The loading buoys on Statfjord

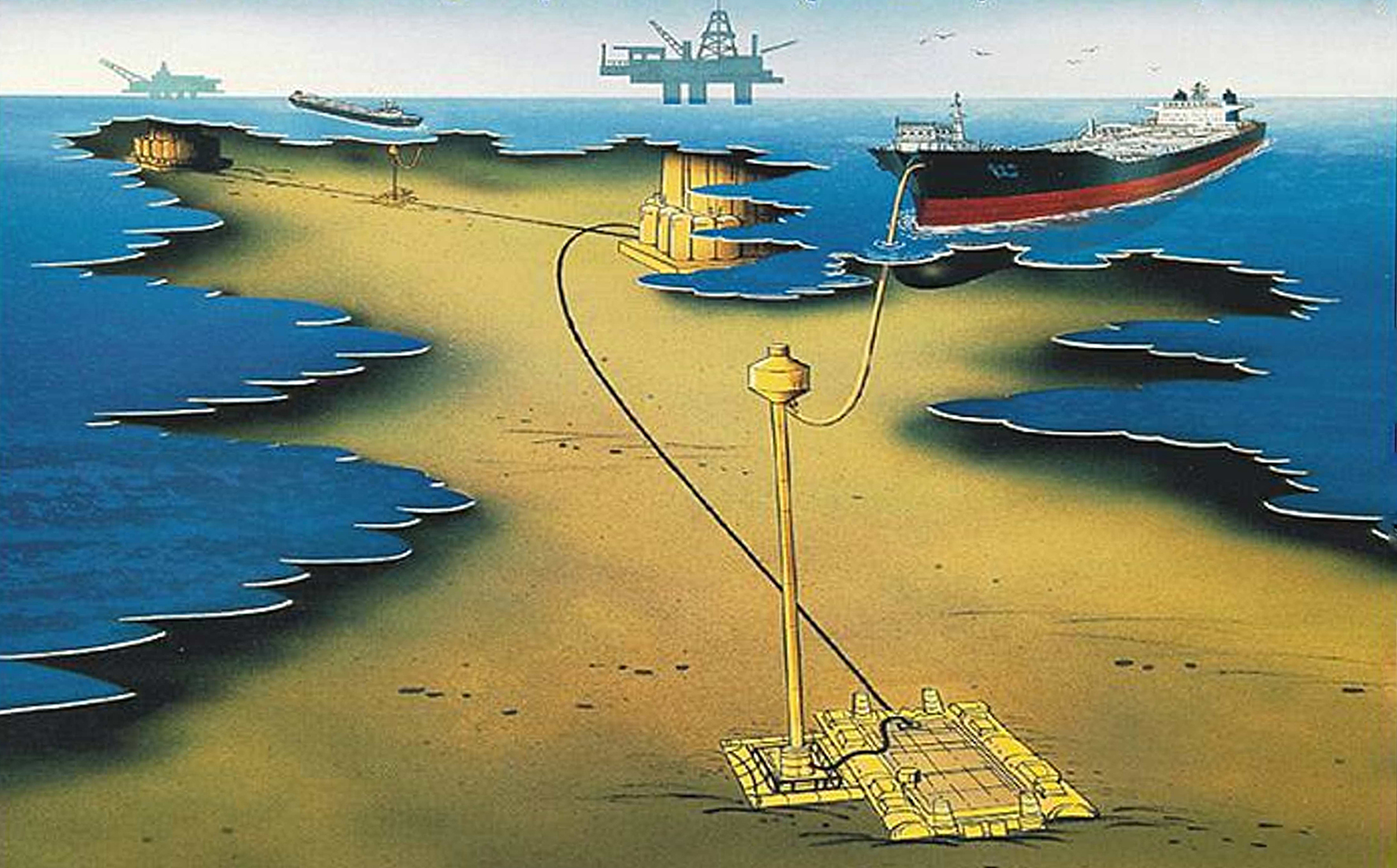

The Norwegian Statfjord licensees had to find solutions for transporting the huge volumes of oil and gas involved. While the gas went by pipeline to Germany, the stabilised crude oil was exported by specially equipped shuttle tankers to refineries and terminals throughout northern Europe. Such offshore loading failed to comply with the “10 commandments” of Norwegian petroleum policy, which said that all the country’s oil and gas production should be landed in Norway. That made it difficult to approve the system.

More about further development

close

Close

Stortingsvedtak om Statfjord B og C, historie, Den første planen – Statfjord B

Stortingsvedtak om Statfjord B og C, historie, Den første planen – Statfjord B Lastebøyene på Statfjord,

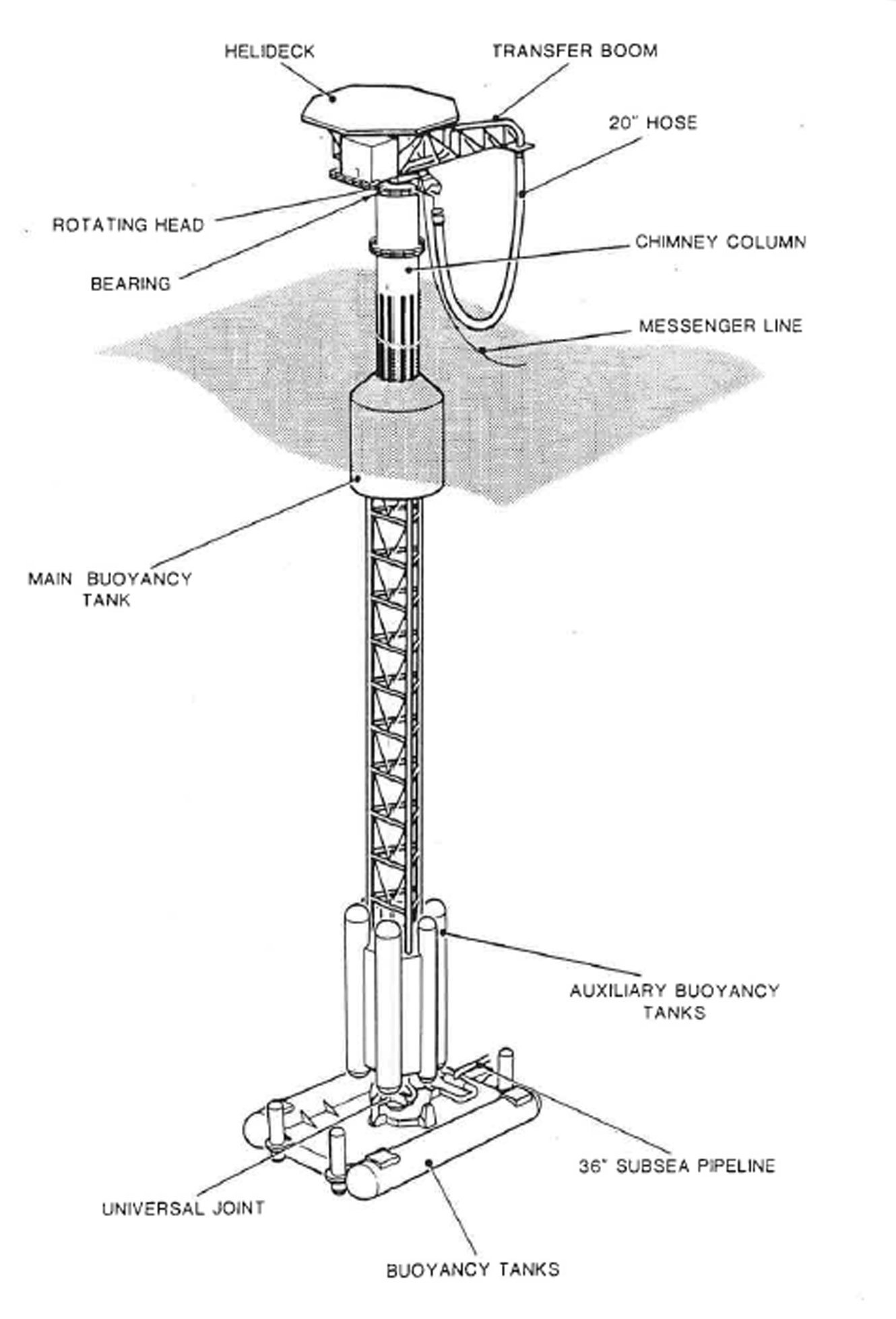

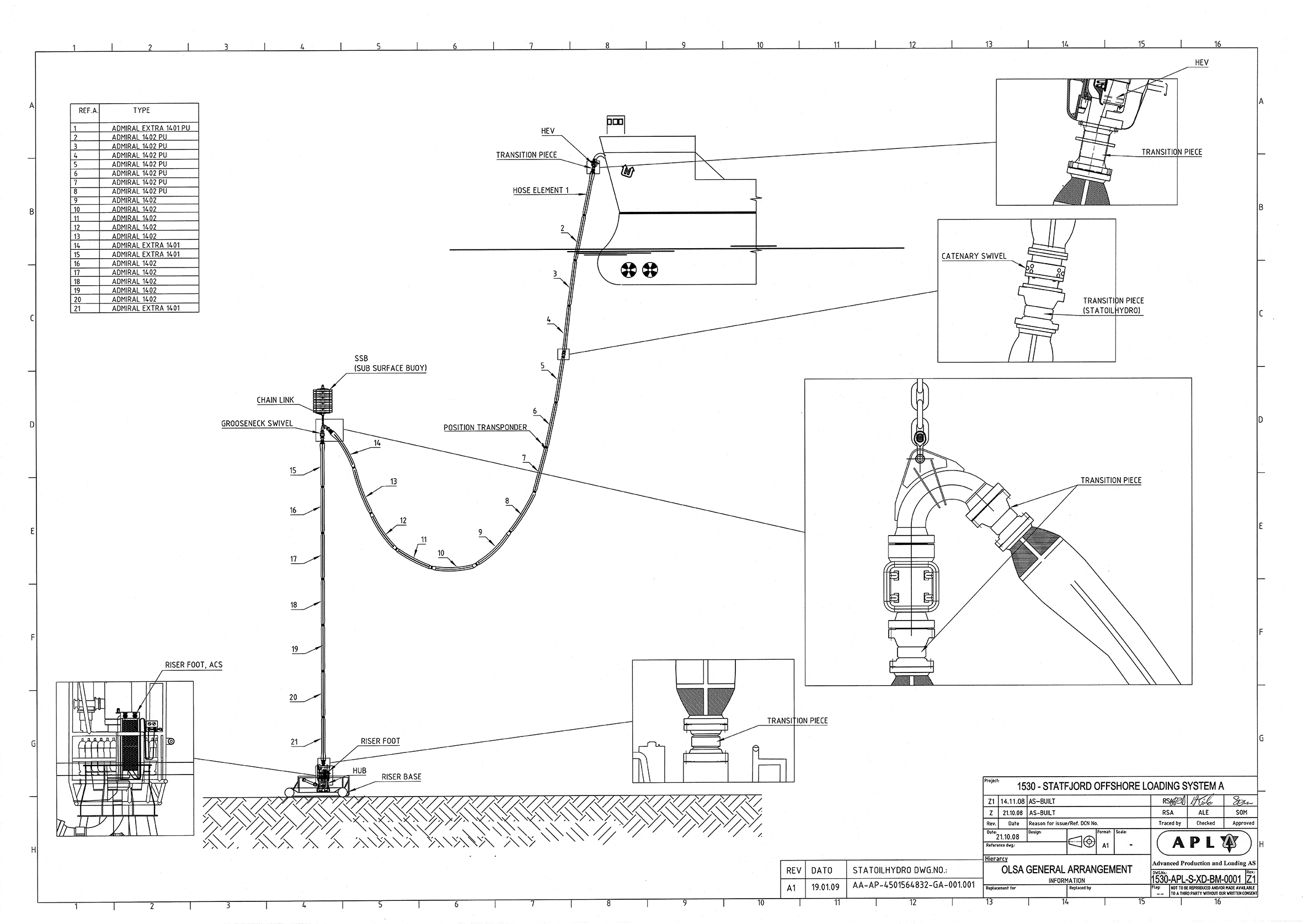

Lastebøyene på Statfjord, lastebøyer ulike alternativ, illustrasjon, engelsk, Lastesystemet UKOLS på plass, lastebøyene på statfjord,

lastebøyer ulike alternativ, illustrasjon, engelsk, Lastesystemet UKOLS på plass, lastebøyene på statfjord, Utskifting av lastebøye, historie, forsidebilde, lastebøyene på statfjord,

Utskifting av lastebøye, historie, forsidebilde, lastebøyene på statfjord,