The occupational health service in a historical perspective

He was given a part-time job in May 1976, at a time when Mobil was recruiting personnel – mostly foreigners and particularly Americans – to fill senior posts. His first job was accordingly to check the health of these US citizens and their families.

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,Jørgensen had trained as a psychiatrist and was with the psychiatric department at Stavanger Hospital when he had his first contact with the oil industry in 1975 through the duty doctor arrangement.

A keen amateur diver, he had acquired substantial expertise in hyperbaric (diving) medicine together with consultant Tor Nome, who later became company medical officer for Phillips Petroleum Company AS. His interest in the oil industry was sparked by this work, and he became relevant for Mobil.

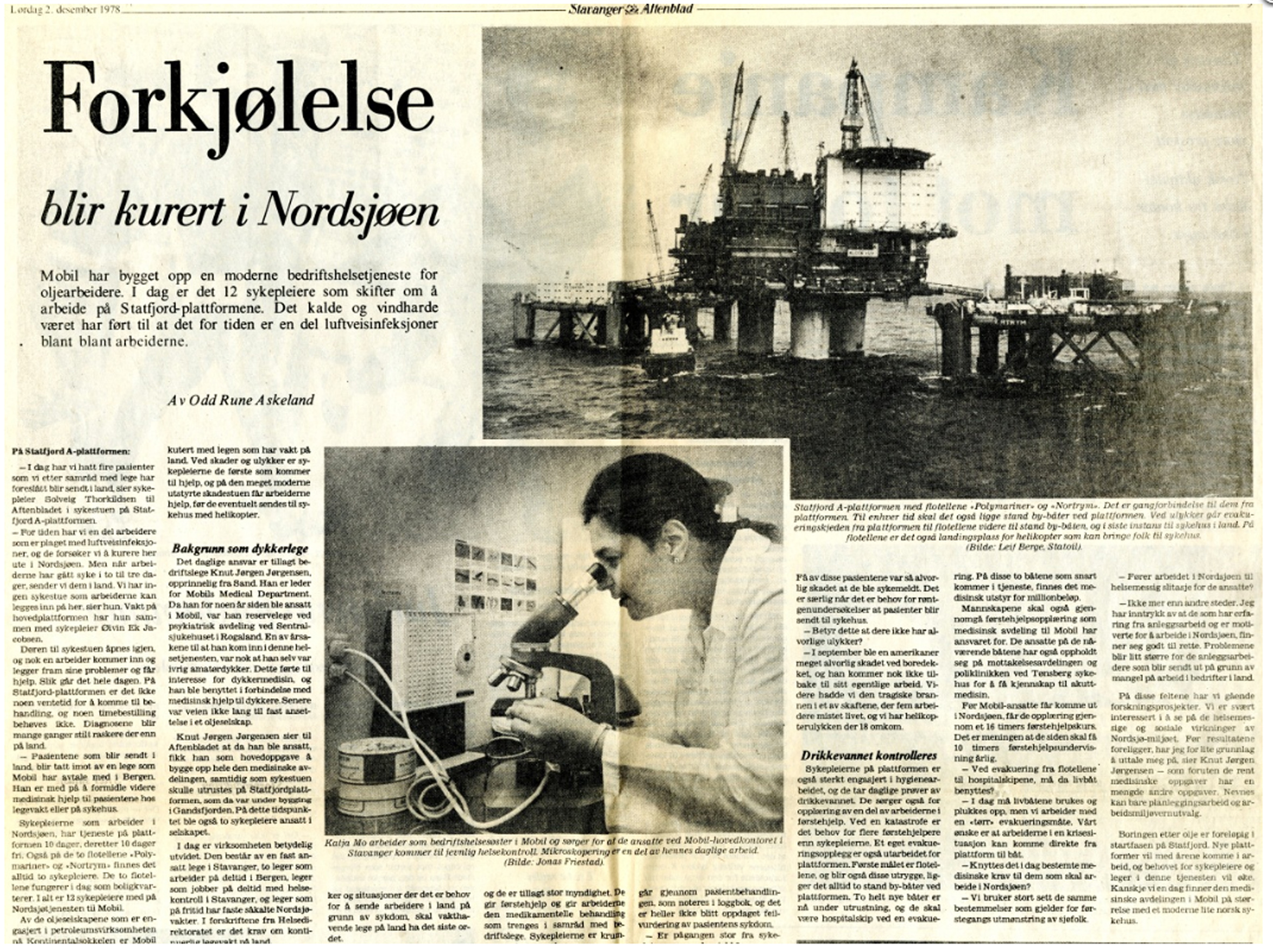

An occupational health service (OHS) for an offshore operator differs from one on land. It must serve not only the company’s own employees, but also everyone else working on the field in question – regardless of their employer.

Jørgensen never had a typical working day in Mobil. The OHS had five principal tasks:

- routine health checks of Mobil’s own personnel

- emergency response medicine

- disaster preparedness, with training of auxiliary personnel as well as organising the medical side and collaboration with public health personnel on land[REMOVE]Fotnote: The department took time to put this into place and to achieve a constructive and efficient collaboration with the civil defence organisation and rescue services. Statfjord B was built with a helicopter hangar, and had a search and rescue (SAR) machine stationed permanently there from the start. See the separate article on this service.

- occupational hygiene, occupational medicine, environmental factors and preventive work

- research[REMOVE]Fotnote: This was an important and highly interesting aspect. Together with doctor Odd H Hellesøy and the New York health service, Mobil initiated a research project as early as 1980 into the social and socio-medical consequences of the North Sea oil industry. Mobil Explorer, May 1979.

[3] Interview with Knut Jørgen Jørgensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 29 April 2011.

Expansion

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,While health checks were being conducted, Mobil was also building up its medical department in Stavanger. A growing number of people were recruited by the company, and the medical officer acquired his own office in the city’s DSD building. He also appointed the first two nurses.

Being able to position health personnel permanently on the platforms as soon as they were in place on the field was important. But views differed in the Statfjord project over requirements for medical personnel.

The logistics manager maintained, for instance, that it would be sufficient to have a radio operator who knew first aid, and could not understand the necessity for nursing staff.

However, Jørgensen stuck to his guns and insisted on nurses. He got his way. It could sometimes be tough to get foreigners to understand Norwegian culture and requirements.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Knut Jørgen Jørgensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 29 April 2011.

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,The OHS expanded rapidly. By 1978, the medical department comprised, in addition to Jørgensen, two part-time doctors in Bergen, part-time doctors doing health checks in Stavanger and duty doctors for the North Sea working on a fixed rota. In addition came a company nurse and medical secretary employed by Mobil at its Stavanger office.

The secretary was particularly useful during the commissioning phase for Statfjord A, when hundreds of Spanish-speaking workers arrived. Jørgensen had recruited Marit Ytterbø, who had been the secretary for the senior consultant in the psychiatric department. She spoke Spanish, and could assist as interpreter.

A total of 12 nurses worked on Statfjord A. As both Statfjord B and C arrived on the field and came on stream, a system of duty doctors in Bergen and a medical office in Stavanger was no longer sufficient.

Duty doctors in Bergen

obil’s OHS centre at Kokstad near Flesland airport opened on 10 March 1982 to serve the Statfjord field and employees in the Bergen area. In addition to regular company medical officer services, this facility was to cover a number of functions.

Its staff were to treat sick or injured employees, organise preventive health services such as hearing protection, manage and assist the offshore nurses, and lead first-aid and other health training.

In addition, the centre would store health data and administer the offshore health service, as well as managing medical reports within the OHS and for the authorities. Jørgensen’s office remained in Stavanger, but he worked regular hours at the Kokstad centre a couple of times a week.

Medical equipment

Outfitting Statfjord with medical equipment was a demanding business. The platform had been designed in London, and Jørgensen started work while it was still under construction. One of his jobs was to provide advice and guidance on the planning and construction of new workplaces.

Space and equipment were required if an OHS was to be built up offshore, and this had not been given priority in the Statfjord A project. Jørgensen and his staff devoted much time and effort to securing acceptance of the need for adequate OHS facilities.

The plans only allowed for a small sick bay, which certainly failed to satisfy the medical service. So the first job for Jørgensen after building up a sound first-aid and emergency response organisation was to join forces with the nurses to plan the equipment, instruments and furnishing they needed offshore.

This experience could then be transferred to the planning phase for Statfjord B and C, where medical facilities were incorporated from the start.

In addition to shortage of space for the OHS, Statfjord A presented major difficulties in evacuating personnel. Jørgensen had to devote much time and effort to convincing the management that safe evacuation was important.

The lifts in the service shaft where too small to accommodate stretchers, for example, and manoeuvring the latter along narrow corridors with many sharp turns took much time and effort in other places.

A single stretcher was one thing, but the question was what would happen in the event of a disaster with a lot of patients. Jørgensen maintained that a broad stair should be constructed on the outside and a proper basket with space for at least two stretchers installed in the shaft.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Jørgensen’s archive 1979. He got the basket, but the external evacuation stairs have still not appeared.

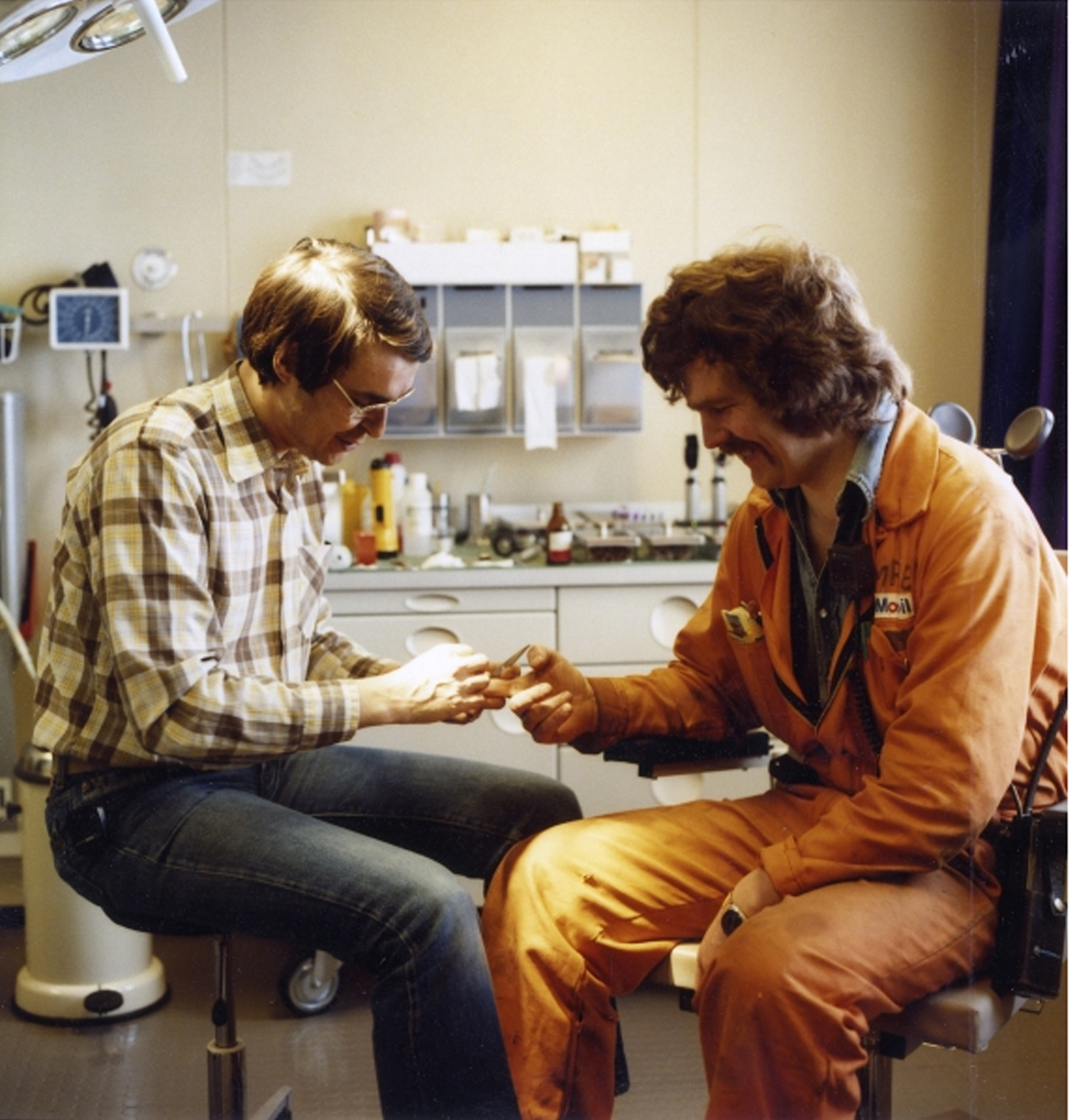

Nurse for 1 400

After Statfjord A had been towed out and the long offshore construction phase began, up to 1 400 people worked there at times. These were divided between the platform and two flotels linked to it by bridges.

This many people necessarily meant that the OHS had plenty to do. Four nurses served on Statfjord during the period, one on the day shift and one at night on the platform, and one on each of the flotels. To start with, there were 2.5 people per nursing post, but this was quickly expanded to three. By 1979, a total of 12 nurses were working on field. They worked a tour rota of 10 days on and 10 off, and wielded great authority.

Labour-intensive early years

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,

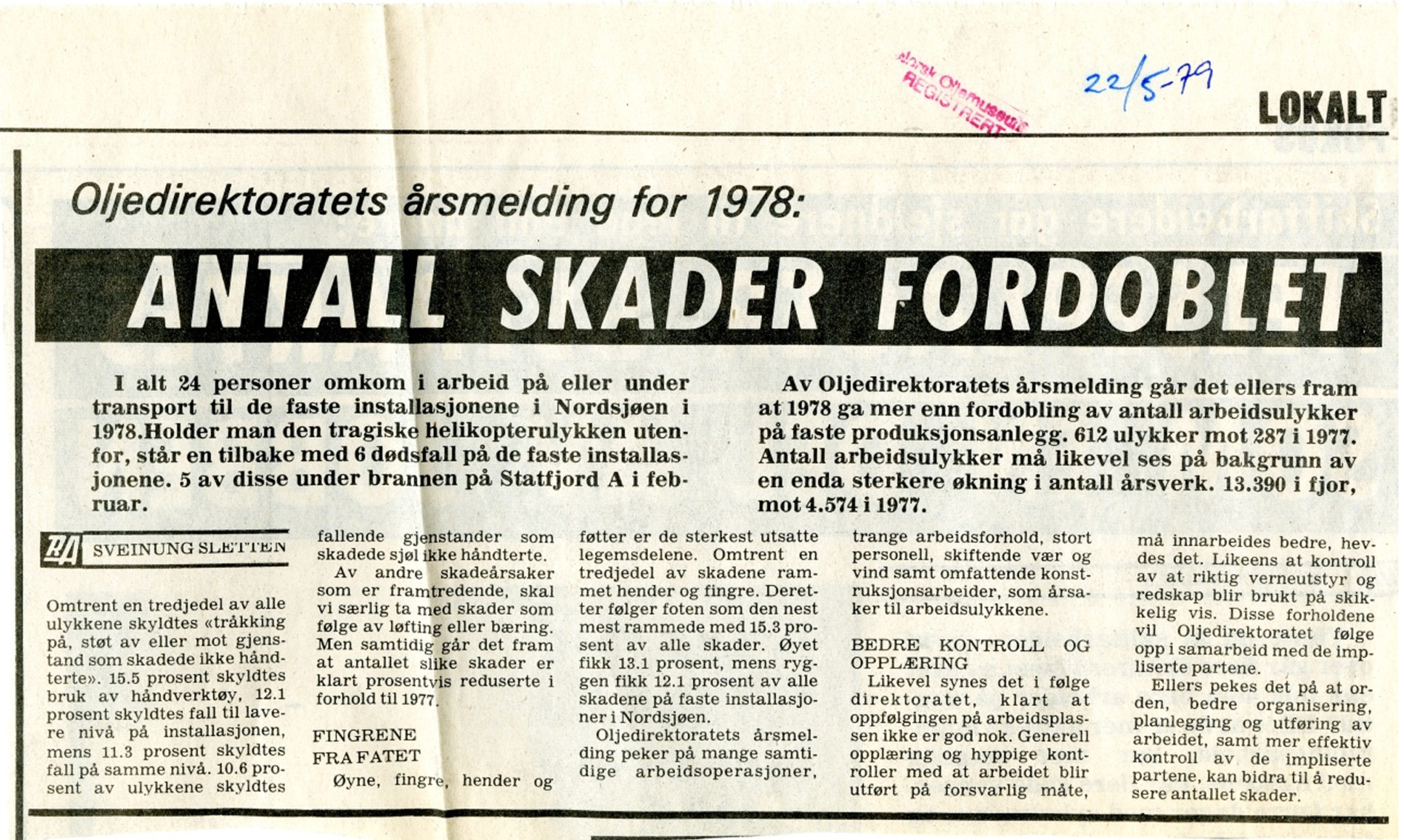

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,The work was labour intensive, with an average of 70-100 consultations per day. No less than 17 401 took place on Statfjord A in 1978.

Eye injuries were by far the most frequent complaint, either welder’s flash or foreign bodies. No less than 432 of 847 injuries related to the eyes – grit from sandblasting, or metal grains from welding or grinding.

Although that was a low figure compared with a large shipyard on land at that time, the foreign bodies were often hot and burnt into the eyeball. Twenty-four people were sent ashore with eye injuries in 1978. As a result of these high figures, the nurses were soon sent on courses to learn specifically about treating such damage.

A project was also launched to develop protective goggles which people could bear to wear. The available products were optically distorted, did not sit well and failed to provide proper protection. The outcome was the development of the “Statfjord goggles”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Wearing protective goggles was mandatory in certain areas of the Statfjord platforms. But it was difficult to motivate the workforce. Use of goggles was an important part of Mobil’s loss control programme, which aimed to prevent eye injuries. The company’s safety department developed a prototype for new protective goggles in close collaboration with the OHS and the safety delegate system offshore. These were “light, elegant and modern safety glasses”. Two opticians and a psychologist from the Work Research Institute with experience of vision physiology were involved in the project. The goggles had to be light but strong, heat- and rust-resistant, withstand burning from red-hot particles, have good brightness, withstand scratching of the glass, minimise optical distortion, have a modern design, and pinch neither nose nor ears when using heat protection. The Statfjord goggles were available from the autumn of 1983. Source: Mobil Explorer, April 1983.

A number of injuries were otherwise caused by blows or crushing, broken bones and amputation of fingers. People who failed to take off their rings were caught up in rotating machinery. Many falls also occurred in the early years. The decks were often slippery, and it was easy to trip over cables, tools and piping.

Where illness was concerned, the nurses were primarily presented with throat infections, headaches and musculo-skeletal disorders. A number undoubtedly visited the nurses – or medics, as they were known – in search of somebody to talk to about their family, boss or colleagues.

A total of 523 patients were sent ashore in 1978, half because of illness and the rest as a result of injuries. The decision on whether to send somebody back to land was taken by the nurse in consultation with the duty doctor.

Since up to eight helicopters were shuttling back and forth every day, getting patients ashore presented no problems. Keeping sick or injured workers on the platform was not appropriate. There was no hospital ward on board and lack of space was a constant issue. Patients seldom waited more than a day before being flown to Bergen, where they were attended by the duty doctor.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Knut Jørgen Jørgensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 29 April 2011.

Epidemics

Responsibility for preventing the spread of infection on the platforms rests with the operator’s medical officer. Although few in number, some epidemic infectious diseases have occurred on Statfjord.

Two cases of tuberculosis were recorded on the A platform in 1979 and 1983 respectively. In the first incident, the National Institute of Public Health X-rayed the lungs of 1 238 employees. At the same time, the medical office administered a tuberculin test for the whole workforce.

The discovery of TB on Statfjord was never a dramatic incident, but demanded a good deal of work. In the second case, X-rays were taken at the Flesland heliport while personnel were on their way offshore. Tuberculin testing was also carried out again. Many Americans worked on the field, and a number of them came from states where TB was widespread and vaccination not usual.

Fears of a large-scale offshore epidemic related primarily to food and drink. Minor outbreaks did occur, but were never threatening. The offshore nurses gave great emphasis to preventive work through food hygiene and drinking water checks. They made regular tours with the steward to check sanitary and hygienic conditions, and drinking water samples were taken on a daily basis and sent to the laboratory.

An outbreak of hepatitis A occurred on Statfjord C in 2000. Nine cases were recorded, all probably infected by the same source. All possibilities were investigated, and drinking water was eliminated. Nor could semi-processed food from land be implicated, because cases would then have been found on other platforms.

The most likely theory was food pollution, caused by poor hand hygiene on the part of somebody who had prepared it. Hygienic measures were tightened up on the platform, including a requirement for handwashing after each visit to the toilet and before serving food.[REMOVE]Fotnote: National Institute of Public Health, MSIS reports 25/2000 and 27/2000.

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) were also among the conditions often encountered by the Statfjord nurses during the early years. Scabies, pubic lice (crabs) and gonorrhoea were treated offshore.

Crabs were dealt with using an ointment which was smeared on the affected area. It had a strong odour and had to be left for a while before being washed off. Having to go to the canteen or explain to the other occupants of a cabin where the smell was coming from was unlikely to have been much fun.

To eliminate the risk of transmitting crabs, cabins had to be thoroughly washed and the nurses had to talk with the steward to get the catering staff to do this. The process was a burden both for the nurses and for the catering personnel, if not quite as burdensome as it was for the patient. But the period when that type of infection occurred has passed.

Some cases of delirium also had to be treated during the early years on Statfjord. People came offshore with withdrawal symptoms, but drug and alcohol misuse was not a big problem. The police carried out a couple of raids without finding anything.

These raids were not without their problems for the OHS personnel. The police used their facilities for taking samples and holding suspects, which gave the impression that the OHS was directly involved. It was important for the medical staff to be perceived as neutral, with a duty of confidentiality.

Jørgensen was concerned that drug users suffering from withdrawal would not dare to visit the nurses, and would fear that their medical details might be passed to the police.

The primary job of the OHS was to help the individual worker, regardless of their place in the system. That called for a trusting relationship which could not be reconciled with playing at being police.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Jørgensen’s archive. Letter of 4 June 1982. Police raids also got in the way of the normal daily activities in the OHS.

Health certificates in the early years

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,

Bedriftshelsetjenesten i et historisk perspektiv,Issuing health certificates was the largest part of the job for the medical officers on land. A certificate was required to work for Mobil offshore, regardless of the employer, but was not a formal legal requirement at the time. That was first introduced in regulations issued by the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs on 1 August 1980.

Jørgensen joined forces with Nome in Phillips to establish a standard for health certificates. This was later transferred to the Norwegian Board of Health and formed the basis for the regulations eventually adopted.

With up to 1 400 people working offshore at any given time, the tour rotas involved more than 3 000 personnel in total. Turnover was also high in the early years, so issuing health certificates for everyone was a big job.

Brown & Root supplied many of the construction workers on Statfjord A, and recruited a number of them from Europe and Latin America. A lot of these people were not in regular contact with a physician, and a number of those arriving from abroad failed to secure the necessary certificate owing to such conditions as epilepsy, problems with heart or vision, or poor hearing. People working on Mobil’s facilities had to be in a good state of health.

A number of the foreign workers had very poor dental health, and many had to be sent ashore with bad teeth, abscesses and gum disease. This prompted Mobil’s OHS to recruit a dentist. These problems diminished during the 1980s, and loss of fillings became the primary dental complaints.

To avoid having to send people ashore because of their teeth, the offshore nurses received training in simple techniques such as the use of dental cement and other temporary solutions which would hold until the patient’s tour was over.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Jørgensens arkiv. Inter office memo. 15. juli 1982.

Prevention

Statfjord A had been designed to use water-based drilling fluid or mud. But this had to be replaced with an oil-based variety, which posed a bigger health risk for those working in the mud room or on the drill floor.

Workers became covered in mud, and many suffered problems with eczema.[REMOVE]Fotnote: See the article on strikes. The mud was hot and lay in open containers (pits), which meant a good deal of oil vapour was given off. The OHS worked hard to prevent ill-health and to get people to wear protective gear.

But the preferable solution was to eliminate the source, and cover the mud pit. Jørgensen went to the drilling manager, an American, and asked why this could not be done. The manager probably thought this was the stupidest question he had ever been asked. The doctor must surely understand that they had to be able to see the mud.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Knut Jørgen Jørgensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 29 April 2011. Mud pits are enclosed today.

But it is not always possible to eliminate a source, and the correct use of protective gear then becomes a key requirement. The nurses spent a lot of time out in the process area to ensure that ear protection was being used and that everyone was wearing protective boots, gloves and goggles.

It took a lot of work to get people to adopt the correct gloves and the right type of breathing mask with the proper filter for the specific working conditions.

This is governed today by official regulations, and most people take wearing standard protective gear for granted. But a number of people still refuse the respect the ban on rings or piercings. Cases still occur of people who lose a finger because their wedding ring gets caught in moving equipment.

The OHS today faces other challenges. An aging workforce calls for new approaches to general health, acute response and overall OHS activity on Statfjord. (Note! The article is several years old. The average age may not be as high anymore.)