Start-up, initial production and first cargo

E J Medley, chief executive of Mobil Norge, cut a ribbon in the Norwegian and American national colours to declare Statfjord A on stream before pressing a number of buttons in the control room to set production going.

Arve Johnsen, Statoil’s chief executive at the time, described the day as follows: “After sowing the seed, Statoil can now begin a long period of harvesting, and no industrial project on land can compare with the profitability of the Statfjord field.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Tidende. (1979). 13 December. Statfjord-olje for 100 millioner til Mongstad.

This was admittedly not the first time the A platform had produced oil. As always before an installation is brought officially on stream, trial output had taken place earlier.

Oil had first flowed from well A33 at 04.00 on 18 November, and the flare boom was ignited for the first time 30 minutes later – a sure sign that production was under way. This test operation lasted for 10-12 hours, before the oil was burnt off and the platform shut down again until normal production began six days later.[2]

Full control

Extensive preparations were made before the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD), on behalf of the government, gave the green light to start production. While the NPD was responsible for coordinating offshore safety, other official regulators were also involved.

The Norwegian Civil Aviation Authority approved flight conditions – in other words, take-off and landing procedures for helicopters. Navigation lights and foghorns had to be passed by the Norwegian Coastal Directorate, the Norwegian Maritime Directorate was responsible for lifesaving equipment, the Norwegian Pollution Control Authority inspected treatment facilities for everything due to be discharged to the sea, and the Norwegian Telecommunications Directorate approved communications installations – including the emergency radio.

Final approval was given once it was confirmed that all safety requirements had been fulfilled. The NPD itself checked compliance with the working environment regulations as well as the functioning of the metering instruments which would guarantee that the government received its rightful share of the revenues.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Norges Handels og Sjøfartstidende. (1979). 12 November. Oljedirektoratet sier JA til produksjonsstart.

Start-up

Production started from four wells in the southern shaft on Statfjord A. One had an external sand filter, while the others were completed by perforation – in other words, holes were shot into the formation through the casing. The latter is a tube cemented into place over the full length of the well. Production tubing was run inside the casing from the rock formation to the platform topside in order to bring up the wellstream.

Driven by the high pressure of no less than 350 atmospheres in the reservoir formation, oil and gas flowed through the perforations, into the well and up the production tubing. Some distance beneath the seabed, this wellstream passed through a downhole safety valve which could be opened and closed from the topside.

On the cellar deck, the flow passed through two main safety valves incorporated – along with a number of other valves – in an array known as a Xmas tree. The external shape of this arrangement can indeed call to mind a surrealistic Christmas tree on a massive scale. The next obstacle for the wellstream was the choke valve. Its opening could be regulated to control the flow and thereby determine the volume of production.

The wellstream then passed into separators, where gas and water were removed from the oil. As it passed through a series of separator stages, the pressure of the crude was gradually reduced until it reached one atmosphere and could finally flow under its own weight into the big storage tanks in the concrete gravity base structure (GBS).

Most of the gas was burnt off through the big flare boom during the first few months, but some was used as fuel for the turbines driving large generators to provide power for the platform. The gas was later injected back into the reservoir.

The whole production process was run from the control room, where Jan Henry Larsen was working on the day Statfjord A came on stream. “This went smoothly, everything was fine,” he recalls. “A ribbon was cut, and coffee and cakes were served, but that was the extent of the celebrations.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Jan Henry Larsen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 30 September 2010.

This event marked the start of a new life for the control room personnel. In addition to all their other jobs, such as monitoring the process and the alarms and signing work orders, they now had to begin calculating production volumes and sending telexes to land. To start with, they only had a small hand-held Casio calculator and spent hours on carrying out extensive computations.

As soon as midnight arrived, the volume had to be calculated with shrinkage factors – differences in pressure and temperature – before the papers were delivered to the radio shack. All the data were then punched onto tape for feeding into the telex and transmission to land, ready for the morning meeting there.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Interview with Jan Henry Larsen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 30 September 2010.

Offshore loading

The oil could not be left in the storage tanks. It had to be exported by shuttle tanker to refineries in various parts of Europe. Equipment to transfer the crude from platform to tanker had not been properly tested in advance, because a realistic trial would have required both oil and ship – neither of which were available until production had begun. So testing took place with the first cargo.

Four large cargo pumps down in the utility shaft pumped oil via metering stations to the loading buoy and into the tanker. A lot of adjustment was needed. The pumps had to be tuned to provide the correct pressure and volume, and checks carried out with the metering stations, flowline and all the other equipment involved. It was a complex system.

Jim Gafken, an idiosyncratic American who had arrived on Statfjord A to assist during the start-up and loading processes, took part in transferring the first consignment. He was down in the shaft beside the pumps. Einar Jensen, responsible for the start-up on behalf of Mobil, was in the control room to monitor the operation. People were otherwise stationed everywhere – in the processing facilities, on the loading buoy, on the tanker, on deck and so on.

Three pumps in all were to be set in motion. The first was started up and the valves opened, and the tanker soon reported that it was receiving liquid ¬– initially just water which had accumulated in the system, and then crude. Everything seemed to working fine.

When the second pump was activated, however, the system began to become unstable and pressure variations arose. These caused powerful vibrations in the flowlines which ran through the utility shaft, through its wall and along the seabed to the loading buoy. The pipes shook.

Jensen rushed out of the control room to see what was happening. “A lorry tipping rocks down into that piping couldn’t have made more noise,” he says. The only option was to shut down.

It transpired that the instability was due to a control valve which was not functioning as it should. Once that had been adjusted, the equipment was started up again. Jensen recalls what happened next:

“Gafken phoned the control room from down in the shaft and asked ‘What’s happening, man?’. I said that things were going fine, I thought we had it under control. ‘No, we don’t have control, because either me or the pump is coming up,’ Gafken said. It turned out that the pump was hopping up and down at the bottom of the shaft. There was a fault in the tanker at the other end.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Einar Jensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 14 June 2010.

They carried on in the same way for almost 80 hours before the vessel had been loaded. Transferring oil to a tanker proved a demanding operation. The storage cells always had to contain liquid, and the large volumes of oil being transferred had to be replaced by water. So as the crude sluiced out, seawater sluiced in.

That was another system which had not been tested in advance, and the sound it made when starting up was like a train rushing over the deck. The process operators were very uncertain whether they had this under control. Nobody had heard that noise from the facility before.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Einar Jensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 14 June 2010.

It was also wet and windy during the first loading operation. The shuttle tanker had arrived on 4 December, but a strong gale gusting to storm strength had blown up during the afternoon.

Conditions had deteriorated by midnight into a heavy storm gusting to hurricane strength, and the biggest waves were 16-25 metres high. The tanker pitched and rolled violently, but was nevertheless filled with the first consignment of 100 000 barrels from Statfjord.[REMOVE]

Fotnote: Lindøe, J., & Stavanger sjøfartsmuseum. (2009). Inn fra havet : Bøyelasternes historie. Stavanger: Wigestrand ; Stavanger sjøfartsmuseum: 39.

Panic reset

It was a big day on Statfjord A when the first cargo was to be pumped aboard the tanker, and the operations manager was affected by the gravity of the occasion. Nobody else was allowed to come near the control console.

On the morning of the great event, the operations manager – who was a nervous type anyway – had become a little stressed. The night before, while he was asleep, two new buttons had been installed on the control panel for the sole purpose of playing a practical joke on him. They blended well with the other buttons and switches, and were labelled Panic and Panic reset.

When he appeared in the control room, his first action was to go straight to the panel and check it. He noticed nothing unusual and relaxed in the chair in front of the consol. Apparently accidentally, one of the technicians pressed the Panic button.

The operations manager screamed “Which button have you pushed?”, and then resolutely pressed the one marked Panic reset. He gave strict instructions to everyone to keep away from the panel. Several days passed before he realised that his leg had been pulled.

From Muntre historier fra Statfjordfeltet (Amusing stories from the Statfjord field) by Einar Torwing.

The tanker

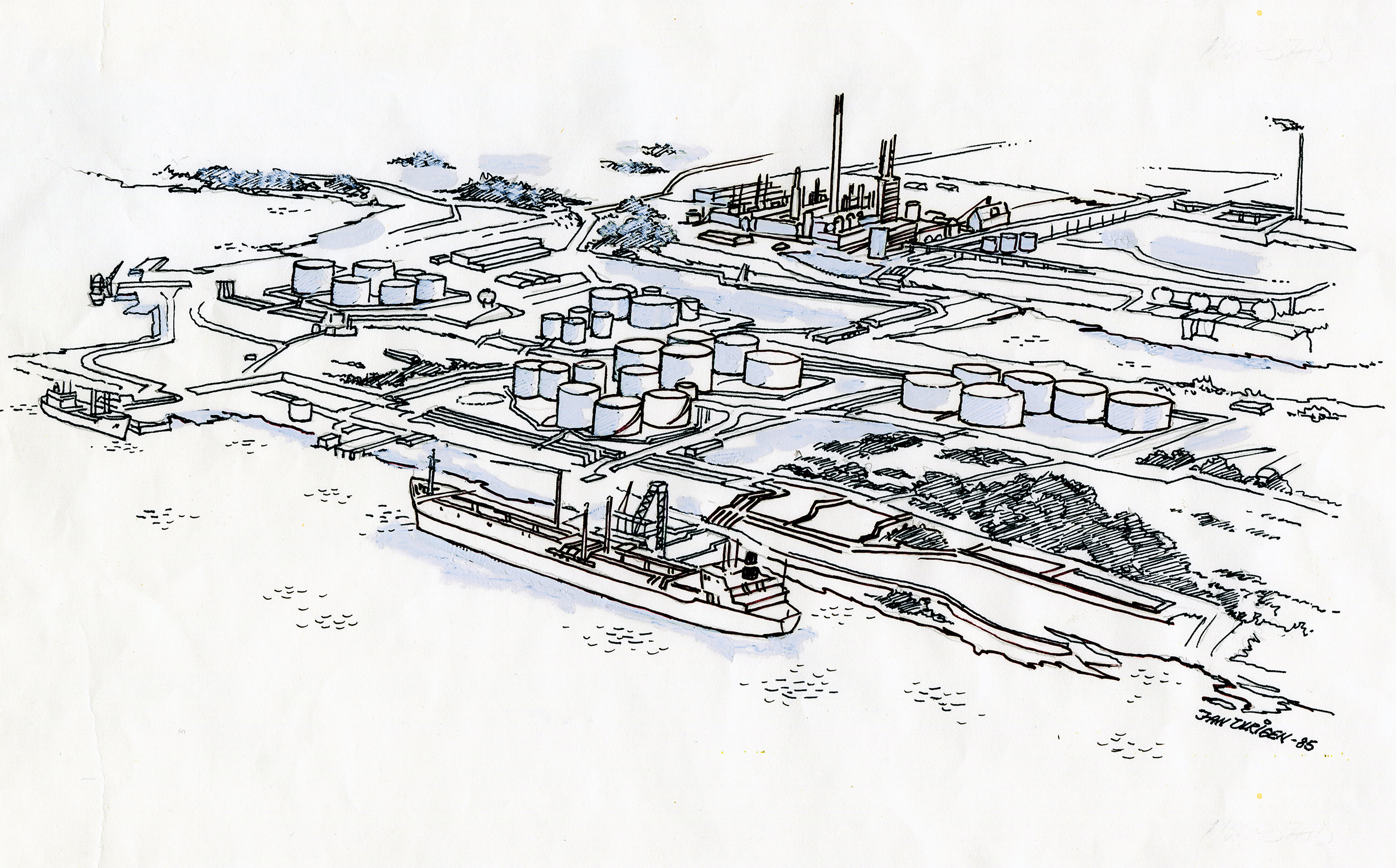

historie, forsidebilde, Første oljelast,

historie, forsidebilde, Første oljelast,The shuttle tanker employed for the first loading operation was called Polytraveller and had been specially designed to load from the Statfjord A buoy. Two powerful bow thrusters and a reversible propeller were invaluable for steering the ship up to the buoy.

It could be manoeuvred from a small bridge right up in the bows, where equipment was also installed to connect the loading hose for oil to be pumped aboard. Since the top of the loading buoy rotated, the tanker could lie bows-on to wind and weather at all times.

To moor the tanker to the buoy, a pick-up line had to be taken aboard in order to haul in the actual hawser. An auxiliary vessel helped to secure this line for the first loading operation, but the tanker could have fished it up directly without problems – which was what happened with later loadings.

When the mooring hawser had been pulled out of the buoy, a weight inside the latter was raised and locked in that position. Once loading had been completed and the tanker disconnected, the weight descended and pulled the hawser back into the buoy.

The termination of the loading hose, known as a Y-piece from its shape, was attached to the hawser and pulled on board with the aid of a winch. Once there, it was locked down and pumps on the platform transferred oil from the storage cells through a flowline on the seabed, up the buoy, along the loading hose and into the tanker’s cargo holds.

An essential step during transfer of the oil was to meter the volume being loaded. This was done with the aid of a propeller installed in the flowline. The faster the oil flowed, the faster the propeller turned and the results could be read off in the control room. This metering formed the basis for allocating the oil between the licensees and for calculating taxes.

The metering system had to be calibrated to ensure that it was accurate and working as intended. This was done in part with the aid of a rubber ball inside the flowline, which was pushed along by the oil. Measuring how long it took the ball to pass through the pipe allowed the oil volume to be calculated. The pipe was 20 inches in diameter.

Einar Jensen was involved in this work, and recalls: “We were carrying out a calibration when something or the other went wrong. The rubber ball disintegrated in the pipeline. What do we do now, we asked ourselves? We had to get out all the bits somehow or the other and clean the flowline.

“I said we had better go and eat, and think about the problem. When we returned after lunch, a member of the crew had already put on oilskins and a breathing apparatus, gone into the flowline and removed all the pieces. We reassembled the ball, and ensured that all the bits had been recovered. This wasn’t exactly in accordance with procedures, but it showed initiative.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Einar Jensen by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 14 June 2010. All the same, Jensen – as Mobil’s supervisor – was not especially pleased that one of the crew, even if he was a very experienced man with many years of service on tankers, had taken that kind of initiative on his own account.

Transport company

The K/S Statfjord Transport a.s & Co limited partnership was responsible for transporting oil from the field. Operated by Statoil, it was owned by the licensees with the same proportionate interest they had in Statfjord.

This company had joined forces with Norwegian engineering company Pusnes Mekankiske Verksted and shipowner Einar Rasmussen Rederi to develop a tailormade system for loading oil in the open sea under fairly rough weather conditions.

Offshore loading was not an unknown technique – it had been used during early production from Norway’s Ekofisk field, for instance. But the new solution was the most advanced of its kind.

The shuttle tankers using it were the first in the world to meet international standards for pollution prevention, recommended by the Inter-Governmental Maritime Consultative Organisation (Imco) in a 1973 convention.

The hawser which moored the tanker to the loading buoy could cope with 500 tonnes of bollard pull. If it nevertheless broke, the loading valves would shut down within a maximum of 27 seconds. Not a lot of oil could escape in that time.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Avisen. (1979). 14 December. Skreddersydd innlastingssystem. og Bergens Avisen. (1979). 14 December. Første lasten verd hundre millioner…!

In addition, the tankers had segregated ballast tanks, making it unnecessary to carry seawater in the oil tanks on the voyage out to the field. That in turn meant that polluted water did not have to be pumped to the sea before loading began.

Although the procedure had not been tested in the North Sea before the first consignment was loaded, everyone involved had been on training courses. These drilled them in the loading method with the aid of boats in a model tank under realistic wind and wave conditions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Avisen. (1979). 14 December. Skreddersydd innlastingssystem. og Bergens Avisen. (1979). 14 December. Første lasten verd hundre millioner…!

Arrival at Mongstad

historie, forsidebilde, Overskridelser og lederskifte

historie, forsidebilde, Overskridelser og lederskifteStatfjord’s first oil cargo reached the Rafinor refinery at Mongstad north of Bergen on 13 December 1979. Loading had been quicker than expected, and the planned celebration at Mongstad – due to be attended by the NPD and petroleum and energy minister Bjartmar Gjerde, among others – had to be cancelled. The oil arrived a day early.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bergens Avisen. (1979). 14 December. Skreddersydd innlastingssystem. og Bergens Avisen. (1979). 14 December. Første lasten verd hundre millioner…!

The oil was distributed among the licensees in proportion to their holding in the field, and the company receiving crude was responsible for selling it. Statoil and Raffinor took the first consignment. The second was received jointly by Conoco and UK state oil company British National Oil Corporation (BNOC),[REMOVE]Fotnote: BNOC became Britoil in 1982 and was acquired by BP in 1988. and shipped in M/T Polytrader to Conoco’s Immingham refinery in north-east England. The third consignment again went to Statoil and Raffinor.

Loading equipment on the field was really put to the test during the second operation. After Polytrader arrived on 20 December, only a few tonnes had been loaded when it had to disconnect from the buoy because of a technical breakdown on Statfjord A. Loading began again on the morning of 23 December, but again had to be halted because no helicopter was available for the personnel on the buoy.

forsidebilde, Oljeutslipp fra Statfjord A, Polytrader sjøsatt

forsidebilde, Oljeutslipp fra Statfjord A, Polytrader sjøsattThe tanker again disconnected from the buoy and sailed around the field while awaiting a new helicopter. This finally arrived on 25 December, but the weather had then worsened. A strong gale was blowing, with significant wave heights of 5.2 metres. The highest waves were no less than 10 metres – around the upper limit set for oil loading. After the tanker had connected on, however, the operation proceeded without problems and demonstrated that loading could be carried out in bad weather.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Status. (190\80). no 1. Lastingen på Statfjord i full gang.

Union officials resignSick pay scheme