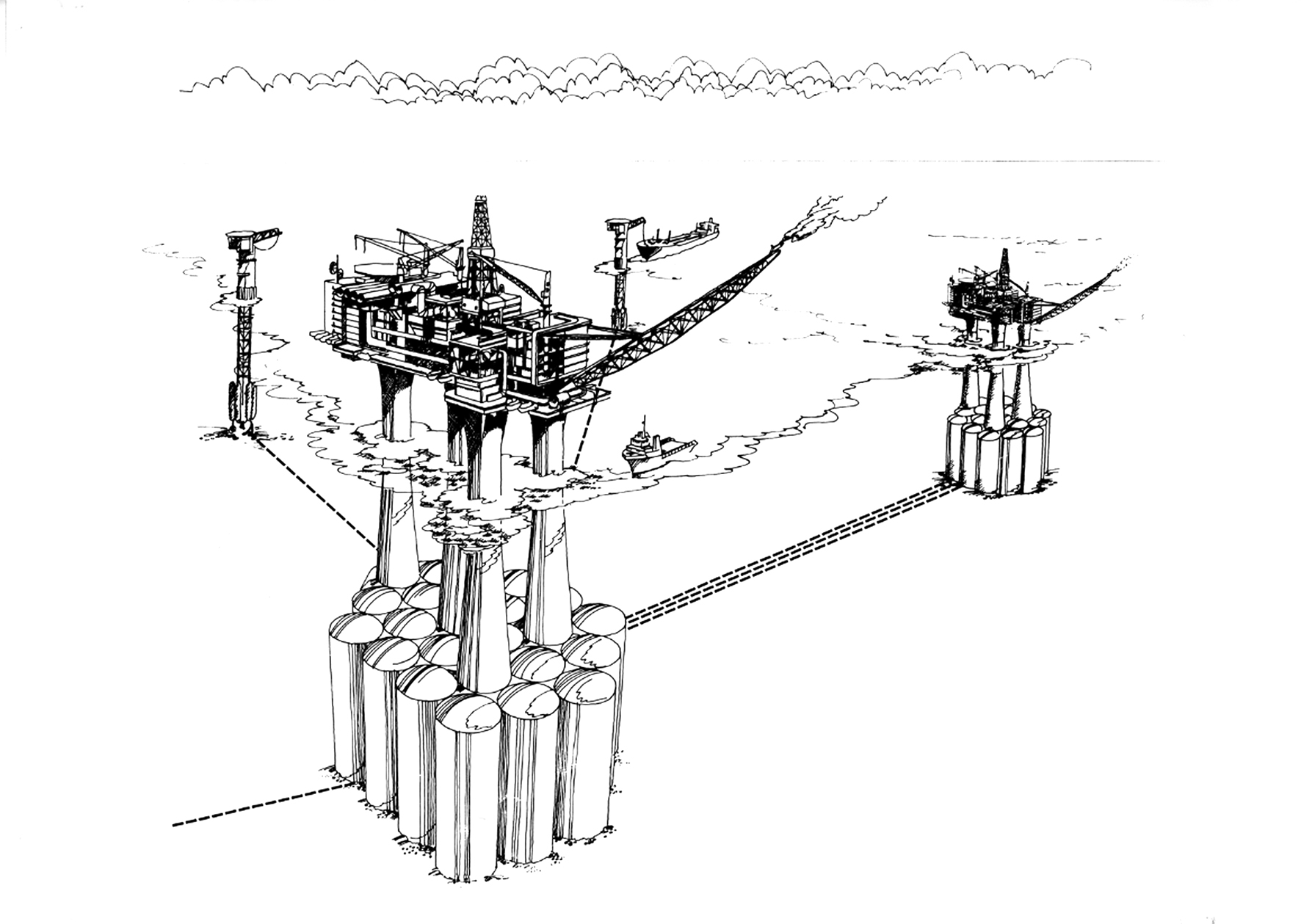

Franco-Dutch SMB had designed the structure as a virtual copy of the Statfjord A unit. The latter had been developed by France’s EMH, which delivered it in cooperation with Norway’s Kværner group.

Invitations to tender were issued in the autumn of 1978 to three potential bidders – Aker, Kværner and Tromsø Fabrications. Aker submitted the cheapest bid and also satisfied the technical requirements.

Based on a fixed price of NOK 220 million, the contract negotiated with operator Mobil detailed the work = to be done. Aker’s various subsidiaries were to carry out everything from planning and procuring materials to fabrication, tow-out and installation.

The contract specified the steel quality to be used and which welding procedures the client required. These strict requirements for metal and welds were intended to guarantee against cracking and fatigue fractures in the buoy. They were never amended.

Striden om lastebøyen,

Striden om lastebøyen,Welding began at Tangen Verft in February 1980. It soon became clear that the yard was unable to meet the contractual quality requirements for weld hardness, and much of the work was rejected.

The media questioned the necessity of the stringent welding standards set by Mobil. Weld hardness was measured at 350 Vickers, with some as high as 400. Mobil’s requirement was a maximum of 325 Vickers. The Vickers scale measures the ability of steel to withstand deformation from external sources, while the carbon content of the steel determines the maximum hardness of the welds.

Many commentators maintained that the requirement had no scientific basis. Oslo business daily Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende claimed that Norwegian welding experts were critical about the use made of hardness figures, and that a weld had to be tailored to the steel which was to be welded.

It also transpired that the steel, which had been purchased from Thyssen Nordsee Werke in Germany, had an excessive carbon content. This made welding difficult. Some speculated that the demands for weld hardness had been tightened, and inspection and testing of the finished welds intensified, in the wake of the Alexander L Kielland flotel disaster.

This had occurred on 27 March of the same year, and one theory about the reason the semi-submersible had lost a support column and overturned in the Norwegian North Sea focused precisely on crack formation owing to metal fatigue. While the standards do not appear to have been tightened, the inspectors could well have been affected by the rig disaster.

Aker halted all work on the loading buoy in July because far too many welds were being rejected. Tangen Verft had to develop new procedures, and these had to be tested. Work continued on the problem throughout the summer holiday without being overcome.

The workforce was then given an extra week’s holiday, which they admittedly had to recover through overtime during the autumn, so that the company had time to develop a method of achieving the correct welds with the steel it was using.

Two factors underlay the welding problems – the deviant steel quality and the expertise of the welders.

Both welders and welding foremen needed to be trained. Aker initiated courses and training for welders, inspections were tightened and the quality improved to some extent.

Striden om lastebøyen,

Striden om lastebøyen,A contributory reason why the welds failed to satisfy the strict standards set by Det Norske Veritas, which carried out the inspections on behalf of Mobil, was that too few ASME G6 welders had been trained. It transpired that the courses launched by Aker were too short and too superficial. Too many welds continued to be rejected.

This marked the start of a bitter dispute between Aker and Tangen Verft on the one hand and Mobil and the Statfjord licensees on the other. The latter took the view that neither the fabricator nor the workers had displayed sufficient willingness to get to grips with the problems which had arisen.

After the Aker group had halted all work on the buoy in the July, however, it submitted a proposed solution which was accepted by Mobil with only minor reservations. This approach involved subjecting the steel to heat treatment.

Tests with the procedure showed that the metal subsequently satisfied the requirements. But the method was expensive, and Aker would not resume work without an assurance that a supplementary bill of NOK 140 million would be paid in addition to the original fixed price of NOK 220 million. It also wanted acceptance that the buoy might be up to a year late.

This was rejected outright by the Statfjord licensees. Aker accordingly felt it could not continue work on the buoy. It was alleged that the demand for an additional payment primarily reflected the fact that Aker had originally submitted too low a bid and now wanted to make up for this.

When it became clear that the contract was under threat, union officials in Aker launched a campaign to influence Statoil and Norwegian public opinion. The Norwegian Union of Iron and Metal Workers (NJMF) vowed at national level that Tangen/Vindholmen would retain the job.

The massive inspection of welders and criticism of weld quality was taken amiss at Tangen Verft, and the workers turned through their elected representatives to the media. They felt they had been portrayed as incompetent and unqualified, while the problem was the steel and the excessively stringent requirements set.

Doubt was cast on Mobil’s good intentions towards Norwegian industry. A campaign was launched to blacken the US company’s name, and it was presented as hostile to Norway’s manufacturers. Iron fixers in Arendal launched a nationwide campaign to identify the experiences of other fabricators with Mobil. The aim was to assemble enough evidence to take the company to court.

The Arendal branch of the NJMF reacted to a number of Mobil’s dispositions during the construction work, and wanted to get the form of the company’s contracts tested legally. It circulated a questionnaire to 10-12 large engineering firms which had fabrication jobs for Mobil, and wanted to tell people about the danger signals transmitted by the operator’s power and influence over their industry.

It seemed incomprehensible to the metal workers that much of Norway’s mechanical engineering industry was struggling with lay-offs and major financial problems when such massive value was being created in the North Sea.

The contract with the Aker group was cancelled and the job transferred to Thyssen Nordsee Werke at Emden in Germany, where the loading buoy was completed. Ironically, this was the same company which had delivered the poor-quality steel to Tangen Verft.

A barge sailed into the Kragerø Fjord on 27 October in order to pick up the finished components and ship them to Germany.

Striden om lastebøyen,

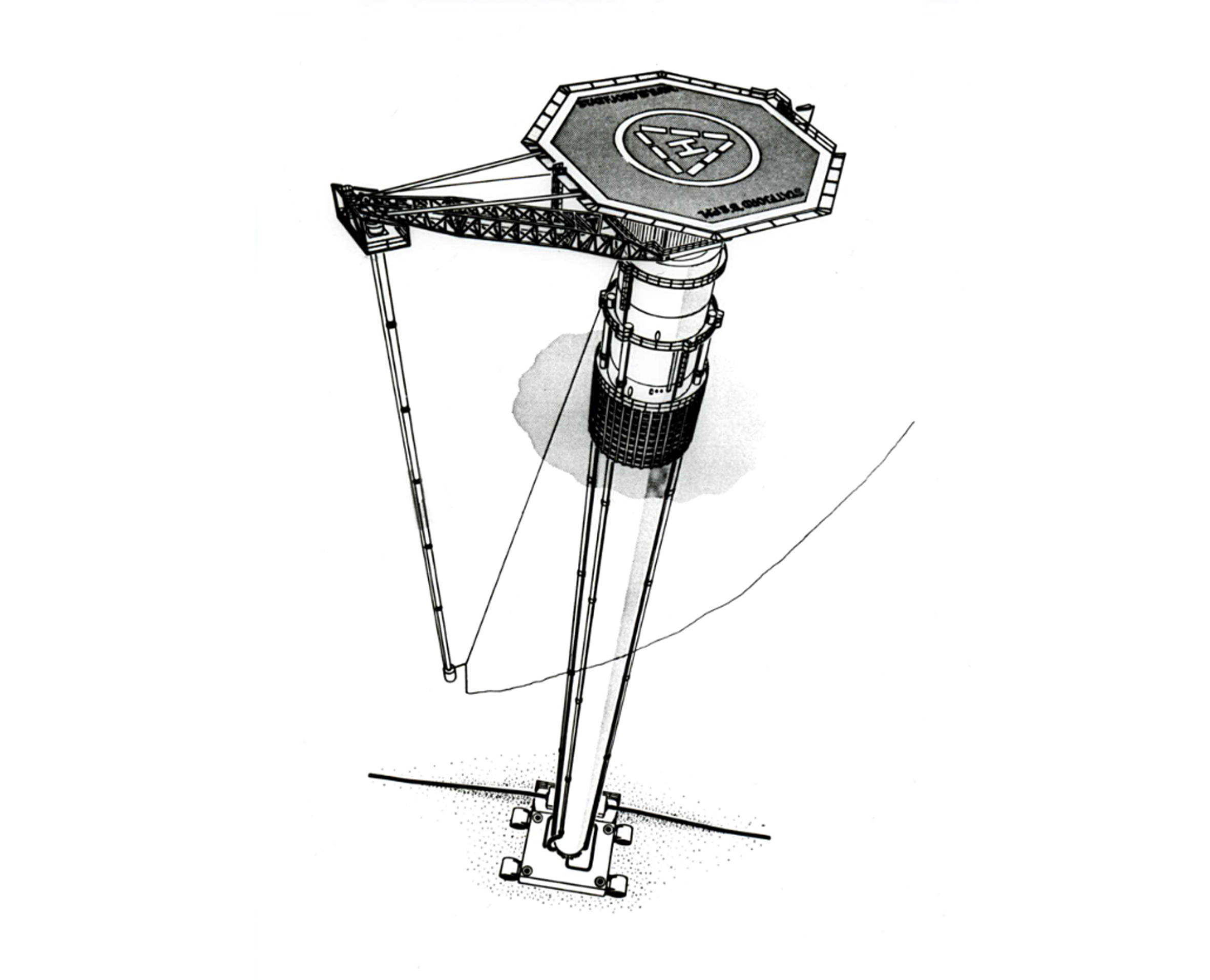

Striden om lastebøyen,When the Statfjord B loading buoy arrived on the field, the A buoy was removed to land for repairs. Flowlines laid between the platforms made it possible to swap between the buoys. Aker presented a compensation claim to the Statfjord licensees because it had lost the contract. It claimed that Mobil had made an error and that the choice of Thyssen would be more expensive than if Aker had been allowed to keep the job.

That claim was very probably correct, but the most important consideration for the Statfjord licensees and Mobil was to obtain a loading buoy which meet the specifications and which was delivered by the deadline.

There was also talk of a counterclaim from the Statfjord licensees against Aker. The former maintained that it could demand compensation of roughly NOK 100 million from the fabrication group because the loading buoy was delayed.

This amount included the cost of laying a flowline from Statfjord B to Statfjord A, so that the loading buoy attached to the latter platform could be used in a transitional phase until the B buoy was in place.

The loading buoy was launched in Hamburg on Friday 30 April 1981 and towed to Aker’s Stord Verft yard north of Stavanger for mating with the topside and base section. It arrived on the field on 1 August.

Sources

Lavik, H., Berge, L., Gooderham, R., & Statfjord-gruppen. (1997). Statfjord : The largest oilfield in the North Sea. Stavanger: Statfjord group.

VG. (1980, 2 October).