Offshore loading versus pipeline transport

Both optionswere highly controversial. One dispute concerned where the gas was to be landed in Norway. Another arose because many politicians and Statoil personnel believed that the oil should also be piped to land. Offshore loading was viewed as an interim solution until the necessary pipeline could be laid. But that was not how things turned out – oil has been loaded into shuttle tankers on Statfjord throughout the field’s producing life.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lindøe, 2009: 9.

Lessons from Ekofisk and Frigg

The question of landing oil and gas in Norway had a history extending back to the royal decreeof 9 April 1965, which laid the groundwork for the first Norwegian offshore licensing round in that year. This specified that: “Should the King find itrequired by the national interest, he can determine that petroleum products are wholly or partly landed in Norway.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Royal decree of 9 April 1965, section 33.

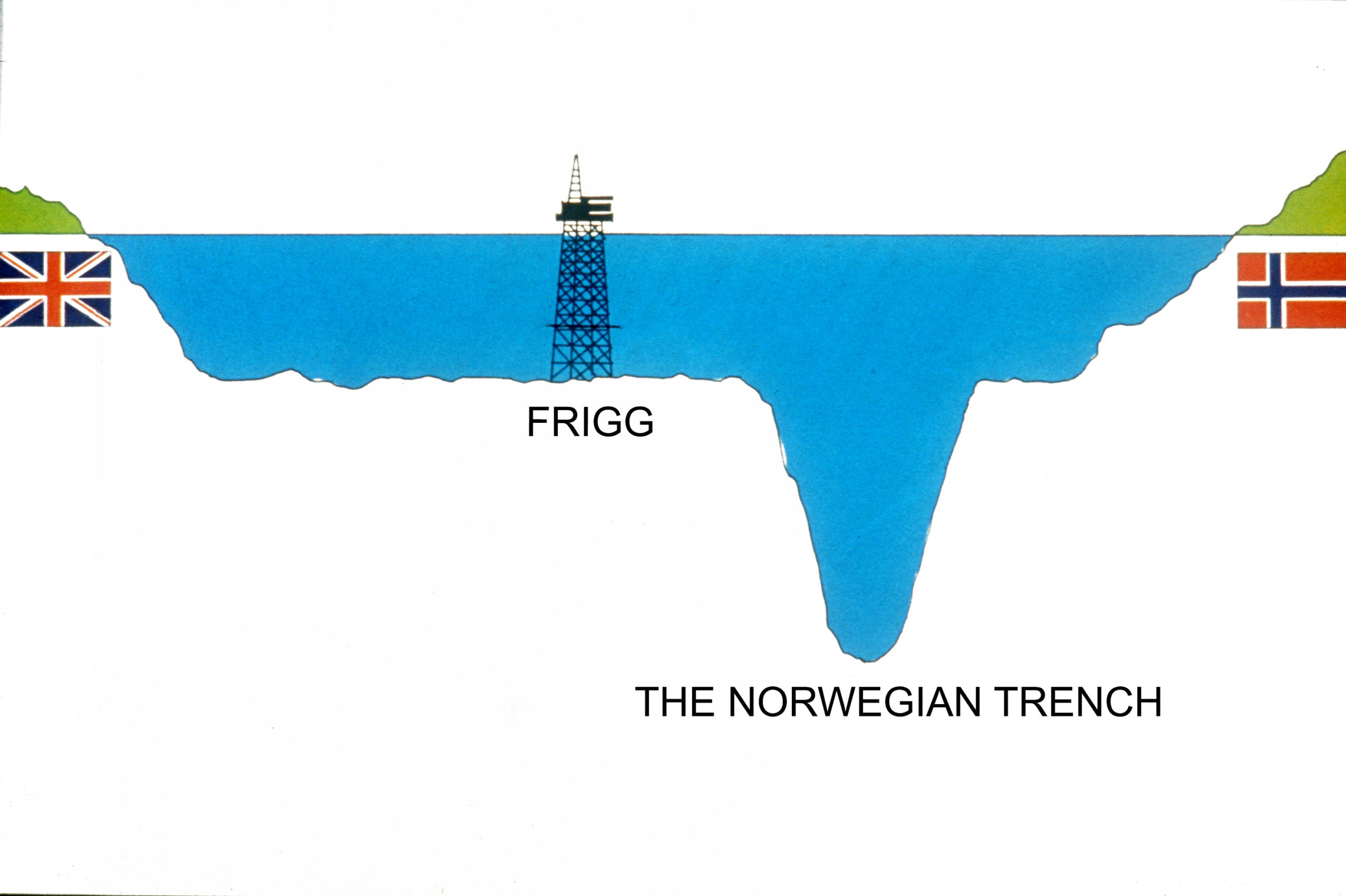

Nobody at the time knew how this was to be accomplished in practice. Oil exploration had barely started. As a result, it was not until gas and light oil had been proven in the Cod field during 1968 that a commission was mandated to assess opportunities for landing oil by pipeline in mainland Norway. Even though Cod proved too small for commercial production, the commission presented its report. This found that the deepwater Norwegian Trench running just off the coast of south-western Norway would be an obstacle to bringing oil and gas ashore by pipeline.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Kvendseth 1988, p 22.

Da det store Ekofisk-funnet ble gjort i 1969, reiste problemstillingen seg for alvor. Operatøren Phillips ønsket å legge rørledning direkte til markedene til Storbritannia eller kontinentet. Det viktigste motargumentet mot rørledning til Norge var fortsatt problemene med å krysse den 370 meter dype Norskerenna, noe Phillips hevdet var umulig med datidens teknologi.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ibid.: 59–60.

The issue first became serious when the major Ekofisk discovery was made in 1969. Operator Phillips wanted to lay a pipeline directly to the markets in the UK or continental Europe. The most important argument against laying pipelines to Norway remained the 370-metre-deep Trench, which Phillips claimed could not be crossed with existing technology.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NOU 1972, 15. Ilandføring av petroleum.

In August 1970, the Industry Ministry appointed the Ekofisk commission to consider the question in greater detail. The political desire to land petroleum in Norway was meanwhile enshrined in the“10 oil commandments” formulated by the Storting’s standing committee on industry in 1971. According to the sixth of these policy principles, “petroleum from the Norwegian continental shelf must as a main principle be landed in Norway, except in those cases where socio-political considerations dictate a different solution”.

The conclusions in the Ekofisk commission’s report, presented as Norwegian Official Report (NOU) 15 of 1972 on landing petroleum, were reached in line with this desire. Unlike Phillips, they found that crossing the Trench with a pipeline was technologically feasible, but would demand a good deal of research and development work before it could be implemented. That might postpone the start to production from Ekofisk by one-three years.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NOU 1972, 15. Ilandføring av petroleum .

Such a delay was undesirable for the operator, the other licensees or the government, which would lose revenues during that period. Phillips was thereby permitted to lay an oil pipeline to the UK and later a gas pipeline to Germany.

Bøyelasting eller oljerør?,

Bøyelasting eller oljerør?,History repeated itself when the Frigg gasfield came to be developed. Yet another official commission was appointed to assess opportunities for crossing the Trench with a pipeline.[REMOVE]Fotnote: NOU 1974, 40. Rørledninger på dypt vann. Even before this body had completed its work, however, the decision was taken to lay a pipeline to Britain. Thirty-nine per cent of the field lay in the British sector of the North Sea, and the UK had already decided to pipe its share of production to Scotland.

To avoid the UK tapping Norway’s share of the reserves, development on the Norwegian side had to be coordinated with the British plans. The Storting approved a plan in 1973 to lay a Norwegian gaspipeline parallel to Britain’s.

Technological to pipelaying over the Trench were a fact, whether the politicians liked it or not. Among other constraints, divers would have to be able to descend to the relevant depths. Diving was essential for repairing damage to a pipeline during laying and operation, and for helping to position trenching equipment.

When the first report was written in 1970-71,saturation diving was in its infancy and it was only possible to descend to a depth of 117 metres. By 1973-74, dives were being made to 150 metres in connection with exploration on Britain’s Brent field and on Statfjord. But theTrench was more than twice as deep, and diving to 300 metres was more wishful thinking than reality at this time.

Offshore loading of Statfjord oil

Lastebøye på plass, forsidebilde, historie, Oljehandel, Bøyelasting eller oljerør,

Lastebøye på plass, forsidebilde, historie, Oljehandel, Bøyelasting eller oljerør,After Statfjord had been proven in 1974, it was developed by Mobil as operator and Statoil as the biggest licensee. Unlike the position on Ekofisk and Frigg, the government had a dominant equity holding in the field through Statoil. That ensured considerably greater Norwegian influence.

A condition of Mobil’s operatorship, more over, was that Statoil should be able to take over this role after a learning period. The first independent operative assignment Statoil undertook in connection with the Statfjord development was precisely to investigate opportunities for layinga pipeline across the Trench.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Nerheim 1996, p 39. A whole series of studies and reports was to follow.

Statoil initiated a transport study for landing oil and gas in the autumn of 1974, and the results were presented in November 1975. Two of the six options for landing oil involved a pipeline to Norway:

loading into tankers on the field

a 36-inch pipeline to Norway

two 24-inch pipelines to Norway

combined offshore loading and a 32-inch tie-in to the Ninian pipeline in the UK sector

a 36-inch pipeline to the Orkneys

a 36-inch pipeline to Shetland.

Sotra west of Bergen was identified by the report as the most relevant site for landing oil in Norway. But financial calculations indicated that pipeline transport would be much more expensive than offshore loading. The Statfjord licensees accordingly maintained that the study was more than sufficient to support a decision to use offshore loading on the field for its whole producing life.

The Storting debate on developing Statfjord and landing its output took place on 16 June 1976. Two loading buoys for oil were approved for the moment, at the same time as a development programme for laying a possible oil pipeline to Sotra was to be implemented by the Norwegian licensees.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norvik 1981.

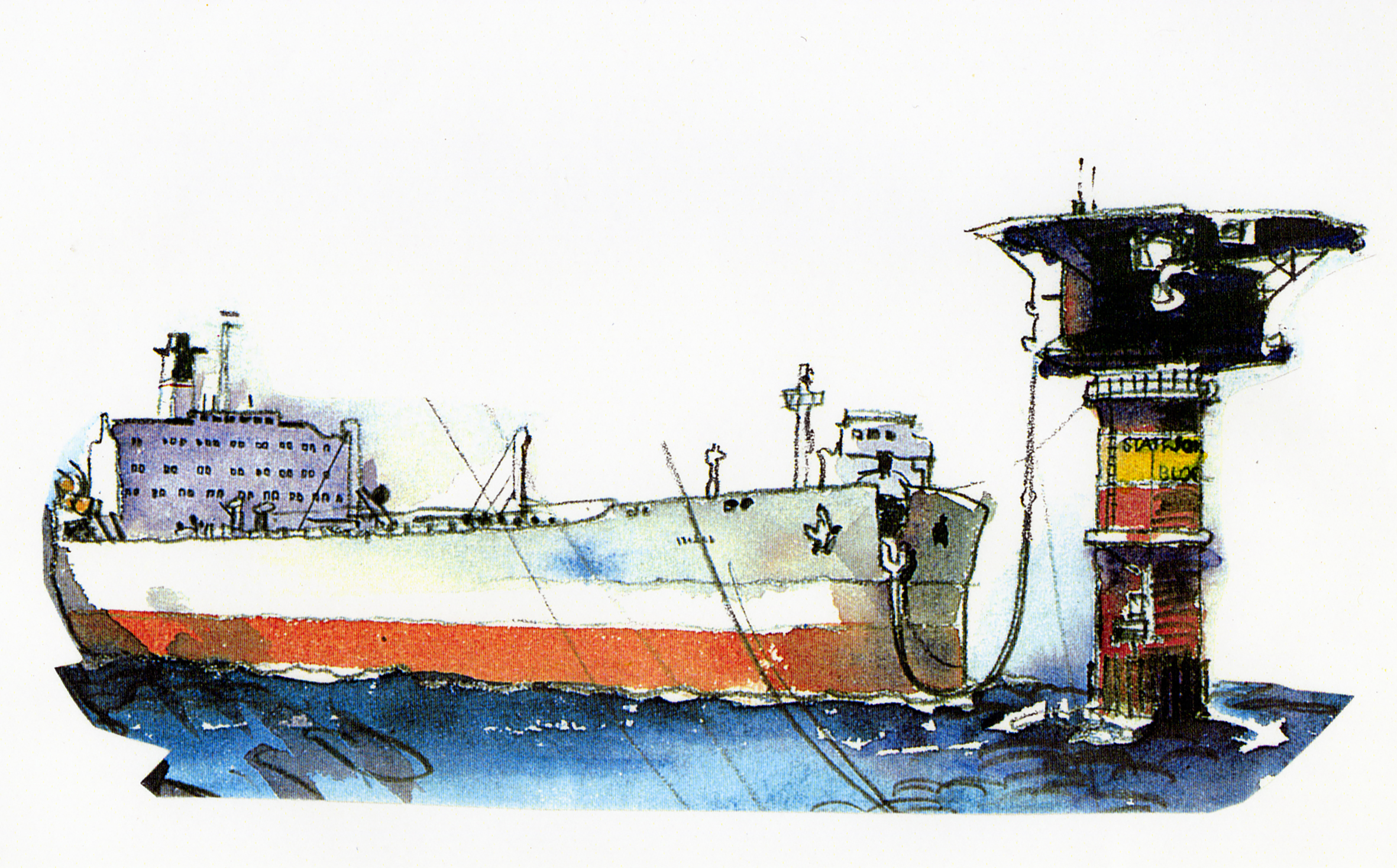

While this study was under way, an interim contract for offshore loading was entered into in August 1978. A limited partnership was created under the name K/S Statfjord Transport AS & Co to handle this job. Using chartered shuttle tankers, it was to be responsible for oil transport from Statfjord during the first development phase.

Statoil became the operator of this jointventure, which accordingly acquired an important role in offshore loading.[REMOVE]Fotnote: KS Statfjord Transport AS & Co had the same partner compositionas the Statfjord Unit, involving 12 companies. Lindøe 2009. p 20. The Polytraveller tanker from Norway’s Einar Rasmussen shipping company was the first vessel to the chartered, and lifted the first cargo from Statfjord on 9 December 1979. Sisterships Polytrader and Polyviking were also dedicated to oiltransport from Statfjord.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Lindøe 2009. p 20.Ready in March 1979, the Statfjord unittransport evaluation report was based on the studies conducted by Statoil and Mobil on pipeline transport and offshore loading respectively.

Statoil’s part of this work focused on an oilline to Sotra,[REMOVE]Fotnote: The full title of the study was the Statfjordtransportation system project. and concluded that it was technically feasible to lay and operate a pipeline from Statfjord across the Trench, via Hjartøy in Øygarden local authority, to a terminal at Vindenes in northern Sotra. It would be 207 kilometres long, including 24 kilometres over land. But further technical development and testing were needed before a pipeline could be laid in 300-350 metres of water.

The Mobil study showed that offshore loading yielded the lowest investment and operating costs. The difference from a pipeline was estimated at NOK 6 billion. Such additional spending could not be borne after all the cost overruns when building Statfjord A, since estimates of recovery from the field had been reduced at the same time. Transport by shuttletanker would be the cheapest option both for the immediate future and in the long term.

An application for exemption from the general rule of landing in Norway was submitted by the Statfjord licensees to the recently established Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. On the basis of profitability, the group unanimously recommended offshore loading for the whole lifetime of the field.

The Storting approved this solution on 23 May 1980, and offshore loading was thereby chosen as the permanent solution for transporting oil from Statfjord.

Sources

A North Sea gas gathering system . Joint report by British Gas Corporation and Mobil North SeaLimited, London, June 1980.

Gjerde, Kristin Øye and Helge Ryggvik. North Sea divers in Norway, 2009.

Helle, Egil (ed). Olje og energi i ti år 1978-1988. Oslo, 1987.

Hellem, Rolf. Oljen i norsk politikk . Oslo, 1974.

Johnsen, Arve. Norgesevige rikdom. Oslo, 2008.

Kindingstad: Norwegian Oil History ,Stavanger, 2002.

Kvendseth, Stig: Giant Discovery. A History of EkofiskThrough the First 20 Years. 1988.

Lindøe, John Ove. From Sea to Shore. Stavanger, 2009.

Nerheim, Gunnar. En gassnasjon blir til, Oslo, 1996.

Norvik, Harald. Ilandføring av Statfjordgass og muligeoppdrag for norsk industri . Speech, NPC, 26 February 1981.

NOU 1972, 15,«Ilandføring av petroleum».

NOU 1974, 40,«Rørledninger på dypt vann».

Stafsnes, Tor. Ilandføring av petroleum fra Statfjord: analyse av en iverksettingsprosess . Bergen, 1984.

Report no 90 to the Storting (1975-76): Om utbygging og ilandføring av petroleum fra Statfjord-feltet og om en samlerørledning for gass.