Building the topside

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketMRV had specialised in recent years in building gas carriers, but was now going to outfit a module support frame (MSF) covering no less than 7 800 square metres. Its Rosenberg Verft yard in Stavanger had to be further developed before work could begin.

The latticework MSF was to be established on four concrete pillars which corresponded exactly with the tops of the GBS shafts. Installation work started in November 1978. Space also had to be made available for storing materials, building modules and – since the labour force would necessarily expand considerably – places to eat, sleep and work. Rosenberg Verft had 1 700 permanent employees. In addition, blue-collar and white-collar workers from a number of sub-contractors, service companies and Mobil had to be found space at the yard’s Buøy site. Some 3-4 000 people were due to be working there during the Statfjord B project.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Roalkvam, G., & Stavanger jern- og metall. (2002). Fra ambolt til plattform : Jern- og metallarbeiderne i Stavanger. Stavanger: Wigestrand: 149

Four hectares were added to the site, in part by filling in the bay off the yard and burying the Kattaskjæret rocks – where the topside was to stand – under spoil. The seabed was blasted and dredged to install a deepwater outfitting quay suitable for both offshore facilities and big ships.

Utslepet av Statfjord B understell til Gandsfjorden, bygging av b-dekket,

Utslepet av Statfjord B understell til Gandsfjorden, bygging av b-dekket,The former mould loft was converted into a drawing office for 60-70 people. Temporary buildings were established in the quay area to provide accommodation for 300 people and canteens for 500. Rosenberg Verft also had five accommodation blocks with beds for 25-30 people in each.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 372.Blasting work was completed on schedule in mid-February. The four concrete pillars to support the MSF were ready to be towed out of the dock in late April and in position during May.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 372-375.

The MRV board also resolved in February to invest another NOK 140 million in upgrading the facilities. Just over 1.4 hectares of land was acquired to accommodate new warehousing, changing rooms and a canteen. Two warehouses were built for intermediate storage of shaft equipment, along with a temporary pipe welding shop. In addition came a new sandblasting and painting shop, further production and transport equipment, and a new office and administration building.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 373.

Work advances in Fredrikstad and Egersund

The latticework MSF was to be built in two identical halves at Fredrikstad Mekaniske Verksted (FMV) south-east of Oslo and Kværner Brug Egersund (KBE) south of Stavanger respectively.

Eighty people worked at the latter on a structure measuring 114 by 55 metres, with a height of 14 metres to the main deck. The total weight of this colossal frame was no less than 2 400 tonnes. Its steel plates were up to 50 millimetres thick.

The timetable was tight, and delays could have serious consequences for the rest of the project. Whether the Egersund and Fredrikstad yards would succeed in meeting their delivery deadlines was the first major source of uncertainty in the construction of the Statfjord B topside.

Both fabricators fell a little behind schedule initially because of problems with approval of welding procedures. Welders had to be certified to the American ASME standard, and needed a special course to achieve the required G-6 grade. The weld quality demanded was very high, and it took longer than expected to get the necessary procedural tests approved.

The problem was overcome, partly because in-house welders acquired the necessary certification and partly by hiring in specialists from Sweden and Finland. In addition, the yards succeeded in getting the delivery date extended by two weeks because a good deal of extra work was added for the MSF sections.

KBE operated at full throttle, even during the Easter holiday. The Directorate of Labour allowed it to work throughout the public holiday except for Easter Sunday, when the yard itself wanted a well-earned break.

It was not difficult to get people to work at Easter. Many of the personnel at the yard came from other parts of Norway or the Nordic region, with a long journey home for just a few days off. The financial advantages of working on public holidays were another motivating factor.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1979, 17.april . Travel påske ved Kværner.

FMV built the other section in parallel. The work progressed, but the yard had problems recruiting qualified welders. Other Norwegian yards had promised to help with skilled personnel, but few actually turned up. FMV accordingly had to hire 150 specialist welders from Sweden, and eventually eliminated the delays.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 376.

When the FMV union downed tools in May for a one-hour “political” strike, along with 250 white-collar staff, a number of people expressed concern about progress with the Statfjord B project. The stoppage was implemented to persuade the government to secure new work for the yard. Like the rest of Norway’s shipbuilding industry, FMV was hard-hit by the international crisis in the shipping industry.

The union branch decided at the same time that all overtime working would halt immediately and demanded that further recruitment of contract labour should cease. The Swedes and Finns already at the yard were allowed to remain.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Demokraten. (1979, 9. mai). Vil forsinke utbyggingen på Statfjord B.

Til tross for uroen blant verkstedarbeiderne ble den justerte fristen 14. juli 1979 overholdt. 15. august var dekksrammen i Egersund ferdig, også det innen fristen.

Despite the unrest among the yard workers, the adjusted deadline of 14 July was met. KBE also completed its section of the MSF by the set date of 15 August.

Shaft outfitting

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketOnce the expansion and upgrading of Rosenberg Verft’s Buøy site had been completed, work began on prefabricating equipment for mechanical outfitting of the GBS shafts. This included decks, stairs, ladders, platforms, foundations and ventilation channels, which could then be lifted into the shafts as the latter were slipformed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Roalkvam, G., & Stavanger jern- og metall. (2002). Fra ambolt til plattform : Jern- og metallarbeiderne i Stavanger. Stavanger: Wigestrand: 149.

The equipment was commissioned at the yard by MRV’s own personnel, while installation in the nearby Gands Fjord was carried out by sub-contractors.

Things went a little slowly to start with. Rosenberg Verft failed to increase its prefabrication workforce to the planned level. The work fell steadily behind schedule, and the management sent a request to Mobil for an extension of the deadline. This was refused point blank. To boost progress, new steps were taken in May to recover the time lost.

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketAs early as 1978, the local union branch and the management had entered into an agreement on the use of contract labour. Nobody wanted the number of permanent employees to exceed a natural workload.[8] In order to execute the project within the tight deadline, it proved necessary to hire in people and allocate part of the work to sub-contractors.

The union and the management agreed to give priority to reputable Norwegian companies who were able and willing to accept full employer responsibility for their own personnel while they were engaged on Rosenberg Verft’s premises.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Roalkvam, G., & Stavanger jern- og metall. (2002). Fra ambolt til plattform : Jern- og metallarbeiderne i Stavanger. Stavanger: Wigestrand: 375.

Workers were hired as far as possible from Norwegian industry, but MRV also had to take people from the rest of the Nordic region. Domestic personnel were in particularly short supply in such skilled trades as specialist welding and sheet metal work, so Swedes and Finns had to be recruited.

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketUnder the deal with management, the local union had the right to express its views on which companies should be asked to tender for various jobs. It received help from the Norwegian Union of Iron and Metal Workers (NJMF) centrally to identify which companies were responsible and which could not be recommende.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1979, 21. november). Leigefirmaene skor seg.

Ali Installation A/S, for instance, was a subsidiary of Sweden’s Asken Industri AB. It had long experience of platform building in Stavanger, having leased substantial numbers of workers to Aker for outfitting the shafts of the Beryl A and Statfjord A GBSs a few years earlier. Some 70-100 specialist welders were recruited from this source.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 376-380.

Particularly stringent demands were set for welding pipe – and a lot of pipe was welded at Rosenberg Verft during this period. A welder had to demonstrate that they could weld in an arc or circle, and not just along a straight line.

When welding pipe, it was not always possible to get at the weld site from the inside. The seam between the pipe ends therefore had to be filled right through. And the filling had to display an exactly even pressure throughout its length, entirely free from pockets or irregularities.

Welds were carefully checked on a daily basis with such methods as X-rays and ultrasonics. No cavities were tolerated, and quality control was carried out by several bodies.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil magasinet. (1980). 1.

Work was to begin in May, but this proved impossible because materials had not been supplied by the engineering management contractor (EMC), a joint venture between Brown & Root and Norwegian Petroleum Consultants (NPC).

Rosenberg Verft received both ordinary and isometric[REMOVE]Fotnote: En isometrisk tegning viser to sider av et objekt, I tillegg til topp eller bunn. Alle vertikale linjer tegnes vertikalt. Alle horisontale linjer tegnes med 30º vinkel I forhold til horisonten.drawings from EMC, but the quality of these and of the specifications was poorer than the yard had expected and too many of them had to be revised.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Aftenposten. (1979, 15. mars). Statfjord B efter tidsskjema, men skal stå fullført i tide.

The cellar deck

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketDeliveries of drawings and materials had been late throughout the spring of 1979, and outfitting work for the topside was behind schedule. During the summer, however, drawings and materials for several months of work were delivered to Rosenberg Verft. With its contract personnel, the yard had secured a sufficient workforce to increase the tempo and recover some of the lost ground.

Both sections of the MSF were delivered in accordance with the revised schedule. The first structure from FMV was installed on the pillars at Kattaskjæret on 10 August, with the second from KBE following on 21 August.

These were large and heavy units which had to be positioned with a precision measured in millimetres. Local daily Stavanger Aftenblad had a reporter on the spot when the MSV section from KBE had to be moved 80 millimetres to provide the space to weld in the connection piece. He was clearly impressed by the precise character of the work.

Weighing 2 400 tonnes, the section was moved by emptying ballast tanks in the barge on which it lay so that only 55 tonnes continued to rest on the pillars. Project planner Per Gunnar Andersen at Rosenberg Verft explained how the operation was conducted: “We then jack it only 80 millimetres in, so that we have three millimetres of clearance between the girder and the connection piece.»[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1979, 4. september). Varmt som i badstu og tre millimeter klaring.

Three millimetres was not much on a structure which extended 20 metres above the sea surface, but was crucial for welding the two sections together with the six connection pieces.

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketThis was tough and hot work. Specialist welding was carried out inside the hollow steel girders which made up the MSF. Space was limited and ventilation minimal. The internal temperature was 70-80°C because the steel had to be heated to 125°C before welding could begin. Such preheating was necessary if the steel plates – up to two inches thick – were to harden properly. It was accomplished by placing heat mats on the weld area.

However, the heat propagated through the steel, and a welder could only remain inside a girder for 15 minutes at a time before they needed to breath fresh air and let somebody else take over. Each welding team comprised three people who constantly changed places.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1979, 4. september). Varmt som i badstu og tre millimeter klaring.

Once the two sections had been joined, they comprised that part of the topside structure known as the cellar deck. This was divided into a total of 15 areas with space for masses of equipment and structures. Fourteen of these areas were built and outfitted by Rosenberg Verft. Because they lacked walls and roofs, these were called “pancakes” – by contrast with the Lego-like modules to be placed on top of the MSF.

Lifting into cells and shafts

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketThe Uglen crane ship owned by the Grimstad-based Uglen group began lifting the first load of equipment into the GBS cells in mid-August 1979, only a week behind schedule. This vessel carried a crane 110 metres high with a lifting capacity of 450 tonnes.

Work went according to plan, and collaboration between GBS builder Norwegian Contractors (NC) and MRV functioned well. The high crane on Uglen was demounted in October for a break until the work of lifting decks and equipment into the shafts began.

The ship returned in March, when slipforming of the shafts had reached the full height of 171.3 metres – 58 of them beneath the surface of the sea. This work was completed one day ahead of schedule.

Rosenberg Verft had been given six weeks to lift in the equipment, which was all due to be installed by mid-October 1980. Prefabricated decks and other hardware were carried by the crane ship from the yard to the fjord where the GBS lay, and lifted directly into the shafts.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Nerheim, Jøssang, Utne, Dahlberg, Jøssang, Lars Gaute, Utne, Bjørn Saxe, . . . Kværner Rosenberg. (1995). I vekst og forandring : Rosenberg verft 100 år 1896-1996. Stavanger: Kværner Rosenberg: 378.

Each component was attached to the hooks on Uglen at the yard and hung from the crane throughout the five-kilometre trip to the mooring site of the concrete structure.

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketThis work began on 16 March 1980. The individual decks were first hoisted into the utility shaft before the work of connecting them to the concrete walls started. Great accuracy was required and depended on stable weather conditions. The crane driver had to manoeuvre very precisely, since a single deck could weigh up to 400 tonnes and its clearance from the concrete wall was no more than 40 millimetres.

A good deal of the equipment due to be installed was large and difficult to put in place. The tanks for ballast water, for instance, were 11.5 metres long and six metres in diameter. Once lifted 115 metres, they allowed little room for error when being lowered into the shaft.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status (1980). nr 5-6. Nytt fra Statfjord.

Lifting into the topside

Plans called for the MSF to be ready for module loading by 8 December 1979. In fact, the lifting operation began before that date, and a number of the prefabricated “pancakes” were put in place during December. Mobil was very pleased with the progress. A full storey of modules was installed on the MSF, and topped in its turn by a new set of 21 modules. Each of the three stories was 14 metres high.

The lifting operation was conducted over four periods. Installation in the actual MSF took place during December 1979. Seventeen modules, equipment packages and not least the quarters followed in May 1980. Dutch crane ship Balder lifted a total of 10 000 tonnes in this round, with the heaviest single lift – 1 200 tonnes – needing to be installed on the topside with 35 millimetres of clearance on each side.

Modules came from both Norwegian and foreign fabricators. These structures were packages of equipment as well as three complete quarters modules, each eight stories high.

Balder was positioned between Rosenberg Verft and the maritime college on the other side of the fjord, and moored with cables attached to six points on land at Karlhammeren, Ulsnes, Rosenberg and Tjuvholmen. The sound is 200 metres wide at this point, so there was not much room for other shipping.

Since it had a displacement of 20-25 metres and the water depth at Rosenberg Verft’s quay was only 12 metres, Balder lay in the middle of the sound and blocked the shipping channel into the port of Stavanger. Lifting operations had to be suspended for a few hours every day and the mooring lines slackened for ships to pass. Small craft could take a small diversion through the islands to reach harbour.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1980, 6. mai). Kjempeløft tross tåken.

Balder’s sister ship, Hermod, was ready on 23 June 1980 to perform the final topside lifts on the. Because of delays at the Franco-Norwegian joint venture UIE/Sterkoder in Kristiansund, Hermod was nevertheless forced to return in November to lift on the drilling modules. Everything was then in place except the 120-metre-long flare boom. This distinctive component was not installed until the topside had been mated with the GBS at Vats.

Modules from Stord

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketAfter losing the topside contract, Stord Verft had secured responsibility for nine prefabricated pancakes. But the biggest job at Stord went to Leirvik Sveis in the form of the quarters modules. This company was responsible for the whole project from design to procurement and fabrication.

Leirvik Sveis had also built the quarters module for Statfjord A, but then as a sub-contractor to Stord Verft. It now entered into a direct contract with Mobil after lengthy negotiations, as chief executive Harald Karlsson recalled:

“I think we actually negotiated with them for six-eight weeks. We were inexperienced in such talks. They were all conducted in English, which we weren’t used to. We hardly understood everything we negotiated on – and in any event not the insurance terms.»[REMOVE]Fotnote: Myklebust, A., & Leirvik sveis. (1996). Leirvik sveis 50 : Jubileumsbok for Leirvik sveis. Stord: [Leirvik sveis]: 116.

Leirvik Sveis – known colloquially as “Sveisen” (the Welding Shop) – had 50-70 employees. The company decided that it would stick with the job it was best qualified to do, namely the steel work, and use sub-contractors for everything else. It did not create its own organisation for the disciplines contracted out, but allowed the sub-contractors to establish their offices close to the fabrication site.

Engineering services were purchased from Norconsult in Oslo, where 30-35 people worked exclusively on Statfjord B. The quarters modules also included the helideck, which was fabricated at Stord Verft, and a helicopter hangar. The latter had not been part of the Statfjord A job.

The modules were constructed in the space of a year and employed 300 people at peak. With the aid of sub-contractors and about 50 contract administrators, the work was done on schedule.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1980, 19. april).

Exemptions from the Working Environment Act

Bygging av B-dekket

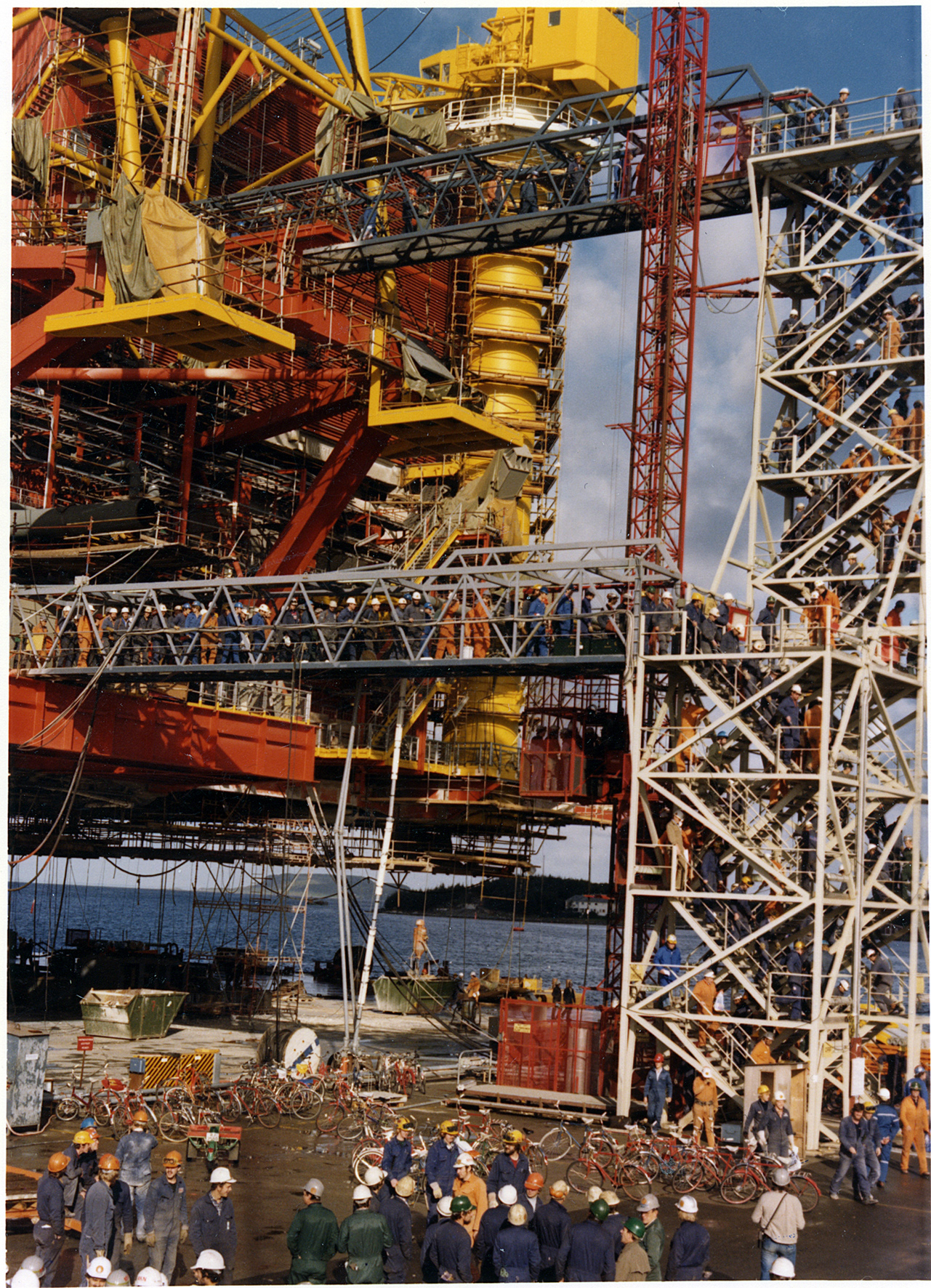

Bygging av B-dekketSeveral of the module-builders failed to complete their work on time. Rosenberg Verft accordingly had to take over part of the work so that the pancakes and modules could be installed on the topside. A total of 1 900 people were at work on the structure by 30 April 1980, including 800 personnel acquired via sub-contractors and temporary personnel agencies.

During the summer, the yard was still short of specialist pipe welders. But the lack of electricians and instrumentation installers was also beginning to be parlous. Neither EGA or Incom, responsible for electrical and instrumentation installations respectively, were able to secure enough skilled personnel in time. The Statfjord B topside began once again to slip behind schedule.

To secure the necessary workers, Rosenberg Verft launched a major advertising campaign and contacted labour exchanges directly throughout the country. It was looking for pipefitters, specialised welders, sheet metal workers, heat treatment operators, crane drivers, transport workers, electricians and cleaners. But the response was poor.

The yard was accordingly forced to turn to expensive agencies. While the topside contract had allowed for using external personnel, the need was greater than expected. Hiring in personnel was more expensive than recruiting employees. The yard had to make extra payments under collective wage agreements for living away from home, as well as meeting the cost of accommodation, food, travel home and agency management.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1980, 19. januar). Kostbare leiefolk.

To use contract personnel, Rosenberg Verft had to secure an exemption from Norway’s Working Environment Act. This was granted for the first three months by the County Employment Office without difficulties. Beyond that point, an application had to be made to the Directorate of Labour, which took a very serious view of a long-term arrangement.

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketThe Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) was also sceptical about temporary personnel agencies and extensive use of contract labour. Such workers wanted different working time arrangements than permanent employees, drove up wages and increased inflationary pressures.

According to the Working Environment Act, it was forbidden for employees in one company to do work for another firm which already had personnel able to do jobs of the same kind or who pursued a business where such work formed a natural part of the activity.

The LO could not accept breaches of Norwegian law in order to execute major development projects, and blamed the government and the developers for setting construction deadlines which were too short. According to the confederation, financial considerations were being prioritised ahead of socio-economic aspects and it would fight this.

Most of the contract personnel wanted to work three weeks in a row, including weekends, and have the following week off. The normal working time was four weeks work with Sundays off and the following week free. Working on Sundays contravened the Working Environment Act, but Rosenberg Verft nevertheless applied for an exemption.

Its calculations for the topside contract had included the opportunity to work on Sundays and to hire agencies workers as and when necessary.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1980, 10. mai). Gjestearbeidere – oljealderens rallar.

Both the union branch at the yard and the Federation of Norwegian Industries (MVL) recommended that the application should be granted. Changing to three weeks continuous work would benefit not only all long-distance commuters but also the progress of the project.

The yard had an exemption until May 1980. Contract personnel lived for three weeks in the work camp and then had nine days at home. This meant they could have as normal a family life as possible. But using contract workers and exemptions from legal working time were the subject of intense discussion in the media during the spring of 1980, and the personnel involve found themselves squeezed between the Norwegian Working Environment Act and a desire to live as normally as possible.

With only three weeks in the work camp, the need for consolation drinking and drunkenness in the quarters would be reduced. It was maintained that making camp residents work four weeks at a stretch with Sundays off would guarantee drunkenness and fighting on the third weekend.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1980, 10. mai). Gjestearbeidere – oljealderens rallar.

An important consideration for the LO was that such an arrangement would not only apply to the long-distance commuters but also involve a number of the permanent employees. Its national organisation demanded respect for the law, and the issue went all the way to the Ministry of Local Government and Labour. Both Mobil and particularly Statoil put heavy pressure on the government to secure exemptions.

In addition to the working time issue, MRV had to secure permission for further recruitment of contract workers. This issue rumbled on in the media for a long time. Finally, the company reached a compromise settlement with the ministry and the LO which exempted the yard from the provisions of the Working Environment Act from 1 July 1980 to 1 April 1981. While it was admittedly refused permission for Sunday working, Rosenberg Verft was allowed to operate a three-week tour where employees had to be back at work after just seven and a half hours instead of the legal minimum of 10 hours.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende. (1980, 2. juli). Statfjord B.

The contract workers earned a good reputation. They worked hard and were skilled at their job. While their hourly pay could be up to 20 per cent higher than for their Norwegian opposite numbers, they were heavily taxed – particularly on their living allowances – and faced a more uncertain future. They could risk being jobless at two week’s notice. But the alternatives were not bright, particularly for the Finns. Their options were either unemployment or substantially lower pay as a skilled worker at a Finnish shipyard.

Work and working time

Welders and sheet metal workers were not the only trades required to complete the topside for Statfjord B. Much of the work on the MSF required scaffolding, both fixed and suspended. Erecting this was a demanding job for specialists.

Much of the scaffolding was on the outside of the structures, and working on it could be both chilly and wet. Work had to be suspended if the wind and rain became too much. As soon as screens were in place, however, the weather was no handicap.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad. (1979, 4. september). Varmt som i badstu og tre millimeter klaring.

A difficult neighbour

Work on Statfjord B was claimed to have destroyed life for local residents around the yard. While most people in Stavanger celebrated the huge contract and the construction project at Rosenberg Verft, not everyone was equally happy.

Residents on Buøy (part of an island connected to the city centre by bridges) found themselves with a massive building site at the bottom of their gardens. Large lorries thundering past, racket from the yard, the noise of hammers beating on steel and ever expanding work camps with everything these entailed set their stamp on the Bangarvågen area where Rosenberg Verft was located.

“A whole city district raped on Buøy” read one headline in local daily Rogalands Avis during June 1979. The residents felt powerless, and that nobody cared about them. Parents of small children were abused when they tried to curb the traffic. “Look after your kids, keep them in the garden,” was the response from the lorry drivers. “We’re driving on piece rates and short of time”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1979, 13. juni). Bydelen som ble voldtatt.

The issue flared up again in September 1980. Under the headline “Come and live with us, Rettedal” – an invitation to the mayor of Stavanger ¬– Rogalands Avis again wrote about the degradation of the residential environment in Bangarvågen

According to residents, the area stank of sewage, it was noisy around the clock and traffic in residential streets was at motorway level. Nobody respected the 30 kilometre-per-hour speed limit. Traffic flowed from 06.00 in the morning to 01.00 the following night. When the shifts changed at 23.30, four buses drove in and out of the residential area.

Noises from the yard never ceased, with banging and crashing around the clock. The worst offender was perhaps the sandblasting shop, which was close to the houses.

In addition came the sewage stench, which derived from a pumping plant in the work camp. Large volumes of sewage from the yard were pumped into the existing drains, and the pressure created a dreadful stink. Residents felt deceived by the city council, which had promised to deal with the problem.

They complained that nobody had initially mentioned any private motoring in and out of the yard, only necessary goods and service traffic. In addition, a new flotel arrived without warning at Bangarvågen in September 1980. Safe Bristolia was a barge outfitted with quarters modules which could accommodate 500 people. When it moored, the residential area was completely surrounded by the Statfjord B facilities.

Residents were at their wit’s end, and invited mayor Arne Rettedal to come and live with them for a week to see for himself how the neighbourhood was being destroyed.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1980, 23. september).

On the same day this the article appeared in Rogalands Avis, Rosenberg Verft itself asked the city council to look at the issue.

The yard wanted the politicians to decide on speed limits in the surrounding streets, define traffic routes to reduce the constant minor accidents and collisions, and install pavements. In response, the council promised that its executive committee would consider this request at its very next meeting. It also wanted to study plans for MRV and the council to buy out the local residents and convert the whole area into an industrial zone.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis.. (1980, 9. oktober).

The eventual solution was that Rosenberg Verft should buy up the properties in the Bangarvågen and Tømmerodden housing estates, which bordered the yard. Stavanger council would provide replacement housing sites. Although this was not finally decided at the time, it looked likely that MRV would also build the Statfjord C topside.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rogalands Avis. (1980, 22. november).

Bomb threat

Few accidents occurred while constructing the Statfjord B topside, but a bomb threat was received in April 1980. “I have a message,” an anonymous caller told the switchboard at Rosenberg Verft. “Things will happen on Statfjord B tonight. I hope there won’t be many people on the platform.”

The police fine-combed the whole topside without finding either bombs or anything else which might be related to the threat. Work was not interrupted, but the meal break for the evening shift was extended by an hour while the police searched the yard. Nobody was evacuated.

It proved impossible to establish who was responsible for the threat, and no more were received. The case was shelved.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Politikammers arkiv. Justissaker. Sak 2373/80.

The final lap

Bygging av B-dekket

Bygging av B-dekketDutch crane ship Balder returned to Stavanger in November in order to lift the last modules from their transport barges and onto the topside. The sailing channel into Stavanger was again closed, as with the two previous lifting operations. This job was pursued without incident, and the channel could be reopened just two days later.

Progress with the project was good towards the end of 1980, although parts of the installation work lagged a little behind. More personnel were brought in, with 2 555 people employed on the topside in January 1981 – 800 more than planned.

But the Christmas holidays disrupted efforts to speed up the job. Part of the instrumentation, electrical, insulation, painting and equipment testing work was not completed in time, and had to continue at Vats and out on the field.

In mid-March 1981, the barges which were to carry the topside to Vats for mating with the GBS were in place. The structure was lifted off the pillars on 20 March.

Time for celebration

Rosenberg Verft held open house on 1 March 1981. Special invitations were extended to the families of employees to visit the site and get to know the workplace. Most of them were inside the yard gates for the first time.

They were given a guided tour of the topside and allowed to eat as many buns and Danish pastries as they could manage. Lemonade, ice cream and coffee could be consumed while Buøy School‘s marching band paraded around and played.

Once the construction of the Statfjord B topside had been completed, MRV also invited its employees and a number of other guests to a big party in Stavanger’s Siddishallen ice rink. Three thousand people assembled for entertainment, food and drink. Praise and flowers were shared out, along with NOK 300 000 to Stavanger’s Central Hospital.

The mood was further enhanced when MRV announced that it had resolved to construct a new welfare building for its Stavanger workforce at a cost of NOK 5 million. This would stand outside the actual fabrication yard, and provide facilities for physical training and meetings. It was completed in 1983.