Statfjord subsea

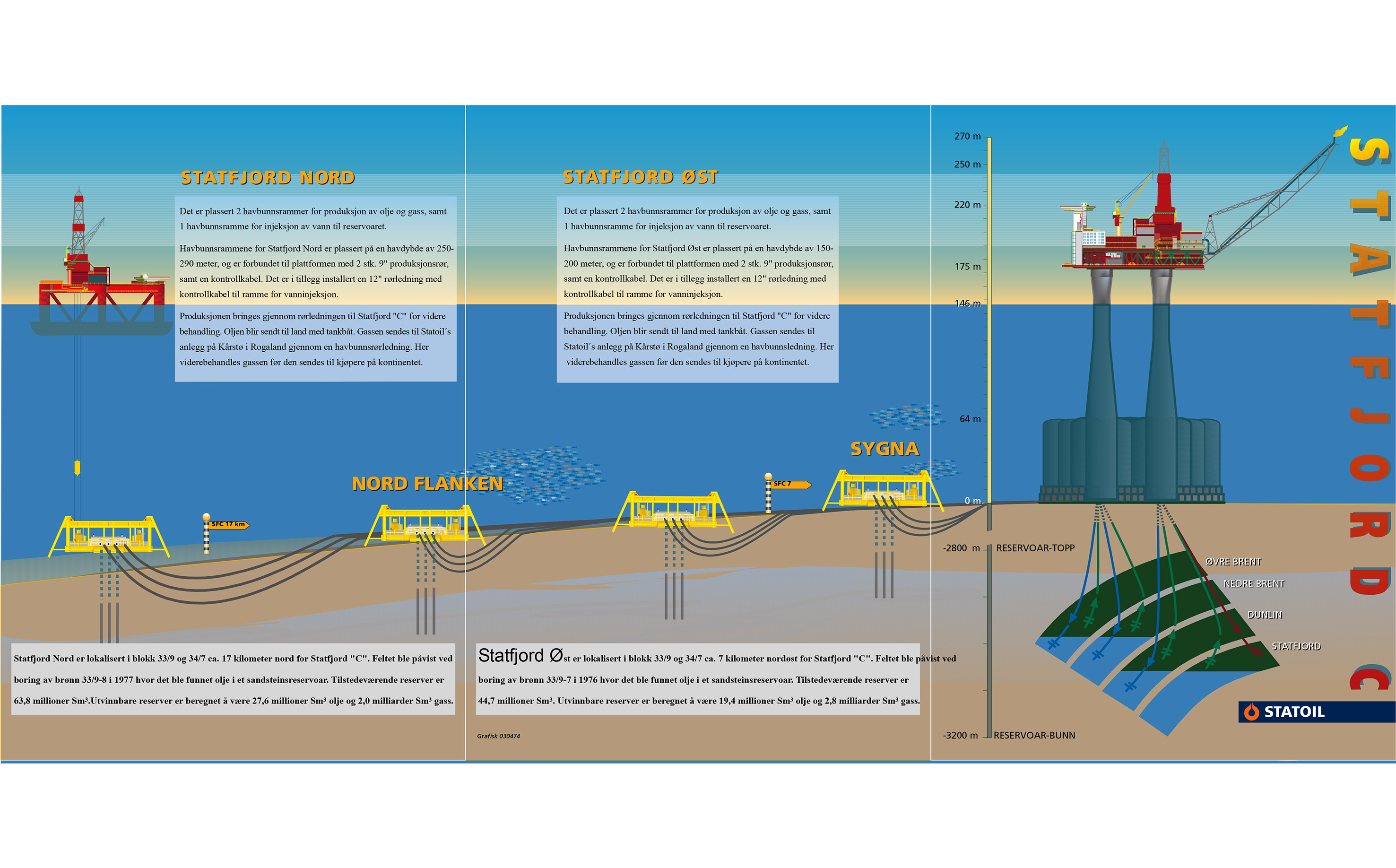

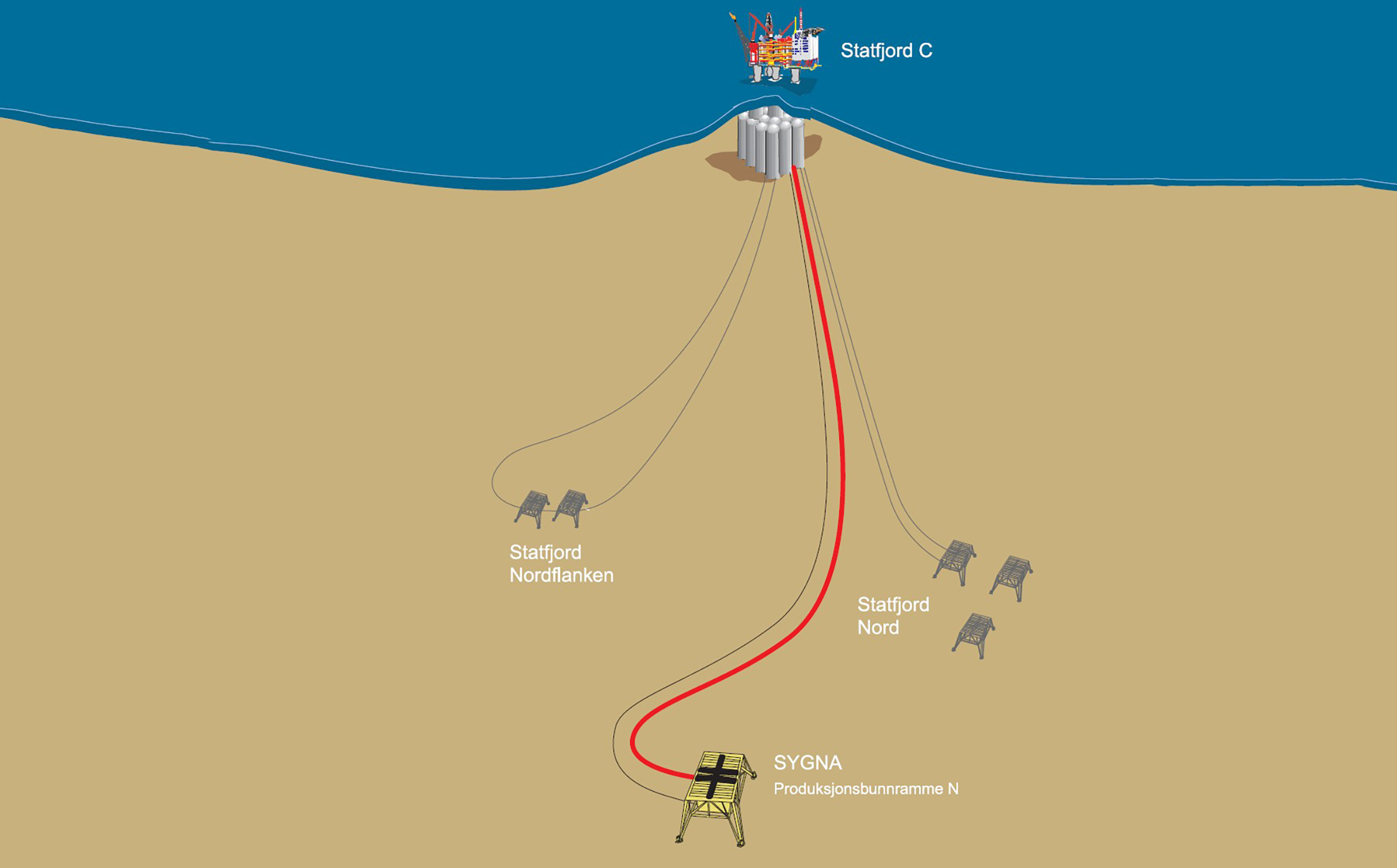

A discovery was made five kilometres north-east of the present site of Statfjord C in 1976, and another the following year 22 kilometres to the north. Dubbed the Statfjord satellites, their development represented a departure from the Condeep platforms used on the main field.

More about geology and subsea

close

Close

Statfjord subsea,

Statfjord subsea, statfjord satelitter, forsidebilde, illustrasjon, Statfjord subsea

statfjord satelitter, forsidebilde, illustrasjon, Statfjord subsea Produksjonsstart Sygna, forsidebilde, historie, Statfjord subsea

Produksjonsstart Sygna, forsidebilde, historie, Statfjord subsea