The work camps

Byggestart for A-en, historie, forsidebilde,

Byggestart for A-en, historie, forsidebilde,This initiated a new industry in the Hinnavågen district on the outskirts of Stavanger. It began with the Condeep-type concrete gravity base structure (GBS) ordered by Mobil to support the topside for an oil and gas platform on Britain’s Beryl field. While Beryl A and eventually also Brent A – again for the UK continental shelf – were under construction, work also began on casting the GBSs for Statfjord A and Brent D in the Hinnavågen dry dock.

Building four such massive structures meant that several thousand personnel had to be recruited from all over the place. Norwegians, Swedes, Finns and other nationalities flocked to the construction sites in Stavanger and at Stord further north, where the Statfjord A topside was fabricated and outfitted. But the question was where all these incomer workers to live and how to provide for them.

Incomer labour in Stavanger

brakkebyene,

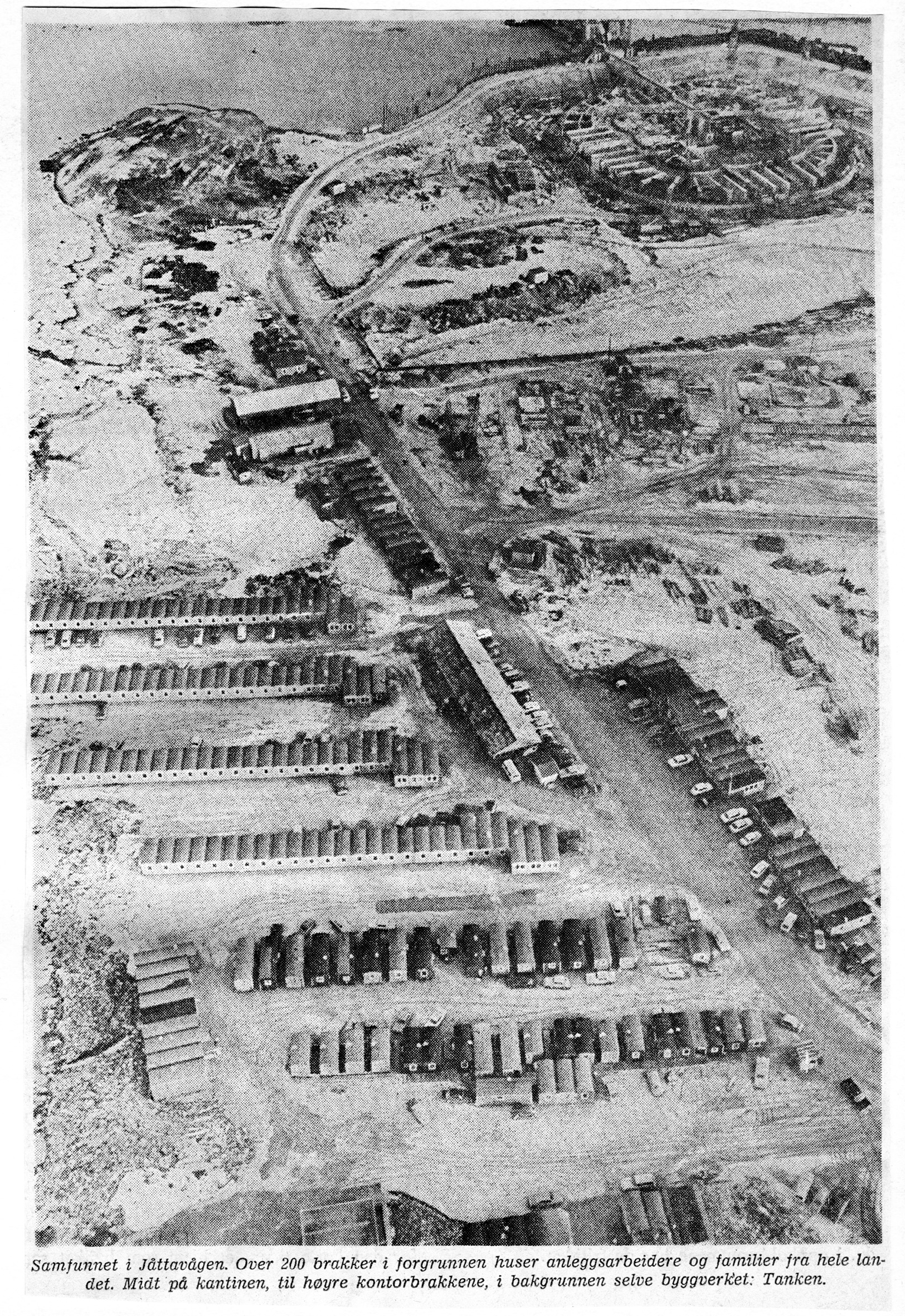

brakkebyene,Hinnavågen was a full-bloodied construction site during 1973-77. Not only were four large Condeeps being built in the bay and out in the fjord, but a large work camp had also been established on land to accommodate several thousand incomers. The same phenomenon occurred at Kjøtteinen on Stord, where the Stord Verft yard was located.

Many of the work camp residents in both places were employed on Statfjord A as well as on the other platform structures which lay in the Gands Fjord outside Hinnavågen or Digernessundet off Stord. Workers who could not be accommodated in the camps were packed together on hotel ships berthed at the quays.

During the busiest period between 1974 and 1976, an average of 800 people at a time occupied the temporary accommodation in Stavanger, but few worked there for more than six months. Over the whole period, 3-4 000 people were housed in the work camps and the hotel ships.

The work camp had become twice the size envisaged when construction companies A/S Høyer-Ellefsen and Ing F Selmer A/S applied to the city council for permission to lease the Hinnavågen area in order to “build offshore projects for the oil industry”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger. Stavanger. A/S Høyer-Ellefsen and Ing F Selmer A/S joined forces with Furuholmen to found the Norwegian Contractors (NC) joint venture, which was responsible for casting the Condeep GBSs.

Together with the Aker group, these two companies had won the order to build and outfit Beryl A as the world’s first concrete production platform. They submitted a request in 1973 to the city council for permission to fill in the Hinnavågen bay in order to create a dry dock, and to use the flat ground behind for warehousing and a work camp.[REMOVE]Fotnote: City of Stavanger, executive board case 1975 A, 7.9. 1972. A/S Høyer-Ellefsen and Ing F Selmer A/S had applied to the council as early as 1972 to lease “the areas with adjacent seabed at Dusavika or Hinnavågen, Stavanger, and moreover anchorage at Hillevåg to build offshore projects for the oil industry“. But NC failed to win contracts at the time and the issue was postponed.

At that time, the companies envisage a maximum requirement of 200 beds.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger: 65. This proved to be a very substantial underestimate. The camp reached its peak occupancy in the spring of 1975, with around 2 000 people temporarily quartered there and on three hotel ships berthed at the Hetland quay.

brakkebyene,

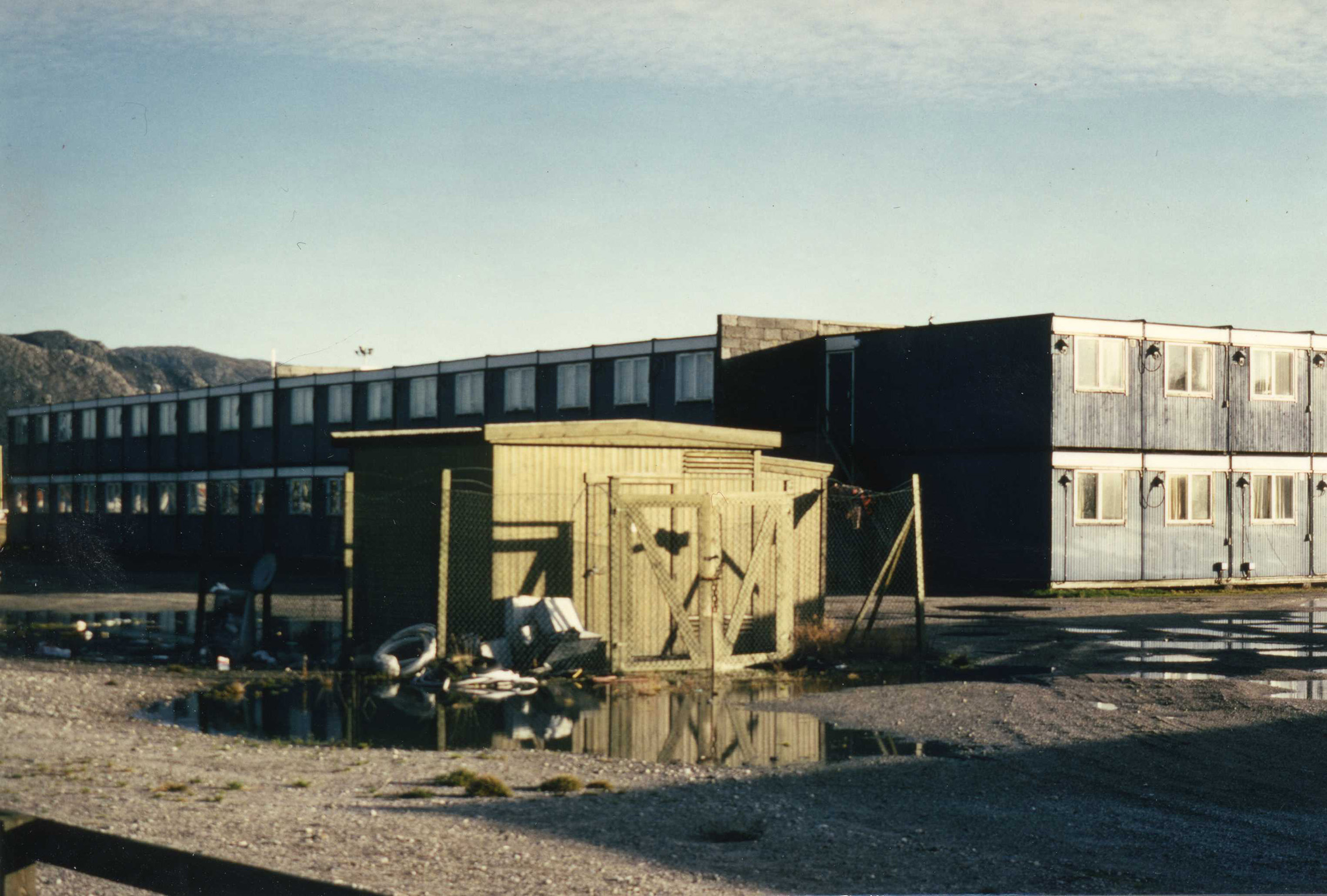

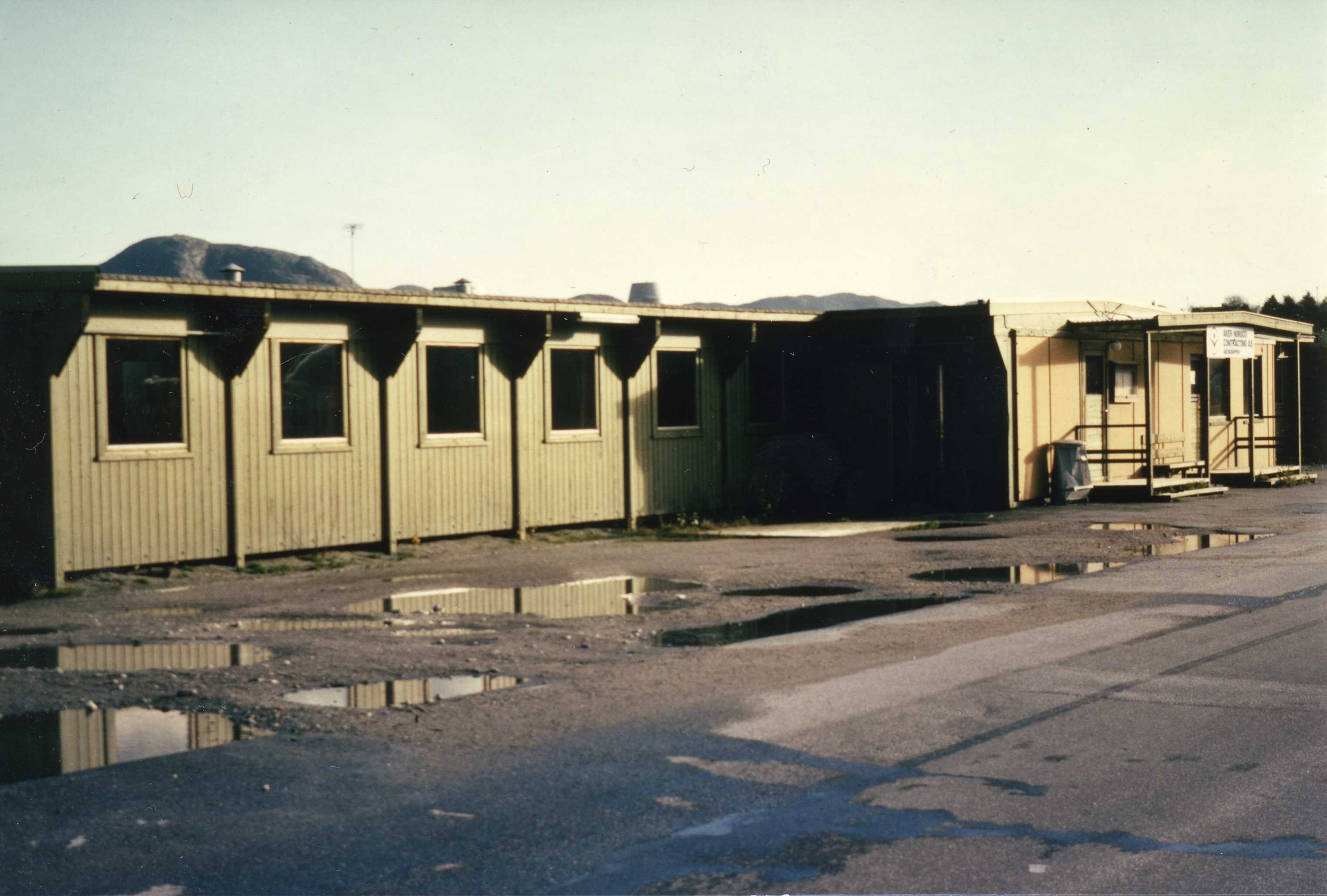

brakkebyene,A year later, the camp had a capacity of 950 people in 60 double – known as “combined rigs” – and single rooms. In addition, all available camping cabins, boarding houses and flats were occupied by incomers working at the facility. Built on former fields and an old rubbish dump overlooking the dry dock in Hinnavågen, the work camp comprised rows of temporary buildings spread around warehouses and temporary offices.

The Ekofisk tank had been cast at nearby Jåttåvågen a few years earlier, again by Høyer-Ellefsen and Ing F Selmer. Part of the area had thereby already been developed, but most of the original site was converted to recreational use after the tank had been completed. The dry dock became a marina. In order to launch new building projects, the whole area had to be redeveloped.

Local opposition

brakkebyene,

brakkebyene,The council’s consideration of the application emphasised the opportunity to secure new industrial jobs for the city. But not everyone was pleased to see Hinnavågen converted into a giant construction site, and residents of Hinna and Jåttå formed an action committee to oppose the scheme.

They were not only negative to the plans, but also wanted certain conditions to be laid down in advance. These related to sewage facilities, Hinna’s Vaulen bathing site and working hours. The council’s executive board responded to certain of these demands.

It instructed the contractors to ensure that all sewage problems in the bay had been overcome by the time the first Condeep base section was ready to be towed out of the dry dock – in other words, within a year. The bathing site had to be retained and protected as well as possible, which meant that the cement mixing plant had to be moved as far to the south as possible. The council also accepted that work would be confined to the hours from 06.00 to 23.00 with exceptions for some jobs – particularly slipforming and repairs.

The action committee also wanted the issue to be postponed and the construction period to be confined to a maximum of two years. These demands were rejected by the council, which gave the contractors a lease for five and a half years and allowed the work to begin immediately.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 6 August 1973. “Uklarhet om spuntveggen”. and Stavanger Aftenblad, 9 August 1973. “Det blir Hinnavågen på visse betingelser”.

In its application to the city council to build temporary accommodation for 200 incomer workers, no account was taken of the fact that the Aker group, which was to perform the mechanical outfitting of the GBS, would also need a large labour force.

Norwegian Contractors (NC), as the GBS construction joint venture was called, was not the only company to accommodate personnel in the work camp. Aker Offshore Contractors (AOC) eventually had a big need to provide sleeping quarters for its own employees as well as sub-contractor personnel.

As the two main contractors, NC and AOC administered the camp jointly but were separately responsible for their own workers. This meant in practice that accommodation varied according to the employer company.

brakkebyene,

brakkebyene,That part of the camp occupied by NC’s personnel was divided into huts with 50 single rooms containing a bed, a cupboard, a desk and two chairs. There was no room for more. Eight hand basins, three showers and two toilets had to be shared. In addition came two day rooms, one at each end of the hut, with TV and armchairs. One of these rooms was supplied with newspapers.

Food was free in the canteen for people working for NC or its sub-contractors, but the steelworkers employed by Aker had to pay for their own meals. They were given a subsistence allowance instead.

In a survey conducted by Per Stangeland at the Rogaland Research institute in 1975-77, perceptions of the food’s quality differed substantially between those who got “free” meals and those receiving an allowance – regardless of the size of the latter.

NC employees were almost unanimously positive to the food and the canteen, while the steelworkers who had to pay were almost equally unanimous in their criticism. Although the two groups each had their own canteen, the food in both was prepared by the same catering company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger. Stavanger: 170.

But the organisation of meals was not the only employer-related difference. NC personnel had access to a gym, with weights, wall bars, rowing machines, table tennis and a squash court. They also had a ramp they could use to fix their cars.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger. Stavanger: 158. The steelworkers, by contrast, had slot machines in the canteen as their only leisure activity. A kiosk serving the whole camp was open from 12.00 to 22.00.

White-collar workers were treated rather differently. Their hard hats clearly identified them, they had a separate pay system and different accommodation. Most of them resided in boarding houses, and they had their own canteen. One of the huts was also reserved for them, with their own chef and different equipment from in the leisure accommodation for the ordinary workers.

Leisure time

So there was not much to do. A soccer pitch only appeared in 1976. The days were largely spent working, eating and sleeping. Most of the incomers primarily wanted to earn money. TV, cards and reading dominated the evenings. “Work camp syndrome”, a state of lassitude and apathy, is a well-known phenomenon.

brakkebyene,

brakkebyene,Unlike many other construction sites, however, Hinna was only seven-eight kilometres from downtown Stavanger and bus services were good. According to some of the old-timers, this had both negative and positive aspects. The disadvantage was that it could be difficult to organise common activities and the environment in the work camp was therefore not as good as it might have been. Much of the social life was drawn out if it.

But precisely the opportunities to escape from the site through a trip into town could have a positive effect. Restaurants, cinemas and the swimming pool were the most popular destinations. The many Finns at the camp were particularly keen to visit the sauna at the city baths. A sauna was only installed at the camp in 1976.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger. Stavanger: 171-172. Quite a lot of time was spent partying, and the Cobra nightclub became the place to meet in town for the Aker workers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Svein Jørpeland by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum.

The hotel ships

A number of the incomers lived on hotel ships, which were berthed at the site for two periods – February-June 1975 and October 1975-May 1976. These ferries had steel containers packed together on car and sun decks to serve as cabins. The corridors on either side were only a metre wide, and it was always semi-dark below deck. Each container had two rooms – a bathroom with shower and toilet and a bedroom with two bunks, although they were never occupied by more than one person at a time.

The ships offered a higher standard of accommodation than the work camp, but Stangeland says they were not popular. They were cramped, dark and oppressive. Their stuffiness was emphasised, and the normal work camp huts regarded as heaven by comparison. “This is a really shitty place,” one of the residents complained.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger. Stavanger: 161. Between 100 and 150 cabins on the ferry were also used and were – if possible – even worse.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stangeland, P., & Baldvinsdottir, A. (1977). Condeep : A platform construction site in Stavanger. Stavanger: 160.

Inhabitants

So who were the “inhabitants” of the work camp? Almost half of them were Norwegians, who largely came from other Aker companies or sub-contractors around the country. The remainder were mainly from Sweden and Finland, and had worked for long periods in Norway and Sweden before.

There was no organised import of foreign workers, even though Swedish sub-contractors brought their own personnel with them. As construction proceeded, however, the Swedes were increasingly phased out in favour of Norwegians.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Svein Jørpeland by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum. Few of these “travelling men” remained in Stavanger after the work was finished. They largely moved on to new construction sites.

Both workplace and work camp were male-dominated. No women worked on the GBS, but about 70 of them had jobs at the facility – 50 in the work camp and 20 on the hotel ships, which can be regarded as an extension of the site.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Leira, A. (1978). Kvinner på en oljearbeidsplass : En undersøkelse ved Condeepanlegget i Stavanger (Vol. Nr 8-1978, Sosialdepartementets sammendragsserie (rapportsammendrag : trykt utg.)). Oslo: Sosialdepartementet: 30.

The great majority of the women worked in service jobs, such as food, waitressing, laundry and cleaning. Some had more specialised posts, including secretaries, bookkeepers and switchboard operators, while a few had supervisory jobs such as canteen manager, cleaning supervisor and head cook. The last of these roles was usually played by men in the canteen kitchens. There were also two female crane drivers.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Leira, A. (1978). Kvinner på en oljearbeidsplass : En undersøkelse ved Condeepanlegget i Stavanger (Vol. Nr 8-1978, Sosialdepartementets sammendragsserie (rapportsammendrag : trykt utg.)). Oslo: Sosialdepartementet: 37.

Population growth at Stord

Brakkebyene, a-plattformen,

Brakkebyene, a-plattformen,Fabrication of the steel topside for Statfjord A began at Stord Verft in 1975. Building and outfitting this structure involved a lot of work, so the yard was in great need of additional labour. It was resolved in April 1976 to build temporary quarters for 100 workers at Naustvågen. The number of beds was increased to 450 in September, which again proved far from sufficient.

A number of hotel ships berthed, including North Sea ferry Leda, bought by the yard, as well as Kronprinsesse Märtha, Vikingfjord, Prince of England and Dana Sierena. None of these vessels were regarded positively.

“Work camp capacity was soon exhausted, and the yard had to hire more or less condemned ferries as accommodation,” the workers themselves recalled in the 20th anniversary publication about the union branch at Aker Offshore Partner.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bedriftsklubben Aker Offshore Partner. (1994). Bedriftsklubben Aker Offshore Partner 20 år : 1974-1994. Stavanger: Klubben: 10. “All the cabins were occupied, including those below the waterline. Ventilation and hygienic conditions were below par and dissatisfaction was great.”

In the spring of 1976, Mobil ordered the company to increase its workforce even further “in an attempt to compensate for the low productivity and slow labour build-up, so that the job could be completed on time and offshore work minimised,” as part I of the Cost Analysis for the Norwegian Continental Shelf (Kostnadsanlysen) put it in 1979.[REMOVE]Fotnote: A total of 2 377 workers and 342 consultants had been hired in to work at the new offshore yard in Kjøtteinen on Stord by 1 January 1977.

The Stord yard had 2 100 registered contract workers in September 1976, and this figure peaked at 2 719 the following January. That meant the population of the local authority had risen by a fifth. A mine site was converted into a work camp, and a small village of caravans also sprang up. Living conditions were wretched. People were packed together wherever space was available.

At one point, this led to a sit-down strike by the workforce. Those who took part were mainly workers hired in from abroad, but included personnel from other Aker companies – particularly Aker Verdal. The action was a protest not only against living conditions but also over working hours, changing room conditions, lack of leisure activities and discrimination against union officials. It was alleged that efforts were made to remove elected officers who called attention to deficiencies, and this was unacceptable to the workforce.

A number of conflicts broke out over working hours. Those who lived furthest away could not afford to go home every third week, because such travel was unpaid. They wanted to work as much as possible and then have a longer period off. The foreign incomers also earned better money and wanted to work more rather than hang around in Stord.

This meant in turn that the permanent workforce also had to work longer hours, which was not popular among those resident in Stord or with the unions. The locals wanted working hours which were better tailored to family life. That sort of thing breeds conflict.

Little provision was made for leisure activities, either in the work camp or in the local Stord community. But something was done. Table tennis, space for playing cards, TV viewing, darts and other activities were initially provided, but the equipment was damaged and both furniture and TVs thrown out of the windows by very inebriated workers, as Knut Grove recounts in his book about Stord Verft.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Grove, K., Heiret, J., & Stord jern- & metallarbeiderforening. (1996). I stål og olje : Historia om jern- og metallarbeidarane på Stord. Stord: Stord metall- og bygningsarbeider[e]s fagforening: 163-164.

This was a period of conflict, with much drunkenness and hullabaloo. But Statfjord A was towed out to the field on 3 May 1977, and Stord Verft had failed to win any new major contract. So the travelling men moved to new construction sites elsewhere. The work camp was already empty by the end of 1976.

Conclusion

Statfjord A was placed on the field in the North Sea by 1977. In Stavanger, NC had won new contracts – starting with Statfjord B and then Statfjord C. Eight other GBSs were to follow. It was not until 1993 that the last of the Condeeps left the construction site at Hinna. But things were never again the same as in 1974-79, when four large concrete structures were being built at the same time and 3 000 people were at work.

Stord, on the other hand, went from thousands of incomers in 1977 to lay-offs and dismissals the following year. The yard had waited for the next big project – Statfjord B – which never came. Read more under the title “The biggest single contract in Norwegian history“