Statfjord’s significance for Statoil

It all began when Esso and Shell discovered the major Brent field in the UK sector of the North Sea due west of the Sognefjord. These two international companies then approached the Norwegian government in February 1972 to secure a set of blocks adjacent to this discovery on Norway’s side of the boundary. The question was whether Brent extended into the Norwegian sector.

Licence award

The Ministry of Industry was concerned that the British might drain a possible Norwegian share of Brent before Norway succeeded in mapping its side of the area. So it was a matter of urgency to explore the blocks in question, and extremely important to protect Norwegian interests in possible new oil deposits.

America’s Phillips Petroleum Company Norway had discovered Ekofisk in 1969 and begun test production in June 1971. French Elf found Frigg in the spring of the same year, and was planning the development and operation of this gas field.

But it was by no means given that Shell and Esso should get the next big chance. Through their “10 oil commandments”, Norwegian politicians had signalled that they wanted stronger national participation in the oil industry. But Statoil, which was created by the Storting (parliament) on 14 June 1972 to manage the state’s commercial interests in the petroleum sector, was young and inexperienced.

Statfjords betydning for Statoil

Statfjords betydning for StatoilArve Johnsen, the first chief executive of Statoil, had ambitious plans for the state company. He made a joint approach with chair Jens Chr. Hauge to the centrist coalition government under Lars Korvald in 1973 to request 100 per cent of blocks 33/9 and 33/12 in PL 037.

The industry ministry, where Johnsen had previously worked as a junior minister, was dubious about that proposal. It took the view that even a 50 per cent holding for Statoil would be large, and worried that an excessive state holding would reduce the interest of foreign companies in the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). In addition, the ministry was concerned that giving too large a holding to Statoil, with its limited experience, would delay the process of exploring for and developing a possible field.

After a pause for thought, PL 037 was awarded to Mobil as operator, with 15 per cent, Statoil with 50 per cent, and Shell, Esso and Conoco with 10 per cent each. Four other companies shared the remaining five per cent.

The international oil crisis, erupting in the autumn of 1973 and persisting until the following January, created entirely new conditions. Global crude supplies came under threat, and an oil discovery in the politically stable North Sea became more attractive than ever. Oil prices were rising sharply, offsetting high development costs.

Discovery and start-up

Drilling in PL 037 proved successful. The initial well on block 33/12 found oil in March 1974. That was the first exploration drilling undertaken by Mobil Exploration Norway Inc on the NCS.

After the field had been declared commercial, the Storting approved the development of one of the world’s largest and most demanding offshore oil fields of the day on 16 June 1976. It lay in 100 metres of water, and about 15 per cent of it extended into the UK sector of the North Sea.

The Statfjord development meant Statoil hit the ground running. One consideration was its 50 per cent holding. Equally important was that the company was to be educated by Mobil to take over the operatorship after 10 years. Statoil would gradually build up a shadow organisation and ultimately acquire full responsibility as an operative company.

This organisation grew initially to several hundred people and subsequently to almost a thousand.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Statoil was initially dependent on appropriations from the Storting. Such capital inputs were proposed and administered by the Ministries of Petroleum and Energy and of Finance. The company soon bypassed Hydro’s oil division in terms of experience. Although the latter had been in position on the NCS since the first licensing round in 1965, its petroleum organisation was small and worked mostly on managing licence interests, including one in Ekofisk.

Statfjords betydning for Statoil

Statfjords betydning for StatoilStatfjord A began production on 24 November 1979, followed by the B and C platforms on 5 November 1982 and 26 June 1985 respectively. Construction and start-up of these installations was a story of technology progress characterised by cost overruns, which were eventually offset by rising oil prices.

This field created an economic base for Statoil which was crucial for the company’s further development. The field not only allowed it to build up the necessary expertise, but also acquired a symbolic significance for its status and corporate culture.

Statfjord has exceeded all expectations. Its outstanding sandstone reservoir has production properties on a par with the best oil fields in the Middle East, and it has yielded a rich return. Ekofisk may have been the first Norwegian oil

discovery and the largest in terms of resources in place when it was proven in 1969. But Statfjord has outperformed the chalk reservoirs in the Ekofisk area and other fields for ease of production.

On 16 January 1987, the best day in its history, it yielded 850 204 barrels of crude. No other Norwegian oil field has come close to that record. By comparison, Statfjord was expected to average 21 000 barrels of oil per day in 2011.

Statpipe

Constructing the Statpipe gas line was a strategically important move for Statoil in relation to Statfjord. Although Mobil was still operator for the latter, Johnsen secured acceptance for treating the pipeline as a separate project led by Statoil. The company devoted more than NOK 100 million up to January 1979 on studies conducted by various sub-contractors.

It was decided to land oil from Statfjord by offshore loading into shuttle tankers. The Storting then resolved in 1981 that the gas would be brought ashore by pipeline to Kårstø north of Stavanger for processing before onward transport in another pipeline to Germany.

Work on laying this Statpipe system began in 1983. Two years later, in October 1985, Norwegian gas began to flow via the mainland to continental Europe. Crossing the deep Norwegian Trench which runs just off Norway’s western coast with two pipelines was a technological achievement and a milestone in Norway’s petroleum history.

Overmighty?

Mobil agreed to train Statoil up in order to secure the largest possible holding in the promising Statfjord licence. Leading the development and operation of one of the largest and most challenging oil fields up to that time was regarded as

strategically important. But the US company did not really want to surrender this position after 10 years, as the licence specified.

Under the leadership of top executive Alex Massad at Mobil’s New York head office, it launched a campaign to retain the operatorship. All ambiguities in the licence terms were exploited, and an active lobbying campaign was pursued to achieve political support for the Mobil view.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik 2009: 106-110.

Few oil issues have caused greater dissension in the Storting. As one of its first actions, the Conservative government under Kåre Willoch which took office after the 1981 general election withdrew a proposal by Gro Harlem Brundtland’s outgoing Labour administration to exercise the operator transfer option.

But this move was not entirely straightforward, since Statoil was wholly state-owned. It meant acting against one’s own company. The debate sharpened in 1982, when Johnsen pointed this out and claimed that the government was acting contrary to the national interest. Willoch responded by asking whether the country was run by the government or by Statoil.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Offshore.no, 23 November 2009. “Oljefundamentet 30 år”. But the operatorship changed in the end.

This affair showed how powerful Statoil had become in the space of a few years. The politicians wanted to secure better control over the cash flow it generated, and launched the state’s direct financial interest (SDFI) on the NCS in the mid-1980s.

Under this reform, Statoil had to surrender part of its holdings to direct government administration. But Statfjord was excluded from the scheme, and the company retained its original 50 per cent stake in the field. That was crucial for winning Labour support for the change.

The huge value created by Statfjord has been crucial for Statoil’s development as an oil company. Without the field, it would have been a very different enterprise. Statoil would in any event have taken much longer to develop into a fully competent operator with a high level of production, as it did during the first decades of Statfjord’s history.

støping av a-en,

støping av a-en,

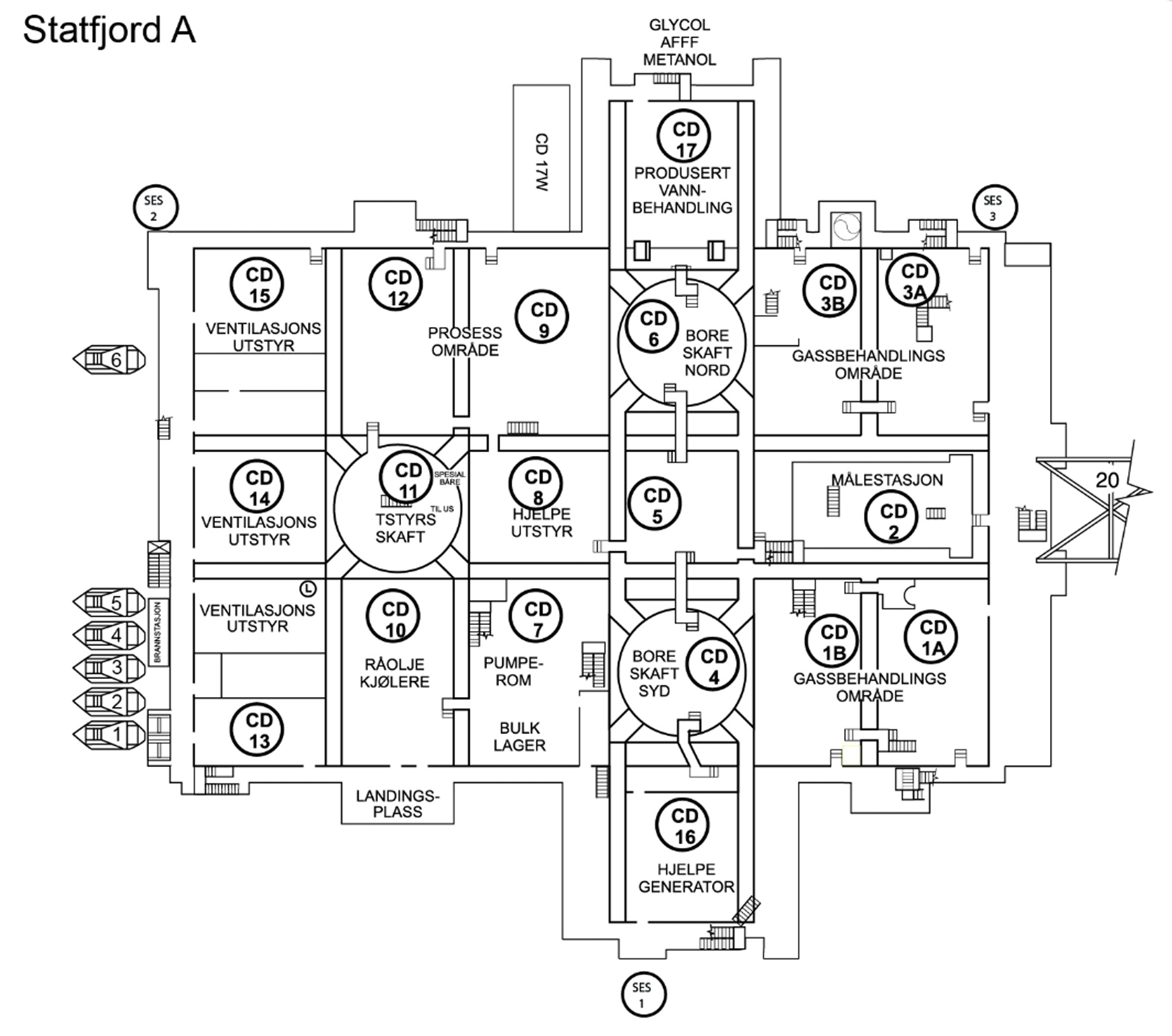

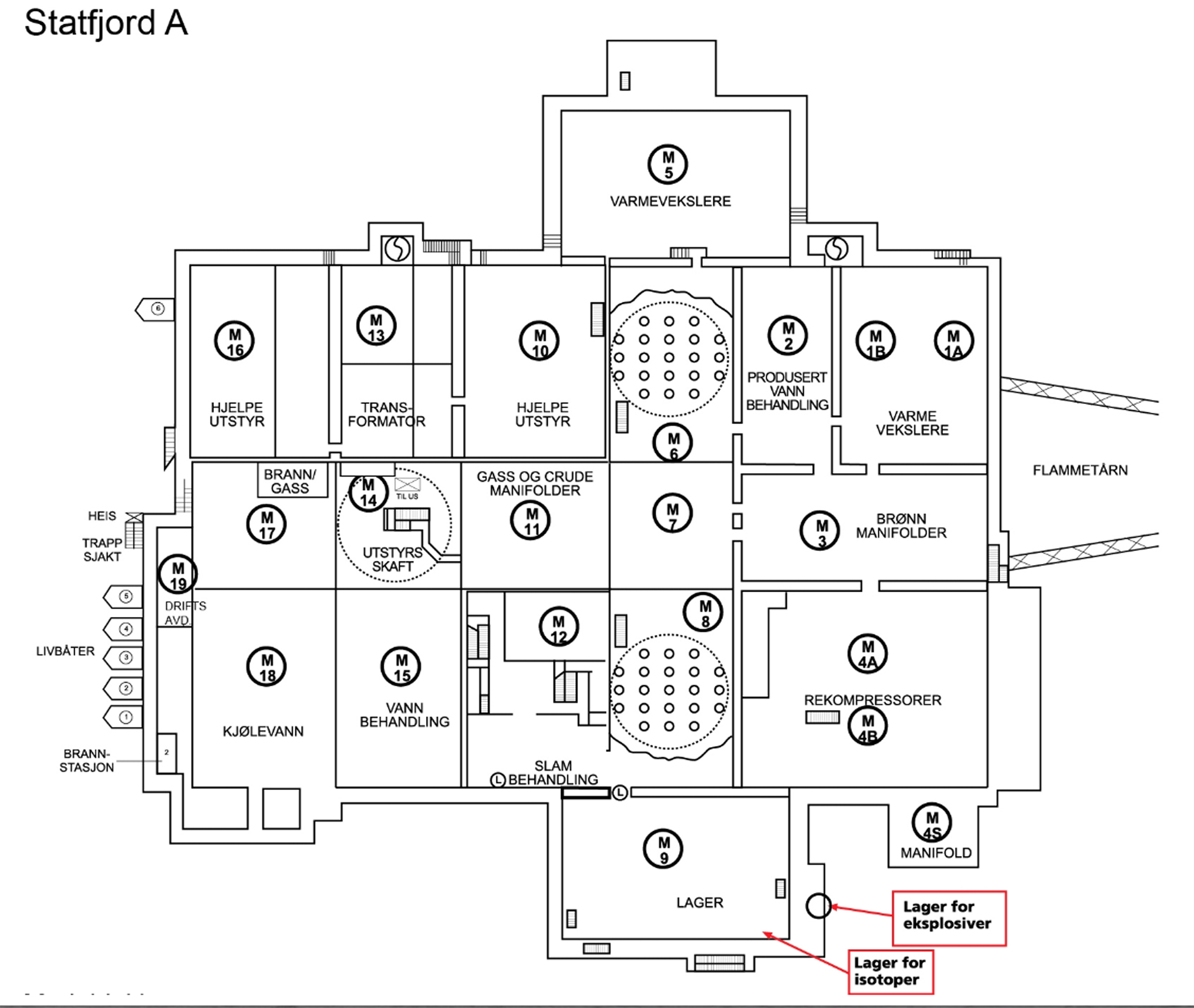

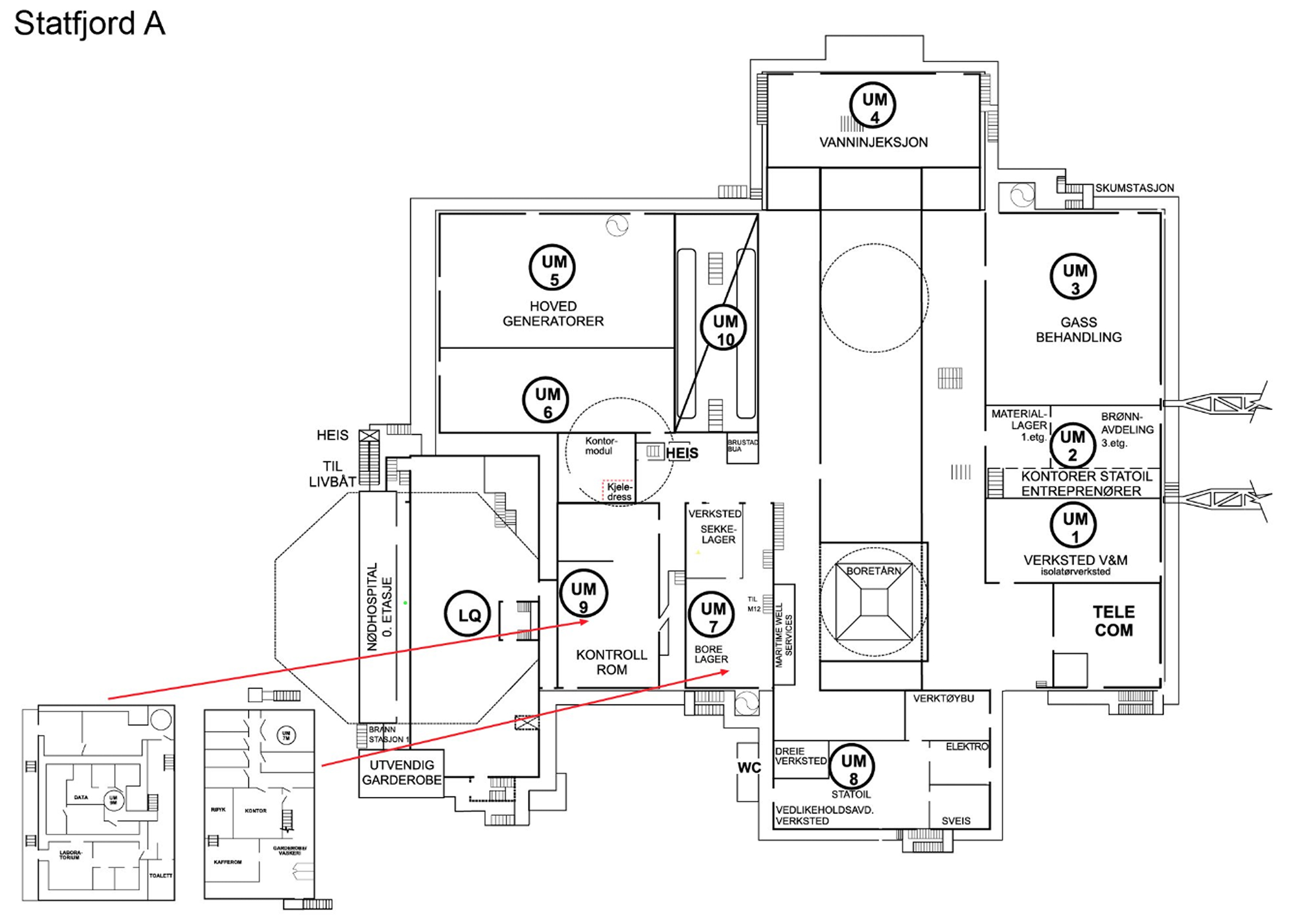

Statfjord A,

Statfjord A, Statfjord A,

Statfjord A, Statfjord A,

Statfjord A, Bygging av A-dekket,

Bygging av A-dekket, støping av a-en,

støping av a-en, Statfjord A,

Statfjord A, Statfjord A,

Statfjord A,