The Statfjord B letter

At that time, contract negotiations had been pursued with Norwegian Contractors on building a four-shaft Condeep gravity base structure (GBS). They were at the point where a letter of intent was ready.

The recently established Norwegian Petroleum Consultants (NPC) joint venture had also signed a contract on project management and engineering design for Statfjord B. Read more about NPC in the section on Statfjord B – the first plan.

While the contract for building the platform topside and mechanical outfitting of the GBS shafts had yet to be awarded, an option agreement had been secured with the Aker group.

So all the main contracts for the project appeared to have been put in place. The Storting (parliament) had also approved phase II of the development plan in June 1976, and most people assumed that it was simply a case of starting to build.

Until the NPD letter arrived

The Vogt commission

brevet,

brevet,New safety regulations for the Norwegian offshore industry had been adopted on 9 July that year. A key issue for Statfjord B and the field licensees was the introduction of a more restrictive attitude towards simultaneous drilling and production combined with living quarters on a single integrated platform.

The new rules had been developed by a commission of inquiry appointed by the government as early as 22 May 1970 with a mandate to propose regulations for the safety of production and storage facilities on the seabed and of exploiting petroleum deposits.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1976). no 2. Kontroll med sikkerheten fordelt på ni instanser.

Work in the commission progressed slowly and its chair, Jens Evensen, asked to be relieved. He was replaced in November 1972 by director general Lars Oftedal Broch, who was replaced in his turn during May 1974 by Nils Vogt from the NPD.

The latter gave his name to the commission’s report, which was submitted to the Ministry of Industry on 12 July 1975. It was then circulated for consultation to affected companies and institutions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Hanisch, T., Nerheim, G., & Norsk petroleumsforening. (1992). Fra vantro til overmot? (Vol. 1). Oslo: Leseselskapet: 324.

Adopted by royal decree of 9 July 1976, the new safety regulations were based on the recommendations of the Vogt commission and on comments received in the consultation process. One provision of the decree was that the NPD would bear primary responsibility for supervising fixed offshore installations.

Safety issues on Statfjord were viewed by the directorate through the prism of the new regulations. It kept the industry ministry informed about its work, and wrote the following in a letter dated 7 July 1976:

“Given the work being done on safety conditions, it has been found necessary to adopt a more restrictive attitude to those concepts which are based on combined drilling and production, where the living quarters are also placed on the same platform. The main intentions of the Vogt commission’s recommendations run counter to both combined activity and the above-mentioned placement of living quarters … The NPD would emphasise that combined drilling and production will only be accepted following individual analyses and assessments. The same applies to living quarters which it is proposed to place on a drilling/production platform. No final choice of concept has been made for Statfjord B, so no specific safety analysis has been submitted. Comments from the NPD will accordingly have to wait until it the actual conditions have been presented.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy.

In other words, the ministry had been informed of the NPD’s work and of its scepticism about the plans for Statfjord B. As the letter indicated, the regulator could not adopt a final position until the Statfjord Unit Operating Committee (SUOC) had approved the concept chosen for the B platform in late August 1976. Only then could the NPD conduct its own safety analysis.

Brevet,

Brevet,The results of the latter were presented to the Statfjord licensees in the above-mentioned letter of 11 November 1976, where the NPD questioned the safety of an integrated platform and ordered the construction of a separate quarters platform:

“The NPD is currently assessing the concept for Statfjord B on the basis of a general evaluation of the safety rules on the field in the light of the new regulations (royal decree of 9.7.76)

“Statfjord B is expected to involve:

- particularly complex and extensive production facilities concentrated on a single platform

- a large number of producing wells with high capacity, along with water and gas injection

- permanent living quarters for 200 occupants, which will be used by 400 people during the construction phase and possibly the drilling phase

- possible simultaneous drilling and production.

“The total risk is characterised by the contributions from each of the activities and processes which include the examples given above. The NPD’s assessment is that the total risk associated with these conditions lies at too high a level.

“In the NPD’s view, the best way to reduce the total risk would be to reduce the number of people who are present on the platform at any given time. The NPD has accordingly concluded that a separate quarters platform connected to Statfjord B should be built.”

This safety assessment was not confined to Statfjord B. Questions were also posed about the A platform, construction of which was far advanced at the time. It was due to be towed out to the field in six months.

“The considerations mentioned above also apply to Statfjord A, if to a somewhat lesser degree. The NPD would accordingly, on the basis of the provisions in the royal decree of 9.7.76, request that the company undertakes a new overall assessment of safety conditions [on this installation] in relation to the planned drilling and production programme, with particular attention paid to the accommodation issue.”

This letter was signed by Gunnar Hellesen, chair of the NPD board, and director general Fredrik Hagemann.

New concepts proposed

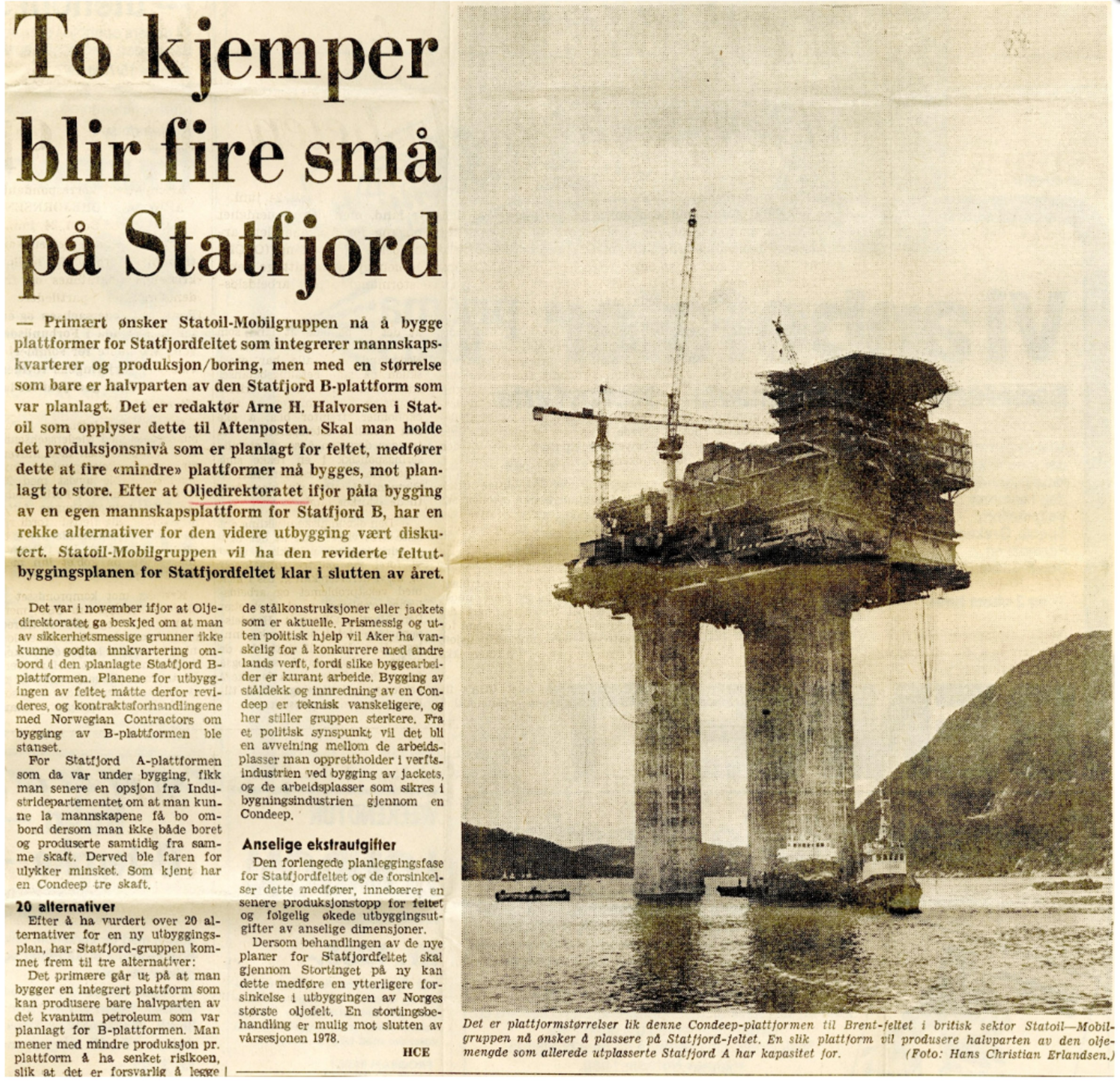

Statfjord B was intended to be a virtual copy of the A platform, but with four support shafts instead of three. The process facilities would be equally large and complex, with a production capacity of 300 000 barrels per day, and the 200-berth quarters module was to be installed on the platform.

It was the last feature in particular that the NPD wished to prevent. The regulator took the view that cutting the number of people on the platform at any given time would reduce the overall risk.

As the letter indicates, the desirable solution was seen to be the construction of two platforms – one for production and drilling, and the other for accommodation. The NPD also emphasised the need for overall safety thinking, and wanted a separate safety study carried out before detailed planning began.

Statoil and Mobil expressed surprise at the letter, and claimed they had not heard that such assessments were being made. Arve Johnsen, then Statoil’s chief executive, described his reaction to the letter in his book Utfordringen (The Challenge): “As chief executive of Statoil, I received many kinds of letters … I have forgotten most of them, but I will remember one to my dying day … It sent a shock wave through the licensees in the Statfjord group.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Johnsen, A. (1988). Utfordringen : Statoil-år. Oslo: Gyldendal: 202.

It might seem incomprehensible that the partners had failed to see this coming. They had long been aware that the NPD was looking at problems associated with simultaneous drilling and production, and the Vogt commission’s report had been through a consultation process. Comments in the latter as well as the report itself formed the basis for the new safety regulations.

Adopted in June, four months before the letter was despatched, the regulations specified that simultaneous drilling and production was prohibited without special permission. This should have sent certain signals that the plans for Statfjord B might be more difficult to implement than Mobil and Statoil thought.

As late as 12 October, section head Harald Ynnesdal had explained the NPD’s view on the issue in a speech he gave in Kristiansand:

“The new platform types are particularly complex and difficult to assess from a safety perspective with regard to these combined activities. As far as possible, fields should be planned with separate quarters platforms. The production platforms could then, with their combined activities, be assessed purely as industrial plants.

“In an assessment of simultaneous drilling and production in the Statfjord project, for example, the problem would have been much simpler if separate quarters platforms had been adopted. The cost of such platforms would have had little effect on profitability for this project, but would have meant a great deal for overall safety and the desire for an early start to production.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1976). no 9. Statfjord – planer og virkelighet. On the basis of this letter, an extraordinary meeting of the SUOC was called on 26 November. It decided that all activities related to Statfjord B would be halted. The project would have to be re-evaluated, and extensive conceptual studies were to be carried out for every option from one to three platforms.

brevet,

brevet,A meeting of the Statfjord field engineering committee (SFEC) – the technical project team – took place in January 1977. A 35-strong sub-committee was appointed to study and assess various conceptual solutions for Statfjord B, and came up with 39 variants for consideration.

When the SUOC met again on 18 March, Statoil expressed concern at the progress made. The project had a tight timetable, and order books at the Norwegian shipyards were empty. To speed up the process, the company proposed a separate drilling platform linked by a bridge to a combined production and quarters unit.

A drilling platform supported on a steel jacket, for instance, would be relatively cheap to build and could be ready for tow-out as early as 1979. Drilling of production wells could start as soon as the platform was in place, and continue while the associated production and quarters facility was under construction.

As soon as the latter had been installed, oil and gas could thereby begin.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1977). no 5. Industrien må fortsatt vente på Statfjord B. This meant in turn that the original schedule set in the field development plan could be met.

Mobil and Saga were strongly opposed to this plan, but did not have enough votes to block it. Their interests added up to only 25 per cent, while resolutions in the SUOC needed 70 per cent support. The Statoil proposal was thereby adopted – against the operator’s vote.

Esso also proposed its own solution at the meeting, comprising an integrated production, drilling and quarters (PDQ) platform but with processing capacity halved to 150 000 barrels per day. This facility would be simpler, since only one process train was required rather than the original two, and overall safety would be improved.

Mobil supported the Esso proposal. The two companies were uncompromising in their opposition to two platforms, and maintained that this would provide no safety benefit. A factor in their assessment was the poor seabed soil conditions on Statfjord, which meant that installing two platforms so close to each other and linked by a bridge carrying high-pressure pipelines would pose a safety risk.

The thought of the substantial capital investment required for two platforms also worried the operator. On the other hand, experience from other North Sea projects suggested that a capacity of 150 000 barrels per day would be sufficient. Such a solution would reduce construction costs by simplifying the platform, and production could also start earlier.

Threats

A further meeting of the SUOC was held on 28 April, when Mobil proposed an integrated platform with a single process train and an average capacity of 180 000 barrels per producing day. This size had been chosen in the hope of avoiding a separate quarters platform.

The change to the original concept was so large that a completely new field development plan might have to be produced. According to the proposals approved the Storting in the summer of 1976, three platforms with a combined capacity of 900 000 barrels per day were to be installed.

Reducing the size of the process facilities on each platform would either require more structures to maintain the planned output, or a slower pace of production.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1977). no 5. Industrien må fortsatt vente på Statfjord B. Fresh consideration by the Storting could delay the project further.

At the same time, Mobil vetoed a separate quarters platform.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Moe, J. (1980). Kostnadsanalysen norsk kontinentalsokkel : Rapport fra styringsgruppen oppnevnt ved kongelig resolusjon av 16. mars 1979 : Rapporten avgitt til Olje- og energidepartementet 29. april 1980 : 2 : Utbyggingsprosjektene på norsk sokkel (Vol. 2). Oslo: [Olje- og energidepartementet]. With strong support from Esso, the operator noted that it could not accept a solution which complied with the NPD’s principle that drilling and production should not take place simultaneously on the same installation.

Brevet,

Brevet,Clear instructions had been sent from Mobil’s head office in New York that a compromise solution which would involve an acceptance of the NPD principle was out of the question. It feared that conceding this demand from the Norwegian regulator could lead to similar requirements on other continental shelves, which would have major consequences for both Mobil and its fellow oil companies.

A telex from New York emphasised that, the way things looked, concrete platforms on the scale of Statfjord A had outplayed their role on this field. Mobil was willing to renounce the operatorship for Statfjord B if a two-platform solution was adopted. This attitude took Statoil and the Norwegian government by surprise.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norsk Oljerevy. (1977). no 5. Industrien må fortsatt vente på Statfjord B.

Statoil explored the possibility of another operator, but none of the other partners was willing to take on the role without a reallocation of licence interests. Mobil and Esso had staked their prestige on the issue, and they finally managed to convince Statoil of the technical problems posed by a two-platform solution. The argument that this could affect later developments in deeper water was central to the Norwegian company’s change of mind.

The discussion on one or more platforms and the studies of various concepts were paralleled with the presentation of new seismic data for the field. These cut its estimated oil reserves from 3.9 billion barrels – equivalent to 527 million tonnes – to 3.2 billion or 432 million tonnes. That reduced the need for two process trains on Statfjord B.

Clarification

On 5 August, the SUOC approved plans for a platform with the capacity to process 180 000 barrels per day. It was resolved on 29 November to apply to the NPD for permission to build such a structure. The application, accompanied by a separate safety study, was submitted on 1 December.

Plans now called for Statfjord B to be installed in 149 metres of water at the southern end of the field. Seabed conditions were poorer there than over the rest of Statfjord, and the base area of the GBS accordingly had to be increased.

While Statfjord A had 19 cells, the B version would have 24. Planned topside space would expand correspondingly, from 5 200 square metres to 7 800. The platform would still have four shafts even though only one process train was to be installed. With the fourth shaft reserved for risers, space was freed up in the others.

Additional safety barriers were introduced by the decision to make the decks and modules open, reducing the danger of an explosion and possible damage from such an incident. The various functions would also be positioned in such a way that no hazardous operations were close to or beneath the living quarters. And the quarters modules would be protected by an additional fire wall. These plans were approved by the NPD on 19 December.

The project had been delayed by a year and incurred substantial costs through a number of conceptual studies and reports. According to Henrik Ager-Hanssen, deputy chief executive of Statoil, the letter from the NPD was the most expensive in Norwegian history and cost the project NOK 25 million per word.

Viewed from a different perspective, former Statoil staffer Bjørn Vidar Lerøen has noted that oil prices reached record levels over the next few years. That meant the letter became one of Norway’s most profitable.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lerøen, B., Gooderham, R., & Statoil. (2002). Drops of black gold : Statoil 1972-2002. Stavanger: Statoil: 149.