The original plan – Statfjord B

Plans called for the platform to be installed on the field in 1979. Arriving at this solution was a long and difficult process, involving many stakeholders.

Stage one – preliminary and final plans

Den første planen – Statfjord B

Den første planen – Statfjord BThe Norwegian licensees[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil 50 per cent, Mobil Exploration Norway Inc 15 per cent, Norske Conoco 10 per cent, Esso Exploration and Production Norway Inc 10 per cent, A/S Norske Shell 10 per cent, Saga Petroleum a/s 1.875 per cent, Amoco Petroleum Company 1.042 per cent, Amerada Petroleum Corporation of Norway 1.042 per cent, Texas Eastern Norwegian Inc 1.042 per cent. established a licence 037 committee, which functioned as an informal decision-making body. In September 1976, the Statfjord licensees submitted a preliminary field development plan to the Ministry of Industry. This proposed a three-stage approach.

Phase I was Statfjord A, an integrated production, drilling and quarters (PDQ) platform with a daily capacity of 300 000 barrels. This Condeep structure would be placed centrally on the field.

The field development plan also discussed further stages. It found that the reservoir could be drained most efficiently with three production platforms, and proposed that at least two additional structures be built after phase I.

These proposals were accepted in principle by the ministry on 4 November 1974. But it requested a more detailed plan for the first phase, Statfjord A. This was submitted by operator Mobil on 18 February 1975.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 2 : Utbyggingsprosjektene på norsk sokkel (Vol. 2). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]: 139.

By then, casting the concrete GBS for the A platform was already well under way. Mobil had awarded a contract for the GBS to Norwegian Contractors (NC) in October 1974, before the ministry had commented on the proposed plans. While work on Statfjord A was starting up, Mobil began to draw up the full field development plan. This was submitted to the ministry in January 1976 and formed the basis for White Paper no 90 (1975-1976).[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 2 : Utbyggingsprosjektene på norsk sokkel (Vol. 2). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]: 196.

Statfjord was long thought to be part of Britain’s Brent field. However, it transpired that Statfjord was actually the discovery which extended into the UK North Sea and block 211 with Conoco North Sea Inc as operator.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 2 : Utbyggingsprosjektene på norsk sokkel (Vol. 2). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]: 138. Licensees in UK block P211 were Conoco Ltd 33.333 per cent, Gulf Oil (Great Britain) Ltd 16.666 per cent, Gulf (UK)Investments Ltd 16.666 per cent, and the British National Oil Corporation (BNOC) 33.333 per cent.

Stortingsvedtak om Statfjord B og C, historie, Den første planen – Statfjord B

Stortingsvedtak om Statfjord B og C, historie, Den første planen – Statfjord BIn order to establish the size of the field and its division between the two national continental shelves, an initial informal meeting was held between the British and Norwegian licensees. The key issue was to agree a mutual exchange of well and seismic data. An agreement on this was signed in May 1975.

At the same meeting, the licensees’ committee was established as the highest authority for the unitisation work. This body was an extension of the licence 037 committee, where the British licensees were admitted as observers but without a vote. Conoco North Sea Inc acted as coordinator for the British group.

The same meeting decided that Statfjord B should be built as a Condeep with four shafts and a production capacity of 300 000 barrels of oil per producing day. Preliminary work was initiated on that basis.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 2 : Utbyggingsprosjektene på norsk sokkel (Vol. 2). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]: 138.

First of all, the matter had to go through the Storting (parliament). The Ministry of Industry had submitted White Paper no 90 (1975-1976) concerning the full field development plan for Statfjord on the basis of the application submitted by Mobil on 5 January. This secured a majority in the Storting. Labour, the Conservatives and the Christian Democrats supported the government, while the Liberals maintained that account should be taken of employment conditions when placing orders for Statfjord B and that the GBS should accordingly be built at Åndalsnes rather than in Stavanger as planned. The Socialist Left was the only party which had reservations about developing the field.

This reflected its doubts about the expansion of offshore operations. The party proposed that Statfjord production should not exceed 15 million tonnes per annum, and also noted that specific plans for the creation of possible industrial activity in relation to full development of the field had not been submitted.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status. (1976). no 10.

A clear majority nevertheless voted to allow the Statfjord licensees to continue with their plans for three integrated PDQ platforms, each with a daily capacity of 300 000 barrels. The schedule was tight, with Statfjord B due to be towed out in the summer of 1979.[REMOVE]Fotnote: White Paper (Report to the Storting) no 90 (1975-76) On the development and landing of petroleum from the Statfjord field and on a gas-gathering pipeline. Ministry of Industry.

On the following day, 17 June 1976, the licensees held a meeting to establish the Statfjord Unit Operating Committee (SUOC) as their highest decision-making authority. An interim unitisation agreement was signed, which thereby gave the British licensees a vote. Voting rights were allocated in accordance with the percentage interest held by each of the 13 partners.Including the British meant that the licence shares had to be recalculated. Before unitisation, Statoil had held 50 per cent of the Norwegian share of Statfjord. This was now reduced to 44.4424 per cent. Since a valid decision by the SUOC required at least 70 per cent support, however, Statoil retained a blocking vote.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 2 : Utbyggingsprosjektene på norsk sokkel (Vol. 2). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]: 139.

Apart from the unitisation agreement, the most important items on the agenda were to secure acceptance for continuing with the plans for a platform with a capacity of 300 000 barrels per day, order a Condeep and select the engineering management contractor (EMC) to handle design and project leadership.

NPC – a Norwegian option

While work on the formal approval continued, the operator initiated its preparations for building Statfjord B. The first job was to identify possible EMCs. The planned platform ranked as the largest Norwegian industrial project until then, and forces in industry and government wanted to prevent project assignments being awarded outside the country.

On Statfjord A, the bulk of the engineering work had gone to foreign contractors. The main problem was that no Norwegian company was big enough to undertake such a job, and possible contenders also lacked expertise in planning large processing facilities.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Engeland, S. (1995). Ingeniørfabrikk På Norsk : Oppbygginga Av Norsk Petroleumsrelatert Engineeringkompetanse, 154: 33. The three largest industrial groups in Norway – Kværner, Aker and Kongsberg Våpenfabrikk (KV) – met in the spring of 1975 to discuss a collaboration, but failed to agree on its organisation. They nevertheless succeeded in organising a meeting with Statoil on opportunities for winning contracts on Statfjord B.

Statoil was interested in a Norwegian constellation, and wanted this in preference to one of the large international companies. It also gave clear signals that it was willing to look not only at engineering costs, but would also give weight to the positive effects which a Norwegian contractor could have for choosing domestic suppliers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Engeland, S. (1995). Ingeniørfabrikk På Norsk : Oppbygginga Av Norsk Petroleumsrelatert Engineeringkompetanse, 154: 36.

The goal had to be to replace Britain’s Matthew Hall Engineering (MHE) in the next project. During the meeting, Statoil emphasised that resources in Norway were small, and that there was only room for one large Norwegian company. The three industrial combines had to involve more partners, not least with an eye to regional considerations. A joint venture would need to have Statfjord B as its primary goal, but Statoil also made it clear that it would be able to utilise such a partnership in its own later projects.

These suggestions from Statoil were extremely positive, but great disagreement continued to prevail between Kværner, Aker and KV over how a possible collaboration should be organised. From Statoil’s perspective, the three needed to form a joint venture if they were to have chance of winning the Statfjord B contract. It wanted the partnership to be based in Stavanger, but that view failed to win support and Norwegian Petroleum Consultants (NPC) was established at Aker’s offices in Oslo.

The three companies eventually reached agreement. Seven other Norwegian companies – Elkem, Årdal og Sundal Verk, Electro Union, Norconsult, Dyno, Hafslund and Norsk Jernverk – were invited to participate in the new joint venture. The 10 partners would own 10 per cent each, thereby ensuring that none of the three largest would become too dominant and giving the new company an independent image.

According to the business purpose clause for NPC, “the company’s purpose will be to pursue independent consultancy activities – including project management for planning, building and operation of facilities related to oil and gas”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Engeland, S. (1995). Ingeniørfabrikk På Norsk : Oppbygginga Av Norsk Petroleumsrelatert Engineeringkompetanse, 154: 51. Agreement on establishing NPC. The basis had now been laid for national participation in the planning of future petroleum projects, an activity which had previously been reserved for foreign industrial giants.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. )1976).

NPC’s management committee appointed a working party for Statfjord B in November 1975. The joint venture was clearly going to win the contract, but needed a foreign partner to share the work on a 50-50 basis.

Mobil wanted Brown & Root, but Statoil felt that the US contractor had too much of a stake in delivering equipment and preferred Bechtel. While the latter admittedly had limited offshore experience, it could point to long involvement on land with a particular weight in nuclear engineering.

It was to transpire that Mobil had a dispute going on with Bechtel elsewhere in the world, which may have contributed to its opposition to this company. But Statoil was not aware of that at the time.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Engeland, S. (1995). Ingeniørfabrikk På Norsk : Oppbygginga Av Norsk Petroleumsrelatert Engineeringkompetanse, 154: 60. In order to reach agreement, three candidates were invited to tender in open competition for a joint venture with NPC covering the contract for overall project management and engineering services. The invitation was issued on 12 February 1976 to Brown & Root (UK) Ltd, Bechtel International Ltd and Foster Wheeler Offshore Ltd.

Brown & Root + Aker = Brownaker, forsidebilde, a-plattformen, Brownaker etablert, Den første planen – Statfjord B

Brown & Root + Aker = Brownaker, forsidebilde, a-plattformen, Brownaker etablert, Den første planen – Statfjord BMobil got its way. Brown & Root won the job after a hard tussle in the Statfjord group. NPC and Brown & Root agreed to share functions and work between their offices in Oslo and London. Sceptical about NPC and worried about coordination problems between the two cities, Mobil demanded that the US partner should have the lead role. The operator also suspected that NPC would be unable to secure sufficient staff and that its office facilities would be unsatisfactory.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Engeland, S. (1995). Ingeniørfabrikk På Norsk : Oppbygginga Av Norsk Petroleumsrelatert Engineeringkompetanse, 154: 64.

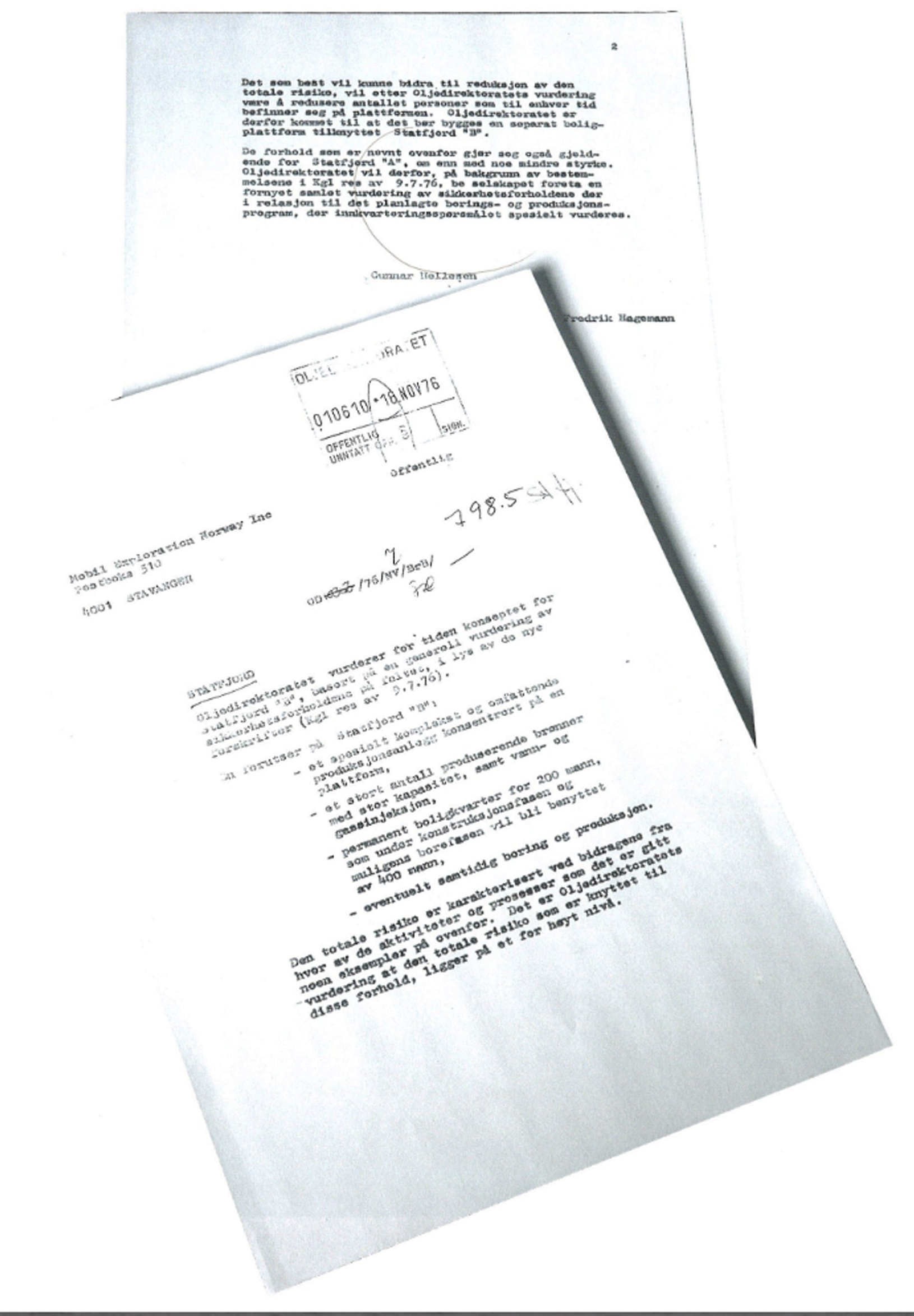

Negotiations began with Mobil in October and the contract was signed after much toing and froing. NPC earned its first revenues on 13-14 November. The letter from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) which changed everything arrived on 15 November.

NC and Aker

The two other key contracts which had to be negotiated were construction of the GBS and fabrication and outfitting of the topside. Strong pressure was being exerted on the Statfjord group by the unions, industrial companies and the political leadership at the Ministry of Industry to award these jobs to NC and the Aker group respectively, without going out to tender.

Statoil also wanted this solution, but it was rejected by operator Mobil. The latter was keen to use Norwegian suppliers, but opposed the monopoly position Aker had built up as an offshore supplier.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 357. NC and Aker had earlier entered into a collaboration agreement which committed any company choosing to order a Condeep to allow Aker to build the topside and handle the mating job. That gave the customer little opportunity to check Aker’s prices against the market.

The cooperation deal had worked as long as both NC and Aker had delivered on time and to budget. But experience with the Statfjord A topside, where Aker’s Stord Verft yard was seriously behind schedule and did not look likely to deliver at the agreed price, did not tempt Mobil to repeat the process. The operator preferred Kværner for the job.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1976). no 7

Mobil accordingly stuck to its position that the topside contract had to be put out to tender, and was supported by the other foreign companies. Statoil also remained adamant that the contracts should be awarded to NC and Aker without competition.

The political leadership at the ministry became directly involved in the issue. Both it and Statoil emphasised that Aker’s employment position was more difficult than Kværner’s, and that an Aker topside was the only possible solution in political terms. Because the crisis in the Norwegian shipbuilding industry was deepening and the outlook for jobs was getting worse, a political desire existed to get started on building Statfjord B as quickly as possible. State secretary (deputy minister) Lars Uno Thulin at the industry ministry called a meeting where he advised the Statfjord group to place the construction orders with NC and Aker.

This political pressure was to no avail. Mobil insisted on a tendering process. It was happy enough to use a Condeep solution, but wanted Aker to face competition.

The Statfjord licensees agreed in the summer of 1976 to adopt Mobil’s approach. The SUOC decided on 31 August that negotiations should be initiated with NC on building the GBS, while Aker had to accept competition. But the latter was confident that Statoil and the ministry would ensure that Stord secured the topside job.A new element was now introduced.

Against the opposition of Britain’s state-owned BNOC, which had a 3.7 per cent interest, the licensees agreed to exercise an option with the Aker group. This contained a clause that the topside should be put out to tender before an order could be placed. The tendering process also involved yards outside Norway, and a decision was to be taken on purely commercial grounds. Although the British interests were not large, BNOC made its presence felt in the SUOC and took every opportunity to press the case for UK industry. But it was politically impossible for the Norwegian government to allow this contract to go abroad.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1976). no. 8

A discussion also took place over the construction site for the GBS. The options were Rauma, Åndalsnes and Stavanger. The industry ministry deployed strong regional policy and employment arguments, and maintained that jobs were most needed in Åndalsnes. But NC wanted to remain in Stavanger, where it had close links with the city’s oil community.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1976). no. 3 The industry ministry issued a press release on 10 September 1976. It was originally due to have been published by the Statfjord group, but the British licensees opposed that plan. This document stated:

“The Statfjord group has resolved to initiate contract negotiations with Norwegian Contractors aimed at ordering a Condeep platform … The Statfjord group has also authorised the operator (Mobil) to enter into an option agreement with the Aker group aimed at fabricating the topside for this platform. However, a final decision will be taken later after bids have been obtained …“

The concrete structure will be built in Stavanger. The four-shaft design will make it possible to tow the platform fully equipped out to the field. In that way, the platform with topside structure can be completed in sheltered inshore waters to a lower cost than would have been the case if the work had to be done out in the North Sea.

“The Statfjord group has also resolved to initiate contract negotiations with a new company consisting of Norwegian Petroleum Consultants and Brown & Root concerning engineering services, technical procurement and construction supervision during the building of Statfjord B.”

Shell says no

On 16 June 1976, three months after NPC plus Brown & Root had been offered the contract, the Storting approved the full field development plan. An interim unitisation agreement was signed on the following day at the first official meeting of the SUOC.

This meeting was also intended to approve the construction of Statfjord B as a platform with a capacity of 300 000 barrel per producing day, the ordering of a Condeep and the choice of NPC and Brown & Root as main contractor.

The plans failed to secure a majority. Instead, Norske Shell questioned whether committing to another giant concrete platform was the right approach. It moved a proposal for two platforms with daily capacities of 150 000 barrels. This would allow production to start more quickly. Shell’s experience with Brent D in the UK sector suggested it would be cheaper, and the licence could save up to NOK 200 million.

This plan was received with a certain amount of understanding by many of the partners, but was unwelcome to the industry ministry and Statoil. Mobil and Statoil both opposed studying the proposal, in the case of the operator because it would lead to delays. But these two companies did not jointly command more than 70 per cent of the votes. It was accordingly resolved that the advantages and disadvantages offered by platforms with daily capacities of 150 000 and 300 000 barrels respectively would be studied. A report would be completed by August.

When the SUOC met again on 31 August, the original development plan was approved unanimously. A four-shaft Condeep would be ordered with a production capacity of 300 000 barrels per day. Shell admittedly requested that its objections be minuted.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 1 : Sammenfatning av utviklingen, vurderinger og anbefalinger (Vol. 1). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]: 206. There was also a majority for awarding the EMC job to a joint venture between NPC and Brown & Root.

Then came the letter from the NPD which changed all the plans.

Brevet, Den første planen – Statfjord B

Brevet, Den første planen – Statfjord B