A giant mated

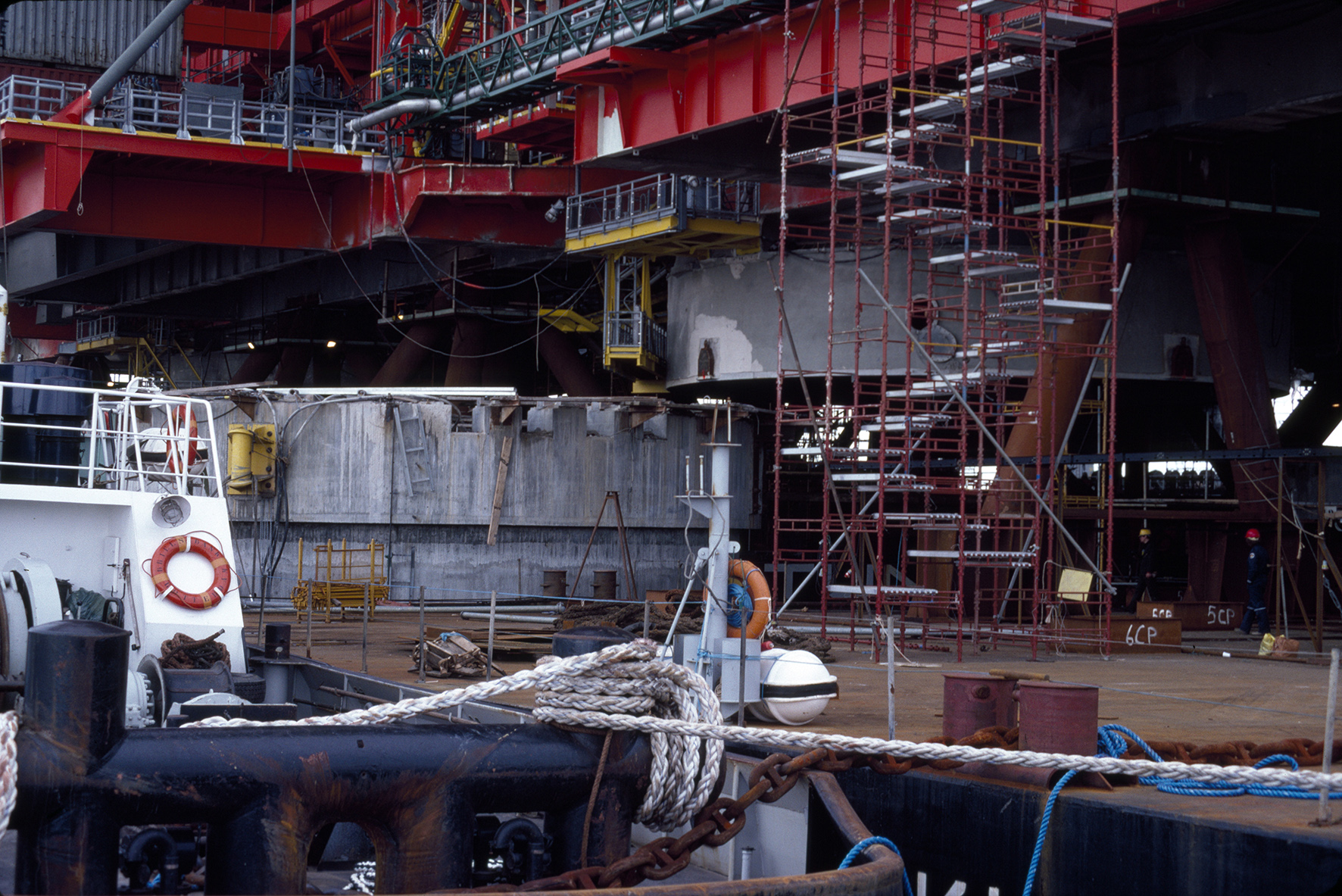

Divers had descended to a depth of 55 metres to burn off four solid chains linking the GBS with the attachment points on land which had held the structure in place since it was floated out to the fjord from the Hinnavågen dry dock in June 1979. Without the chains, only four cables held the giant in place.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil. (1981). nr 2.The tow could begin once these were cut.

b-plattformen, bygging,

b-plattformen, bygging,Nine powerful tugs from three different companies – United Towing in the UK, Germany’s Wijsöller and Dutch Heerema – took a day and a half to move 634 000 tonnes of concrete and ballast north from the Gands Fjord off Stavanger to the Yrkje Fjord in Vindafjord local authority.

Ranked as the heaviest in the world up to that time, the tow maintained an average speed of 1.5 knots. Three tugs pulled from the front, two pushed from behind, two lay alongside the GBS to act as side thrusters, and the last two lay aft of the tow and functioned as brakes when necessary.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1981, 14. februar).

A total of 100 000 horsepower was deployed.

The voyage headed along the shipping route through the islands north of Stavanger. North of Finnøy, it turned eastwards and rounded Ombo to the south and east before crossing the Nedstrand Fjord and entering the Sandeid Fjord. The route then curved west again into the narrow Yrkje Fjord.

With a deep draught of 62 metres, the tow demanded a minimum water depth of 70 metres. This was no problem along the shipping channel. But the passage between the Brattholmen and Teistholmene islands at the mouth of the Gands Fjord was only 280 metres wide, and the tow’s width was 135 metres ¬– giving a clearance on either side of just 70 metres.

Great caution was needed there. Taking a tow through a narrow channel calls for short towing lines. Propeller backwash will then be so strong when it encounters the GBS that the structure becomes impossible to steer.

Norwegian Contractors (NC) had experienced this itself on the first attempt to tow the Statfjord A GBS. The solution was to use two powerful tugs to push the structure through the channel.

The route was chosen on the basis of detailed investigations. For two years, currents had been measured, meteorological statistics studied and tests conducted in the ship model tank in Trondheim.

Surveyor Bloms Oppmåling had installed a number of theodolites along the route to take sightings from land as a safety precaution. Combined with acoustic electronics on the GBS, it was used to ensure that the tow stuck exactly to the planned route, that nothing surprising occurred, and that the precise position was known at all times. Two systems with independent power supplies ensured that one would remain operational if the other went wrong.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1981, 20. februar).

The tow was implemented without problems, and the GBS was moored on arrival in the Yrkje Fjord while awaiting the arrival of the topside it was to be mated with.

One of the world’s heaviest lifts

En gigant settes sammen,

En gigant settes sammen,A month later, the topside left Moss Rosenberg Verft’s Rosenberg Verft yard in Stavanger on its way to the Yrkje Fjord. Four large barges had been manoeuvred into place at the yard with the capacity required to lift the structure from the four concrete pillars on which it was built.

Two of the barges were placed outside these supports, while the other two – Goliat 8 and 9 – were placed one atop the other and guided under the centre of the topside. Pumping ballast water out of the barges raised them until they had lifted the topside a couple of centimetres. That was sufficient to free it from the columns in preparation for the tow through the fjords to the mating site in the Yrkje Fjord.

It was not possible to pull the deck free with the tugs, so steel cables were attached to the pillars. As these were winched in, the barges carrying the topside were pulled cautiously forward.

Together with Swedish towing specialist Neptun, NC was responsible for the lift-off at Rosenberg Verft and the tow to Vats. This ranked as the first time a complete factory with an eight-storey living quarters was towed as a single package. The voyage began in the afternoon of 24 March.

The draught of the tow was only 12 metres, so the water depth in the fjords presented no problems for the topside either. Between Spolen and Klovningene just outside Stavanger, however, the passage was only about 300 metres wide, which offered very little leeway.

After maintaining an average speed of three knots, the topside reached the Yrkje Fjord safely in the early morning of Wednesday 25 March. A troublesome east wind meant it had to wait on weather at the mouth of the fjord.

Mating GBS and topside called for almost complete calm, but a weather window opened between two anti-cyclones on the Friday morning, and the operation could begin.

One plus one equals big

En gigant settes sammen,

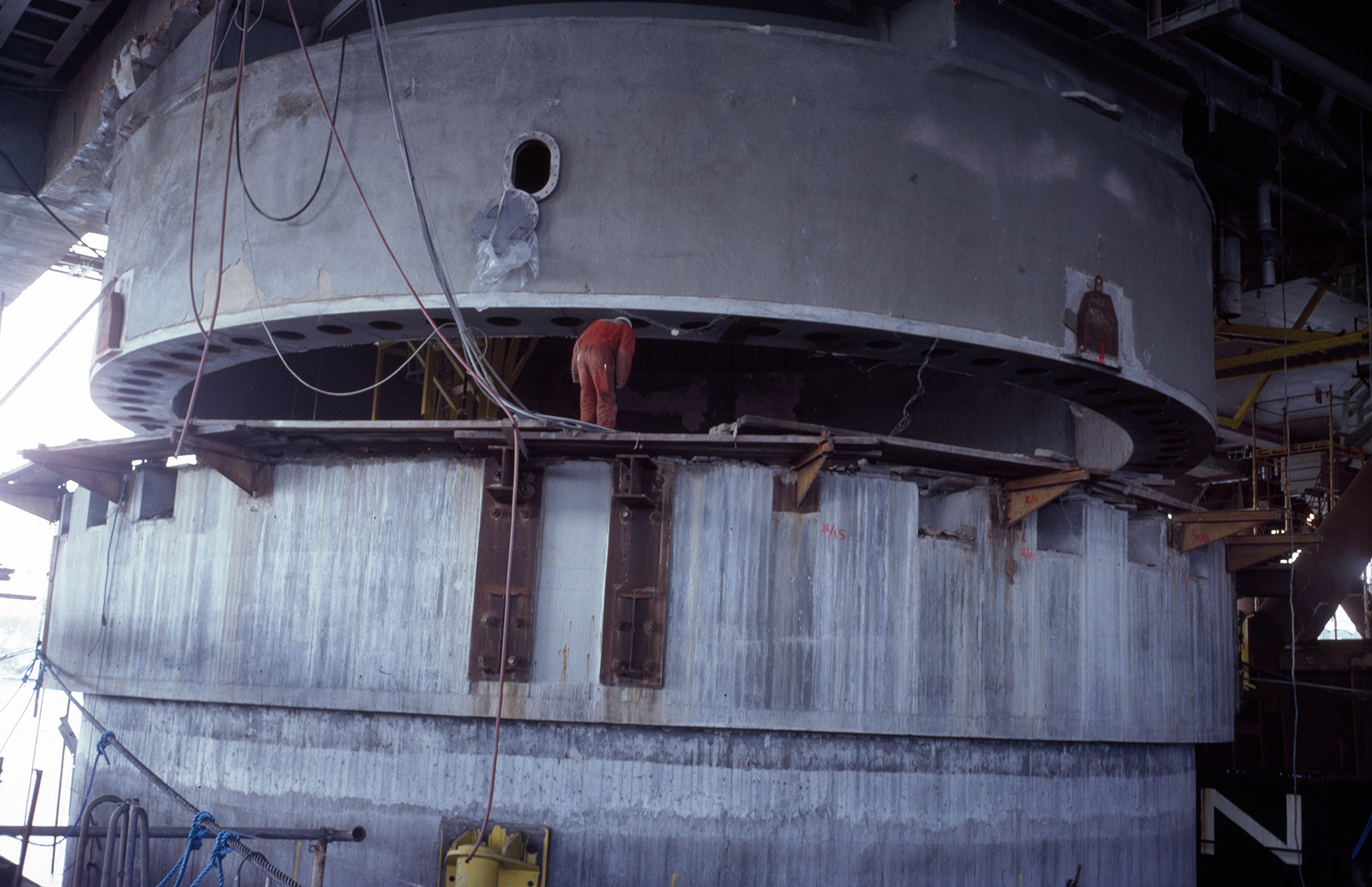

En gigant settes sammen,After the tugs had manoeuvred the topside over the GBS shafts, cables and winches attached to the latter took over. They repeated the process carried out at Rosenberg Verft, but in reverse. Fine adjustments were made with the aid of jacks, which pushed the topside horizontally.

Virtually no tolerance was permitted when mating the topside and GBS. The circular shafts had to engage with four steel rings beneath the topside within an allowable variation of a few millimetres. It took 100 people on the barges and tugs to bring the deck in line with the steel rings and with the 104 bolts, each as thick as a man’s arm, which were to tie them to the concrete structure.

The GBS was moored throughout the operation, but floating in the water. According to Bjørn Vidar Lerøen, then a journalist with Bergens Tidende, the concrete structure lay like a set of submerged lemonade bottle with only the lips for attaching the crown cap showing.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1981, 26. mars).

Only 6.5 metres of the 177-metre-high unit was visible above the water.

En gigant settes sammen,

En gigant settes sammen,Once the topside had been correctly positioned, water was pumped out of the GBS ballast tanks so that it slowly rose and eventually lifted the whole topside off the barges and onto the shafts.

The whole operation was an application of Archimedes’ Principle – if the weight of a submerged vessel is reduced, it will rise in the water. In this case, the submerged vessel was a concrete giant with a displacement of 550 000 tonnes. That meant a lot of water had to be removed from the concrete cells, and it took three days before the topside had reached its planned height of 50 metres above the sea surface.

This represented one of the most impressive marine operations the world had so far seen. To achieve the smoothest possible transfer of weight from the barges to the GBS, the former were also ballasted down with water and slowly sank lower in the sea as the concrete structure rose.

The topside was positioned with an accuracy of five millimetres. Its full weight had been transferred by Sunday 29 March and the barges could be pulled away. Eight people staffed the control room in the GBS’s utility shaft and controlled the ballast pumps in the structure, 160 metres below sea level.

Almost offshore

Once the deck had been mated with the GBS, work could begin on hooking up cables, piping and all the other systems tying together the two components.

The work of commissioning the platform had been well planned. Phase one, the initial hook-up, was handled by 150 people NC had ready in Vats. After that, Rosenberg Verft and Mobil took over the work site and some 1 000 new workers arrived to hook up countless more modules and components – both between the GBS shafts and the topside, and between various parts of the latter.

A new, comfortable work camp with beds for 462 people had been installed on the slopes above the quay area at Raudnes. A number of barges supporting temporary accommodation had also been towed into the fjord and moored.

In addition, a couple of hundred workers could be accommodated in the living quarters on the actual platform. Temporary offices, canteen and sauna had been established.

NC had built a new quay, and a daily ferry service to and from Stavanger was in operation. The boat from Rosenberg Verft left every morning at 08.00 to transport workers and visitors to the construction site. This trip took 90 minutes.

High and low voltage power lines had been laid to the construction site, and a new sewage system was installed with a treatment plant. A subscriber trunk dialling phone service was provided, although Vindafjord was the only local authority in Rogaland without STD at that time. NC had also helped to finance a new road from Åmosen to Raudnes.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1981, 21.februar).

The labour force observed an offshore tour system, and lived at Vats while at work. They were looked after well ¬– the food from Bergenske Catering became known for its “offshore” standard.

A dedicated welfare secretary ensured that leisure activities were many and varied. These included outings to see the flowers in the Hardanger Fjord, boat hire for angling and film shows twice a week. Outings to nearby Haugesund were organised at the weekend – either to and from on the same day, or with an overnight stay from Saturday to Sunday. Various sporting activities were pursued, the library was well stocked and distance learning courses could be taken.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1981, 18. mars).

Among those who won contracts for the commissioning of Statfjord B was Alvide Berge from Sinnes in Sirdal, popularly known as Shipowner Tina. She had six boats at Vats, used to ferry personnel to and from the platform out in the fjord. In addition, her Oanes car ferry served as headquarters for the operations management.

Berge had started her little company as early as the construction of the Statfjord A GBS in the Gands Fjord, providing boats which shuttled between Hinnavågen and the concrete structure with everything from plastic buckets to passengers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1981, 28. mars).

The work in the Yrkje Fjord took four months, and one of the last structures to be installed was the flare stack. This 155-metre-long unit was lifted into place in a single operation by the world’s largest crane ship, Hermod, which arrived in June.

b-plattformen, forsidebilde, Jeg døper deg Statfjord B,

b-plattformen, forsidebilde, Jeg døper deg Statfjord B,On 17 June 1981, Statfjord B was named by lady sponsor Agnes Rettedal. She was the wife of Arne Rettedal, mayor of Stavanger at the time. Thirteen days later, the platform set off on its last voyage – and more world records were broken.